Interference: An Option or A Necessity?

Article By Pierre Poulain

As a street photographer I have the opportunity to travel worldwide, to present exhibitions, to present various photography workshops, and of course to take new photographs.

As a street photographer I have the opportunity to travel worldwide, to present exhibitions, to present various photography workshops, and of course to take new photographs.

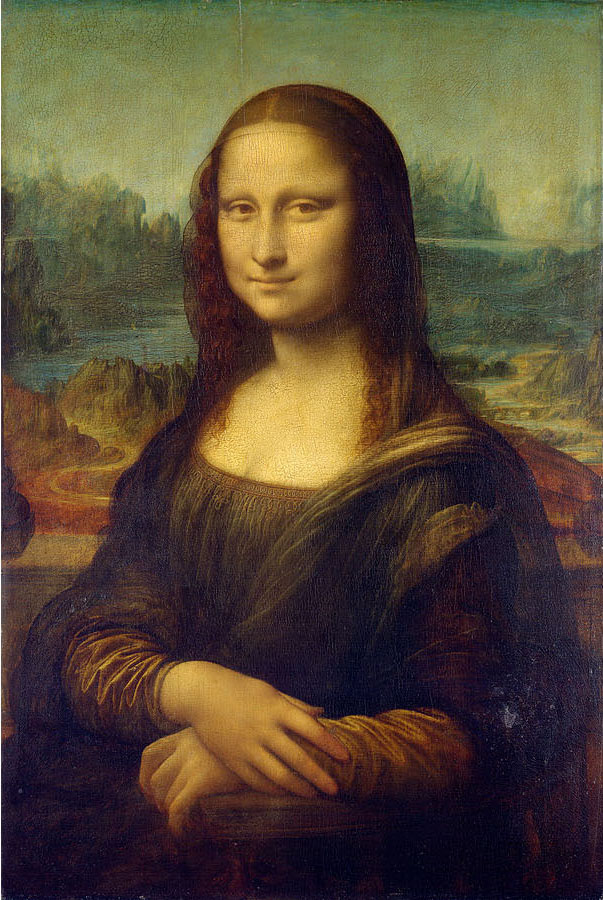

From those travels there is a photograph I have always presented in my last few workshops. I use it to illustrate a “dynamic composition”, which is a composition with a lot of visual elements, allowing a dynamic lecture of the photograph. This particular photograph is not an outstanding example of such a composition, but I use it to explain an ethical concept, and to initiate a dialog with the workshop participants about whether or not it is necessary for the photographer to be involved in a situation – in this case, it was at a street event. I would like to enlarge this example to our ethical rights and obligations, as human beings…not only as photographers.

The photograph I use to illustrate this article was taken in the summer of 2010 on the banks of the Thames, in London. It shows on the left a couple of gypsy musicians, and some children who might be coming back from school (it was around 14:00, mid day time), deliberately walking over the hat that was used by the musicians to collect money; they were making loud noises, laughing and singing, to disturb the musicians. On the right other people are walking away, indifferent to the event, paying no attention to what had occurred beside them. Well, this may be my interpretation, and looking at the photograph we may consider that the 2 people walking on the right are indeed unaware of the situation. But the photograph must be placed again in its temporal context: about half an hour before, in another part of London, I was walking with a friend – and my camera – and a man, apparently quite drunk, fell to the ground about 10 meters from me. Instinctively I approached him to see if he needed any help. My British friend stopped me and told me not to touch him; not to interfere, that it was his right to be drunk and fall…

Of course I did approach him (but I did not touch him), talked to him, and as he regained consciousness and claimed he did not want any help, I left him after a few minutes. But I did not forget the remark of my friend. When I saw, later the same day, the scene with the musicians, I vividly recalled the previous situation with the drunk guy and a question awoke in my mind: Is there a limit to the right amount of interference toward individuals? Is it right never to interfere? Must we always interfere? Or are there criteria we could use to know when we should not interfere, when we may interfere or when we must interfere?

The first thing to consider is that using criteria consciously – not mechanically – is never the easiest solution, but it may be the most human one; the best, and from a philosophical aspect, the only one. It is always easier to hide ourselves behind “iron rules” and declare that in no circumstances, may we break the rules. This may apply to the rule “never to interfere” or the contrary, “always interfere”.

The first proposition leads to a grotesque caricature of the “British phlegm” and to the justification of the non-interference, which in reality is a poor excuse for avoiding natural human relationships with other people. It maintains the unnatural separation that people are experiencing in modern life, especially in large urban towns. In those cities everyone is living with thousands of souls around, a non-stop noise, but one may feel even more alone than if he was living in a little house, in the country, surrounded by trees and with the closest neighbor living some kilometers away. To survive, some wear a psychological and mental armor which isolate them from people around, and because they consider this isolation as protection, they will do anything to maintain it; including finding a moral justification for the isolation.

But let us remember what is said, for example, in Buddhist philosophy; the “illusion of separation” is the worst of all illusions. It is said to be an illusion because it is not True. This does not mean that separation and isolation do not exist. Obviously they do: we experience them. It means that the attitude of separation is not Just – as Justice and Truth are, from a philosophical perspective, different expressions of the same archetypal concept. It is not Just because it is not True, and it is not True because it does not correspond to a natural human ethical need. We may fall into the trap to think we may survive better if we separate from other human beings, but this will only reinforce the Ego in all its negative aspects: egoism and egocentricism. We may survive…but the price we will pay is the sacrifice of some the most important human values: generosity and empathy for others, the ability to consider oneself as part of Humanity, and hence to relate to other human beings as brothers and sisters. As I said, we may survive…but not live.

The second proposition, the opposite one, is not better: it is to consider that we always have the right, and even more, the necessity, the obligation, to interfere in other peoples’ lives – to “adjust” it and correct it according to what seems just and good to us. It is to consider that the differences should be canceled, that if something is good for us, then it must be good for all and thus it is our moral obligation to “show the Truth”. This conception leads usually to a missionary attitude, whether in the field of religious or ideological understanding. It emphasizes a fanatical way of considering other human beings, other cultures, and in general perceives human differences as wrong, and gives an apparent moral justification to an arbitrary reduction of all the differences. This is the justification used by all dictators and tyrannies, when they explain that they have to “educate” – or “re-educate” – the people “for their own good”, or when they are not just trying to eliminate them brutally as it is occurring now in Syria, and when at the same time most of the Occidental countries are hiding under the justification of non-interference. (Well, they talk…but they don’t act).

The only human attitude resides – as always in philosophy – in the middle. Not in the extremes. This means that sometimes we shall have to interfere in a situation, and sometimes not. It means that there is no easy answer written in advance which could apply to any situation. It means that every decision has to be taken consciously, and that we are responsible for our decisions and actions. We have to consider at every moment the situation in entirety. As philosophers, we have to consider not only religious, political or economical factors, but must first consider the human factor, and… THINK. Think and feel. Open our intelligence and our sentiments, and become able, in any place, and at any moment, to determine what is JUST and what is RIGHT.

In general, it will not be easy. Nor will it be the most widely recognized or understood attitude. Sadly, the Just and the True, just like the Beautiful and the Good, are not always present in the seeds of our societies; but they are in the human heart and in its spirit. The ability to recognize them and to act according to these eternal values makes us what we really are: just humans – A dynamic bridge between the separation and the reduction of the differences. And this makes us the Guardians of these Differences, being able to respect them without judging them. Between the attitudes consisting of falling into the trap of isolation at any price, and the opposite consisting of reducing by force all the differences, there is a wide space for humanity: this is the place for every philosopher, for every lover of wisdom, for every real human being to conquer. This is a place for a better life, and this place is in our heart: it waits for us to discover it.

Image Credits: By Leticia Bertin | Flickr | CC BY 2.0

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By Leticia Bertin | Flickr | CC BY 2.0

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

Article References

Pierre Poulain is the founder of New Acropolis in Israel, and was its National Director until 2016. Today he is the Coordinator of Countries for the regions including Asia, Africa, and Oceania.

What do you think?