A Stoic guide to our Emotions – Pt. 2: The sentiments of the sage

Article By Gilad Sommer

Despite the popular conception of the Stoics, in their writings, the ideal sage is not portrayed as a cold, apathetic person. By reflecting on the good and the bad, and on the true nature of things, the sage develops natural, rational sentiments – Hai Eupatheiai, literally, the good passions.

Despite the popular conception of the Stoics, in their writings, the ideal sage is not portrayed as a cold, apathetic person. By reflecting on the good and the bad, and on the true nature of things, the sage develops natural, rational sentiments – Hai Eupatheiai, literally, the good passions.

These are: Wish, Caution and Joy.

Joy [Chara], the counterpart of pleasure – rational elation.

Caution [Eulabeia], the counterpart of fear – rational avoidance.

Wishing [Boulesis], the counterpart of craving – rational appetite.

Joy [Chara]

If pleasure is caused by an irrational and ignorant perception, rational elation is brought forth by the enjoyment of that which is proper to the human being.

This is the joy of contemplating the ideas, of seeing the beauty of nature, of acting in the light of reason and wisdom.

In our pursuit pleasures, we sometimes lose sight of the beauty all around us.

What can we really pursue that is more beautiful than the blue skies?

Richer than the human being? Deeper and more interesting than our own selves?

In the words of Marcus Aurelius:

“Very little is needed to make a happy life, it is all within yourself”.

Caution (Eulabeia)

Plato defined courage as recognizing what we should be afraid of, and what we shouldn’t be afraid of.

Ideally the philosopher’s rational outlook should allow him to avoid all fear, but if the philosopher should avoid all fear, then where does caution come into the picture?

To avoid unnecessary dangers and hindrances, but above all to avoid the dangers of the soul.

Socrates said that a man should have more fear to cause injustice than to be treated unjustly. The health and purity of the soul are at least as important as that of the body.

The philosopher should use utmost caution to avoid putting his soul at risk, that is, to let his soul sink into the abyss of immorality and impurity. It is a subtle form of caution, but the most rational, as it is occupied with taking care of that which is constant, rational and natural. Having caution in regards to the physical survival of the body, which is temporary in any case, is only second to the spiritual survival of the soul.

This means to know ourselves, to recognize those things, whether external or internal, that drag us down, pollute our soul, make us lose our center, and to avoid these things as much as possible.

The stronger we are inside, the more resistant we can be to negative external influences. But we also need to know our “trial threshold”, as Jorge Livraga called it – to have the humility to know which things are beyond our mastery of ourselves, and are better to avoid completely.

Wishing (Boulesis)

The popular saying “be careful what you wish for” refers to irrational craving – that what we wish for may not always be what is good for us or others.

However, while the philosopher should avoid irrational craving, this shouldn’t be replaced with apathetic, idle, and purposeless living.

Wishing or Boulesis is a rational appetite, it is the pursuit of the things that are truly good, for you and for everybody: the virtues, the excellent completion of your duties, the wish to improve the lives of those around you and on which you are responsible.

The meditations of Marcus Aurelius and the books of Seneca are full of these everyday wishes, who are a constant motivation for improvement and realization.

And this leads us to another question:

Should one’s good life come on the expense of others?

In a highly competitive society like ours, one’s success means another’s failure. If I get a job, another hundred lose it. In a competitive society there are winners and there are losers.

This is the law of the jungle.

It is interesting however that the word compete originates in the Latin competere, which means to strive together.

Will humanity ever establish a society where one’s victory does not mean another’s defeat? Where one’s strength does not mean another’s weakness? Where’s one’s good life does not mean another’s miserable one?

So far, we haven’t been able to achieve that.

Maybe we’ve been wishing for the wrong things?

In the spirit of the Stoics, we can only answer that everything is natural. And as in nature, everything will balance out eventually.

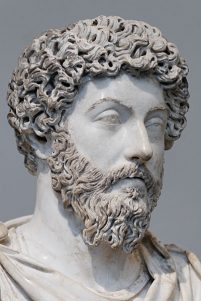

Image Credits: By Marie-Lan Nguyen | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY 2.5

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By Marie-Lan Nguyen | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY 2.5

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

What do you think?