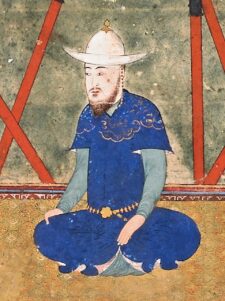

Ulugh Beg of Samarkand

Article By Nataliya Petlevych

In the heart of Central Asia where fertile valleys meet ancient arteries of the Silk Road, lies Samarkand, an enchanting city steeped in legend, adorned with splendid architecture, storied past, vibrant bazaars and serene moments of contemplation beneath a starlit sky. Among its many historical chapters, one shines with particular brilliance – a luminous revival of Samarkand’s might, guided by a ruler whose devotion to science not only transformed his city, but also enriched the course of human knowledge.

In the heart of Central Asia where fertile valleys meet ancient arteries of the Silk Road, lies Samarkand, an enchanting city steeped in legend, adorned with splendid architecture, storied past, vibrant bazaars and serene moments of contemplation beneath a starlit sky. Among its many historical chapters, one shines with particular brilliance – a luminous revival of Samarkand’s might, guided by a ruler whose devotion to science not only transformed his city, but also enriched the course of human knowledge.

Mirzo Ulugh Beg, grandson of the famed conqueror Amir Timur – known in the West as Tamerlane – was no ordinary ruler. Rather than pursuing glory on the battlefield, he dedicated himself passionately to the cultivation of knowledge. His approach to governance was rooted in scholarship, education and cultural advancement. In an age still ruled by the sword, he gathered scholars, poets and artists, built institutions and transformed his court into a centre of learning that would inspire future generations.

From the very beginning, Ulugh Beg seemed to have a special destiny. Born in 1394 in the city of Sultaniyya during one of his grandfather’s campaigns, his arrival was greeted with joy – according to legend, the citadel of Mardin and its inhabitants were granted mercy in honour of his birth. He was named Muhammad Taraghay, but from an early age was called Ulugh Beg, meaning “Great Ruler” – a title that would follow him throughout his life. As the beloved grandson of Tamerlane, he accompanied the conqueror on long and formative expeditions. These journeys exposed him to the diversity of cultures and ideas across the vast Timurid empire. Recognizing his potential, Ulugh Beg’s family ensured he was educated by the finest scholars of the realm. Proficient in Arabic, Persian and Turkic, he built a strong foundation in mathematics, astronomy, philosophy, theology and poetry that would shape his future.

In 1409, at just fifteen, Ulugh Beg was appointed governor of Samarkand. By 1411, he was acknowledged as the ruler of Transoxiana, also known as Mavarannahr – a vast region encompassing modern Uzbekistan, southern Kazakhstan, and parts of Tajikistan and Turkmenistan. He acted under the authority of his father Shah Rukh, the head of the Timurid Empire, supporting him in securing borders and quelling internal uprisings. After a defeat by Uzbek forces in 1427, Ulugh Beg’s engagement in military affairs decreased and he could focus more on his intellectual and cultural endeavours. When Shah Rukh died in 1447, Ulugh Beg ascended as the head of the Timurid Empire for about two years until his untimely death, marking a forty-year span of influence and leadership.

Samarkand already had a strong intellectual tradition, but Ulugh Beg elevated it to new heights by institutionalizing education and ensuring the participation of some of the finest scholars of the Islamic world. He recruited prominent scientists such as Qadi Zada al-Rumi, Jamshid al-Kashi and later Ali Qushji to teach and collaborate at the madrasa and observatory he built. He not only welcomed scientists to the city, but it also became a magnet for poets, artisans, architects and musicians.

Ulugh Beg commissioned magnificent madrasas in Samarkand (1417-1420), Bukhara (1417) and Gijduvan (1433), all of which remained active till the early 20th century. The education there was characterized by a dual focus, encompassing both traditional Islamic theological studies and a strong emphasis on scientific and philosophical disciplines. The entrance to the Bukhara madrasa is adorned by the phrase: “Aspiration to knowledge is the duty of every Muslim man and woman.”

The curriculum of the Samarkand madrasa, described by contemporaries as one of the most respected spiritual universities of the Orient, included algebra, geometry, trigonometry, logic, astronomy, philosophical reasoning, medicine, law, Arabic, Persian, music and poetry, reinforcing the institution’s interdisciplinary scope. What made this madrasa exceptional was its active synergy with the Samarkand Observatory, also founded by Ulugh Beg. Education was not confined to theory but extended into practical research, creating a dynamic learning environment. The students at the madrasa were supported financially: in addition to lodgings and food, they received a stipend during their eight years of studies.

The education Ulugh Beg promoted emphasized vigorous study, critical thinking and open discussion. He taught at the madrasa himself. Contemporary sources, including letters from al-Kashi, describe how he actively participated in scholarly assemblies, often moderating debates or challenging students to defend their positions with logic and evidence. He even tested his students with purposefully flawed arguments to encourage independent thinking and intellectual integrity.

Ulugh Beg also introduced thoughtful economic reforms. In 1428, he initiated a monetary reform that improved regional trade, issuing silver coins with precise weight standards to combat forgery and inflation. He supported caravanserais and urban infrastructure to facilitate economic growth. These efforts created the conditions for Samarkand’s flourishing as a commercial, scientific and cultural capital.

Most notably, Ulugh Beg’s passion for astronomy marked him out as one of the greatest observational astronomers before the modern age. A Timurid poet and statesman, Alisher Navoi, later wrote that “before his eyes, the sky drew near and descended” – a poetic tribute to Ulugh Beg’s astronomical genius.

He personally oversaw the building of the Samarkand Observatory, which was completed around 1429. It was equipped with a massive, precision-built colossal meridian arc, often referred to as a “sextant” or “quadrant”, with a radius spanning over 40 metres. This instrument enabled measurements of celestial bodies with an accuracy astonishing for the time – almost 150 years before the invention of the telescope.

Ulugh Beg and his team embarked on cutting-edge research at the Observatory. They calculated the length of the astronomical year as 365 days, 6 hours, 10 minutes and 8 seconds – deviating by only 58 seconds from today’s accepted value. They also measured the inclination of the ecliptic and the Earth’s axial precession, as well as the annual motion of the planets, with astonishing precision. Ulugh Beg developed one of the first complete trigonometric tables which in particular supported the development of architectural styles and navigational advancements around the world. The Zij-i-Sultani star catalogue created by Ulugh Beg and his team listed over one thousand stars with exceptional accuracy. It became an essential resource for astronomers well beyond Central Asia, influencing scientific developments in Europe, China and India.

Despite his achievements, Ulugh Beg faced opposition from certain conservative factions. His devotion to empirical observation and logical reasoning clashed with traditionalist views. His life came to a tragic end – executed on the orders of his power-hungry elder son in 1449. His observatory was looted by fanatics, ruined and lost to history, to be rediscovered by archaeologists only in the 20th century. His disciple Ali Qushji managed to rescue many books and most importantly the Zij-i-Sultani, and take them to Istanbul. It was a significant event for the Ottoman scientific community, and through his teaching and the spread of the texts from Samarkand’s Observatory, Ulugh Beg’s work became known in other parts of the Islamic world and, eventually, in Europe.

The 15th century historian Davletshah Samarqandi wrote after the death of Ulugh Beg: “Ulugh Beg… was a scholarly, just, powerful and generous ruler. He attained a high degree of learning and profoundly understood the essence of things. During his time, the level of scholarship reached great heights, and worthy individuals occupied important positions under his rule. In geometry, he was akin to Euclid, and in astronomy, to Ptolemy. By the unanimous opinion of the most distinguished and wise individuals, throughout the history of Islam and even earlier, from the times of Alexander the Great to the present day, there has never been a scholar-ruler comparable to Ulugh Beg Gurgan.”

Today, the same sky that Ulugh Beg studied with such devotion stretches over Samarkand’s domes and towers. The Madrasa and Observatory he built – now beautifully restored – and the star maps he left behind, translated into many languages and printed across the world, all stand as enduring reminders of a ruler who transformed Samarkand into beacon of reason, beauty and learning. Together, they remain a testament to the lasting power of wisdom and knowledge over ignorance and destruction.

Image Credits: By Eugene a | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By Eugene a | Wikimedia Commons | CCBY PD

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

What do you think?