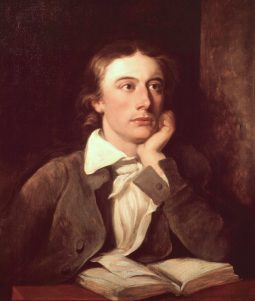

John Keats: Immortal Beauty

Article By Maria Virginia Reina

“A thing of beauty is a joy forever. Its loveliness increases; it will never pass into nothingness”

“A thing of beauty is a joy forever. Its loveliness increases; it will never pass into nothingness”

So begins the epic poem Endymion by John Keats. And in these opening lines, as through his exquisite body of work, he presents to us one of the core themes of his poetry, if not all art: that the archetype of Beauty is immortal.

Keats knew death intimately. By the age of fourteen he had lost his father, baby brother and his mother. As the eldest remaining male in the family, he left education and became a surgeon’s apprentice. At eighteen he enrolled at Guy’s Hospital in London to train as a surgeon and apothecary, where mortality would have continued to be the inevitable and constant truth.

But he soon renounced his medical career in pursuit of poetry. Over the next five years of his life he wrote some of the most sublime and enduring poems of the English language, as well as suffering another death – that of his brother Tom, from consumption. Perhaps through poetry he sought out an alternative Truth; in Endymion he explored the immortality of the soul.

Keats knew his own death was imminent. On the 3rd of February 1820, after suffering a fevered fit of coughing, Keats held a candle to a single drop of blood on the sheets, and said calmly:

“That is blood from my mouth. […]

I know the colour of that blood; – it is arterial blood; I cannot be deceived in that colour – that drop of blood is my death warrant – I must die.”

Keats died penniless aged only twenty-five, in the Eternal City of Rome, the climate of which his faithful friends had hoped would alleviate the tuberculosis.

But in his short life, Keats experienced love and beauty as closely as he had sickness and death, and perhaps it is this understanding of duality that moved him to write as he did.

In the poem “Ode to a Nightingale”, perhaps his most famous, he lies beneath a tree and listens to the birdsong in an almost dreamlike state. “Embalmed in darkness”, he is reminded of the ecstasy and pleasures of life, and in his exclaiming “Thou art not born for death, immortal Bird!”, he recognises that the beautiful song existed before him, and would certainly outlive him.

Keats perceived immortal Beauty in Nature, and everywhere, not least of all in art. In “Ode on a Grecian Urn”, he reflects on the figures depicted on the ancient artefact – scenes depicting life, on a vessel intended to carry the ashes of the dead; a vessel that has outlived its maker by millennia.

The subjects of the Urn are forever captured in a single moment: trees whose leaves are never withered by time; lovers always caught in the anticipation before their kiss, their lips never meeting; their beauty never fading.

And just as the Urn is a vessel, so Keats believed poets themselves to be vessels of Beauty – “chameleon” beings with “no identity […] filling some other body, the Sun, the Moon, the Sea,”[1] and also possessing the trait of Negative Capability: “that is when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason”.[2]

For Keats, the search for Truth through poetry meant embracing the unknown and relishing its endlessness. As he concludes in “Ode on a Grecian Urn”:

“Beauty is Truth, and Truth Beauty.

That is all ye know on Earth,

And all ye need to know.”

Image Credits: By National Portrait Gallery: | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By National Portrait Gallery: | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

Article References

1. Motion, A. (1997). Keats. Page 169. Faber & Faber Limited. 2. Brown, C. (1820). Letter cited in: Keats, J. & Barnard, J. (ed.) (2004). Selected Letters. Page 490. Penguin Classics.

What do you think?