Nicholas of Cusa

Article By Anonymous

Nicholas Cryfts – or Krebs – was born in Kues (Cusa), on the banks of the River Moselle, in the region of Trier, now Germany, in 1401. His father, Johan Cryfts, a rich ship owner, died in 1451 and his mother, Catherina Roemer, in 1427.

Nicholas Cryfts – or Krebs – was born in Kues (Cusa), on the banks of the River Moselle, in the region of Trier, now Germany, in 1401. His father, Johan Cryfts, a rich ship owner, died in 1451 and his mother, Catherina Roemer, in 1427.

His early education took place at the school of the Brothers of the Common Life, in Deventer (Netherlands), whose devotio moderna, combining mysticism and reason, had a powerful influence on the young student. He first studied law at Heidelberg and Padua, becoming an expert in Canon Law. During his stay in Padua he struck up a friendship with Paolo Toscanelli, a renowned doctor and scientist. After several years of legal practice, he studied Theology at Cologne and was ordained a priest. He also studied Latin, Greek, Hebrew and later Arabic.

1432 saw the beginning of his political and diplomatic career, when he attended the Council of Basel as his bishop’s representative, with the mission of achieving the reform of the calendar and fostering the political and religious unity of Christendom. In 1437 he entered the service of Pope Eugenius IV, who sent him as papal legate to Constantinople to prepare the coming Council of Ferrara and ensure the attendance of the Emperor John Palaeologus, the Patriarch of Constantinople and a numerous group of bishops; this with a view to the unification of the Catholic and Orthodox churches, which was briefly achieved. A member of that delegation was George Gemistus Plethon, who was responsible for the Neoplatonic direction of the Florentine Academy. During his brief two-month stay in the capital of the Byzantine Empire, he discovered Greek manuscripts by St. Basil and St. John Damascene. In 1438 he was back in Ferrara reporting to the Pope and later taking an active part in the Council of Florence.

In the years that followed, he was extremely active as a papal envoy to various German Diets, preached the crusade against the Turks, reformed churches, monasteries and hospitals and tried to get the Hussite heretics to return to the bosom of the Church. At the same time he undertook delicate political missions at the highest levels, such as the pacification of relations between England and France. As the alchemist Abbot Trithemius would say of him: “everywhere he appeared as an angel of light and peace”.

In 1448 the pope appointed him cardinal and, although he refused this honour, he was forced to accept by the following pope, Nicholas V, who assigned him to the church of St. Peter Ad Vincula in Rome and sent him to the diocese of Brixen. On taking charge of this mission he became involved in political conflicts with Sigismund, the Duke of Austria and Count of Tyrol, who imprisoned him and forced the Cusan to resign, resulting in his papal excommunication.

In spite of his pacifying character and of having resolved so many disputes in the course of his life, he was unable to see peace in his own diocese, which occurred two years after his death. This took place in 1464 in Todi, Umbria, while he was carrying out another mission as an envoy of Pope Pius II. His body lies in his church of St. Peter Ad Vincula in Rome, but his heart was deposited in front of the altar of the hospital of Cusa. This had been founded by the cardinal using his family inheritance and was the recipient of his important library and scientific materials. Deventer, the city where he had studied in his youth, also received the “Bursa cusana”, an endowment to fund the studies of poor young seminarists.

His Works

His extremely active life did not prevent him from producing a large volume of work, which can be classified into four sections:

- Legal writings: “De concordantia catholica” and “De auctoritate praesidendi in concilio generali”, for the Council of Basel, in which he upheld the superiority of the Councils over the authority of the Pope and proposed reforms which were implemented some time later.

- Philosophical writings: the most well-known of these is his treatise “De docta ignorantia”, on the finite and the infinite. He sets out a Theory of Knowledge in his treatises “De conjecturis” and the “Compendium”.

- Theological writings: these are dogmatic, ascetic and mystical treatises, in which echoes of Thomas Kempis are to be found. “De cribratione alchorani” written on the occasion of his visit to Constantinople, deals with the subject of the conversion of Muslims. “De quaerendo Deum”, “De filiatione Dei”, “De visione Dei” and “Excitationum libri X” contain his reflections of a mystical character concerning the Holy Trinity and the notion of God and his relations with the world.

- Scientific writings: these are contained in twelve treatises, most of them short, including “Reparatio calendarii”, a correction and updating of the Alfonsine Tables, drawn up in the times of Alfonso X the Wise. In his works on mathematics he discusses the squaring of the circle and frequently uses the symbolism of letters and numbers in his reflections. As regards Astronomy, for the Cusan the earth is not the centre of the universe, neither is unmoving, but in motion; its poles are not fixed and the heavenly bodies are not completely spherical, neither are their orbits circular.

The Thought of Nicholas of Cusa

Nicholas of Cusa is regarded as the precursor of the new philosophy of the Renaissance, referred to as “modern” or pre-modern. Giordano Bruno was regarded as the disciple and follower of the Cusan cardinal.

He took up again the idea of cosmogonic evolution, in which God, instead of the unmoving and all-perfect mover of Scholasticism, is based on movement, which he also uses for his relations with the world.

The world is divine evolution, which makes it more important.

Finally, man reveals traces of God and of movement in the essence of his cognitive capacity. These elements, the value of the world and of man, became essential parts of the Renaissance philosophy which later made its appearance.

As for his Theory of Knowledge, he distinguishes four levels: the senses, which provide confused and incoherent images; the reason, which diversifies and orders them; intellect, the speculative reason which unifies them; and finally, intuitive contemplation, which enables one to comprehend the unity of opposites.

We can summarise the philosophical propositions found in his works as follows:

- Doctrine of conjectures. Truth is beyond our knowledge, and the knowledge that this is the case is the first science. This is the idea of “docta ignorantia”, that is to say, wisdom as a recognition of the limits of knowledge. He takes from Pseudo Dionysius his negative theology and the path to the Deus absconditus: in order to aspire to the knowledge of the supreme unity it is necessary for man to do away with positive affirmations, letting go of the knowledge of opposites.

- Doctrine of the “coincidentia oppositorum”. God – because he is infinite – is beyond what is and what is not, and in Him are found both these dimensions and all the oppositions that arise among beings. He is the supreme unity, requiring the soul to enter into a state of intuitive contemplation, beyond knowledge, which leads him to the knowledge of God.

- Doctrine of the “posset”. All that exists is possible. Possibility should be prior and subsequent to being in act. In God both exist. God is neither mere being nor mere potential to be, but “posset”, that is, potential to be which has come into being in a real and absolute way.

- Doctrine of complication and explication. Since everything is possible in God, he is the complication of all things, therefore the difference between God and the world is only relative. God with respect to the world does not have more being, but has it in another mode. The world is a manifestation of God and therein lies the principle of its unity and order; it is the ‚”maximum specific and compound”.

In his work we can see precedents of Giordano Bruno’s idea about the infinite, symbolised in the phrase “God is a sphere whose centre is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere”, a statement which already existed in a Hermetic treatise of the 12th Century entitled “Liber XXIV philosophorum” by Clemens Bacumker.

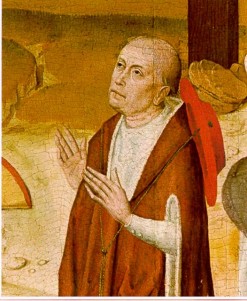

Image Credits: By Master of the Life of the Virgin | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By Master of the Life of the Virgin | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

What do you think?