Rediscovering the Hieratic Dimension in Art

Article By Siobhan Farrar

Both the National Gallery in London and the Louvre in Paris have shown major exhibitions this year on 13th century art with its sense of the hieratic or ‘sacred’ dimension in art. With two major European institutions choosing this focus, what might it have to say about our current times and aspirations?

Both the National Gallery in London and the Louvre in Paris have shown major exhibitions this year on 13th century art with its sense of the hieratic or ‘sacred’ dimension in art. With two major European institutions choosing this focus, what might it have to say about our current times and aspirations?

13th century Europe saw the rising spires of gothic cathedrals and great advancements in art and culture, it was a time of civilizational ascendancy that led ultimately to the Renaissance. At this moment, the church was the seat of civilizational power and all cultural and social forms were mediated through her. This is not to suggest that the hieratic or sacred dimension is the sole province of Christianity or any other religion, but that this was simply the expression of the time.

The hieratic or ‘sacred’ dimension reflects the sense of art as a pathway to spiritual elevation and the ‘revealing of a mystery’. When, separated by time’s oceans, we stand in front of a painting and witness some hidden presence of Life, its timeless truth, glory and beauty, and experience how it can move us deeply… it is something extraordinary and we wonder what has happened to us.

For the artists of the 13th century, intelligible Beauty was a moral and psychological reality. These things weren’t considered relative to individual taste but – in line with Platonic philosophy (which inspired much of Christian theology) – intelligible, aesthetic and moral truths existed. The artist sought to make contact with these realities and transmit them. It is important to understand that art with a sacred dimension is not a chance occurrence or a random gestural accident. Rather, through a dynamic obedience (the word ‘obedience’ has the root meaning ‘to listen’ or ‘to perceive’) the artist seeks contemplation of that which IS, encountering the fire of divine mystery with its awe and holy silence… (McColman, 2023).

“The drama of the aesthetic discipline lies precisely in a tension between the call of earthbound pleasure and a striving after the supernatural… Furthermore when this discipline is victorious it brings peace and mastery over the sensual” (Eco, 1986).

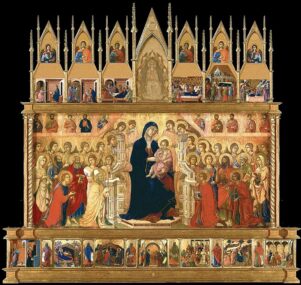

The medieval city of Siena was an important place of sacred art, situated on the Via Francigena pilgrimage route between Canterbury and Rome. The proximity of cities to the Via Francigena supported their prosperity, as did being in reach of the ‘silk routes’, which meant that artists could take inspiration from the Byzantine world as well as from across Europe. The Sienese style was highly experimental, innovative and sacred. Duccio’s Maestà altarpiece made for the cathedral of Siena demonstrated possibilities of narrative storytelling in paint on a scale not attempted since. In a later Maestà painted for the Palazzo Pubblico, Simone Martini was able to express an entirely new subtlety of emotion and his depictions of the Archangel Gabriel are as exquisite as anything ever created by the human hand. With their innovation they also preserved the possibility of transcendence and created works that are original expressions of something timeless, that can hold open a space and the possibility of stepping into some deeper truths. “In Sienese art, symbolism is not decoration, but revelation” (Schuon, 2007).

By comparison, earlier medieval centuries produced art that was quite flat, formalistic and cartoonish. A passive acceptance of prevailing dogmas always thwarts innovation and individual creativity. The dogmas of those early centuries were religious, but today we have our own and our art forms can be no less dull and lifeless than some dreary medieval tableau…Today, it is the dogma of materialism that is most pernicious, denying as it does the possibility of the transcendent realities which meant so much to the Sienese masters.

Whenever we see times of important civilizational progress, such as happened in the 13th century, we also find a spirit of confidence and certainty about the future. Why build (or even imagine) a cathedral, pyramid or beautiful image of the Madonna, if life is understood as more or less transactional, relative and without meaning? Artists have always struggled with circumstance, doubt and limitations, but some have been able to transcend this and transmit a vision beyond the confines of their own lifetime. A message from the heart cast across death’s abyss to future worlds that will and must exist…

Times of great civilizational activity occur at two moments, when cultures are either being born or when they are dying. The activity of a dying culture is characterized by dissolution, fragmentation and separation, much like the physical body in the process of death. Whereas the activity of civilizational birth is characterized by a coming together, integration and expansion. In the Neoplatonic tradition, unity at any level is the result of a higher principle, because unity occurs under the guidance of something that can harmonize the parts. The creative outpouring of the 13th century was harmonized through the timeless dimension where intelligible Beauty resides.

“Sometimes we find the greatest value, meaning and purpose in life not by chasing after the new but by allowing something venerable and old to form and nurture us” (Rabbi Kaplan citied in Colman, 2023).

The intention to seek higher truth – whether moral, aesthetic or divine – is also an attitude towards life, with the natural sense of it heading somewhere. Materialistic dogma not only denies the realm of intelligible Beauty, but in the extreme it denies the future too. If nothing gives cohesion, we are left with nothing to hold us together and no way to build. Let us rediscover a sacred dimension in art with curiosity about the existence of transcendent realities, about our creative possibilities and with obedient listening to the beating heart of life.

“All the way to heaven is heaven” – Catherine of Siena

Image Credits: By Web Gallery of Art | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By Web Gallery of Art | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

Article References

Eco, Umberto (1986) Art and Beauty in the Middle Ages. London: Yale University Press. Schuon, F. (2007) Art from the Sacred to the Profane. Indiana: Word Wisdom, Inc. McColman, C. (2023) The New Big Book of Christian Mysticism. Minneapolis: Broadleaf books. Llewellyn, Laura. Painting’s Golden Moment. Art Quarterly, Spring 2025.

What do you think?