Dionysus – The Mystical and the Heroic

Article By Svetlana Kiruta

“The myths about the god Dionysus tell us about the mysterious connection that exists between the mortal and the immortal in man. He is a symbol of the inner path, the return to the centre, to the throne of Zeus, a symbol of the heroic enthusiasm that inspires a disciple to walk the path, and the mystical insight that gives a vision of this path.”

“The myths about the god Dionysus tell us about the mysterious connection that exists between the mortal and the immortal in man. He is a symbol of the inner path, the return to the centre, to the throne of Zeus, a symbol of the heroic enthusiasm that inspires a disciple to walk the path, and the mystical insight that gives a vision of this path.”

(Antun Musulin, National Director of New Acropolis Ukraine and International Secretary Pythagoras Institute)

It is impossible to touch on certain mythical stories without touching the deepest strings of our souls.

The theogonic myths contain universal elements of the journey of the soul. They warn us about the dangers of this journey: about what enslaves the soul, takes it captive—all our vices, fears and weaknesses. They also tell us what elevates the soul and leads to its liberation—all our virtues. The myths contain the generous gifts that the gods offer us. All we have to do is learn to find them, recognize them and use them in our lives.

Introduction

Dionysus is perhaps one of the most mysterious gods of the ancient world. One of his key characteristics is movement: he penetrates everywhere — in all countries, to all peoples, in all religions. He has an incredible number of names, epithets and attributes, he can take a lot of different guises, he amazes with his numerous epiphanies and metamorphoses. The deeper we go into the study of Dionysus and try to get to his origins, the more clearly we feel a great delight and awe, because we find ourselves as if involved in the mystery of life itself, inevitably transforming ourselves.

Dionysus is the “archetypal image of indestructible life,” the prototype of inexhaustible life, he symbolizes the creative and fruitful power of nature in all its diversity. Dionysus is associated with winemaking and fertility, abundance and pleasure. He produces intoxication by the beauty of Nature, by bringing inner states beyond time and space that allow us to touch the mystery of life.

Dionysus is the gift of enthusiasm[1], the joy of true existence, the joy of prosperity and growth. And at the same time, he is a dark spirit of the underworld, who knows the mysteries of life and death.

Dionysus is a suffering god, sometimes reaching the point of complete madness. At the same time, he is a jubilant god in a state of ecstasy[2].

Dionysus possesses an infinitely powerful ability to penetrate into the depths of matter, and at the same time remain in the solar heights of Zeus’s throne.

Dionysus is the one who spiritualizes matter, the Demiurge of the human soul.

Origins

More than three millennia separate us from the first historical references to Dionysus (approximately 14th-13th centuries BC) which have come down to us and which were deciphered in the middle of the 20th century. Despite all the research, especially plentiful in the last century, we still do not reliably know what was the history of the appearance and penetration of the cult of Dionysus into Greece, which, according to the generally accepted version, took place around the 8th-7th centuries BC.

But one thing is certain. The name of Dionysus is associated with the greatest phenomena in the spiritual life of Greece, either directly – within the teaching of the Orphic and Pythagorean doctrines and their corresponding sacraments – or indirectly, through the presence of the image of Dionysus, his spirit, in the cults of other gods.

In Crete, we find one of the most ancient symbols, which was one of the attributes of Dionysus-Zagreus as the hypostasis of the Zeus of Crete. This is the Labrys—an axe that carves the way to the light, both inwards and outwards[3]. With it, the god whom the Greeks called Ares-Dionysus created the world and carved out the First Labyrinth.

“This is the story: it is told that this Ares-Dionysus, a very ancient god of the earliest times, descended to earth. There was nothing created, nothing embodied; there was only darkness, only gloom. But, from on high, this Ares-Dionysos was given a weapon, the Labrys, and was told that with it he is to forge the world.

“Ares-Dionysos, in the midst of this darkness, begins to walk in a circular way…

“Behold, Ares-Dionysus begins to walk in circles and, with his axe, he carves out the darkness and opens a furrow. The path which he opens and which gradually becomes illuminated is called the labyrinth, that is to say, the path carved with the Labrys.

“When Ares-Dionysus, after carving and carving, reaches the very centre of his path, he discovers that he no longer has the axe with which he entered the labyrinth. Now his axe has become pure light; what he holds in his hands is a fire, a flame, a torch that illuminates perfectly, because he has performed a double miracle: he has carved the outer darkness with one edge of the axe and he has carved his own inner darkness with the other edge of the axe. To the extent that he has made light without, he has made light within; to the extent that he has broken through without, he has broken through within. Thus, when he reaches the centre of the labyrinth, he finds the centre of the path: he has gained the light and he has gained himself.”

(Delia Steinberg Guzmãn , article on “The Labyrinth”)

In the Histories of Herodotus we read that the cult of Dionysus was brought to Greece from Egypt. Plutarch[4] writes about the identification of Dionysus with Osiris, telling the Egyptian legend about the war of Apophis[5] against Zeus, during which Osiris, who sided with Zeus and won the victory with him, was adopted by him and given the name Dionysus.

According to Greek historians, the inhabitants of the city of Nisa in India, located at the foot of Mount Meros (the only place in the country where ivy grows), said that they descended from Dionysus, who came from the West with his army. They said that Dionysus founded cities, established laws, taught Indians how to make wine and keep fruits, taught them how to worship the gods (by playing cymbals and drums) and how to dance circular dances.

H.P. Blavatsky, in “Isis Unveiled,” writes that “Bacchus, as Dionysus, is of Indian origin. Cicero mentions him as a son of Thyone and Nisus. Diovnusofi means the god Dis from Mount Nys in India. Bacchus, crowned with ivy, or kissos, is Christna, one of whose names was Kissen. Dionysus is preeminently the deity on whom were centred all the hopes for future life; in short, he was the god who was expected to liberate the souls of men from their prisons of flesh.” (H.P. Blavatsky, Isis Unveiled, vol.II, ch. XI)

Among the ancient Thracians, we find the myth of hierogamy between the God of Thunder and Mother Earth. “Dionysus” was presumed to have been born from their union. We also know the Thracian names of Dionysus — Sabos and Sabazios, as well as Baseareus, which means “dressed in a long fox’s skin.” The Thracians associated the practice of divination with the cult of Dionysus.

In Middle Eastern mythology, myths were widespread about the disappearance of a God, his descent into the underworld, accompanied by the fading of life on earth. These ideas were based on the ancient Sumerian myth of Dumuzid (Tammuz) and Inanna (Ishtar). A number of researchers compare Dionysian rituals with those of the Middle East in honour of the Babylonian Dumuzid.

According to Apollodorus, Cybele, the Mother of the Gods, cured Dionysus of the madness with which Hera had afflicted him, and initiated Dionysus into her mysteries, and he begins his triumphal march across the earth from Phrygia, accompanied everywhere by frantic dancing and music from the aulos and drums.

According to H.P. Blavatsky, mystics and initiates of all time clothed their knowledge in symbols and gave them the form of myth. The garments of the truths conveyed were different, but the essence remained unchanged. In all cultures of the ancient world there were myths about dying and resurrecting deities. They tell not only of the rhythms and cycles of the plant world. Their main purpose is to show the inner path on which the human soul travels from the moment of its descent into matter, and how it can return to its origins. Philosophically, the events recounted in these myths are not fundamentally different. Dionysus, Osiris and Jesus all represent the immortal principle of the human soul, and their life-stories not only describe the stages of the descent-ascension, but also allow us to recognise all that needs to be done to awaken “eternal life” within us.

Names

“Ogugia calls me Bacchus; Egypt thinks me Osiris;

The Musians name me Ph’anax; the Indi consider

me Dionysus;

The Roman Mysteries call me Liber;

the Arabs, Adonis!”

Ausonius[6] (Isis Unveiled, Vol. II)

From the point of view of the Neo-Platonists, a name is a “powerful symbol,” which always coincides with the named entity. In fact, it is the being itself. “…he who knows the names knows also the things named.” (Plato, Cratylus, 435 d)

The name “Dionysus” is translated as “God (from) Nisa,” “Child (son) of Zeus,” “God of light on Mount Nisa.” Zeus is “Life,” “Light”; “God”; “he who shines”; in his name he carries the meanings of “luminosity” and “day” (On one of the black-figure vases next to the infant Dionysus, who has just emerged from Zeus’s thigh, there is an inscription: “The Light of Zeus”).

The most ancient hypostasis of Dionysus was Zagreus —the son of the Cretan Zeus (who took the form of a winged serpent or dragon) and Persephone. He was torn apart by the Titans and saved by Athena, put together again by Apollo and reborn from Rhea (or Demeter). Zagreus (Ζαγρευς) was “the Great Catcher”, a chthonic demon, “catcher of souls”. In different sources he was the son of Zeus (god of life), or the son of Hades (god of the souls of the dead).

From the ancient myth of the dismemberment of Zagreus stretches a definite thread to Iacchus, the son-husband of Demeter, or the son of Zeus and Kora-Persephone, who was celebrated in Eleusis.

Dionysus-Iacchus was worshipped as the final liberator (Leii, Lieber) of Kora- Persephone from the kingdom of Hades, bringing resurrection to new life. According to other myths he also brings his mother Semele out of Hades and raises her to Mount Olympus. He is the one who grants every soul the right to a brighter heaven.

According to the Olympian Theogony, Dionysus is the god of fertility, patron of vine-growing and winemaking, “twice-born.”

In the classical Greek myth of Dionysus we sense a noticeable shift toward the heroic. Dionysus is no longer just a god, but a god-man, in whom the divine and human natures meet and are joined together.

The Myth of Zagreus

From the union of Zeus and Kora-Persephone, whom Zeus marries in the form of a winged serpent (dragon), Dionysus Zagreus, a horned baby (or a bull-headed child) is born. Zeus, seeing his son, immediately fell deeply in love with him, gave him his scepter and placed him on his right on the throne: “Zeus reigns over everyone, and Bacchus reigns over Zeus.”[7] The baby, in imitation of the great god, began to shake lightning and hurl thunderbolts with his tiny hand.

Zeus’s wife, the jealous Hera, decided to kill the baby, and when Zeus once left Olympus, she persuaded the Titans to attack Zagreus and tear the baby to pieces. Hera distract ed the Curetes[8] who were guarding the cradle with the baby, while the Titans prepared to attack.

In order not to frighten the divine infant with their black chthonic faces, the Titans rubbed them with chalk. They entice him with various toys: a mirror, knuckle-bones (astragalos), a sphere, a spinning-top (romvos), an apple, a cone (kohnos), a pokos (a tuft of wool or donkey hair). Zagreus, playing carelessly, picks up a mirror. Charmed by the reflection, he drops his guard, and the Titans grab him.

Zagreus frightens the Titans by turning into a young Zeus, then into old Cronus, who creates rain, into a lion, a horse, a horned dragon or a snake, a tiger, and finally a bull. The Titans retreat, but Hera, with her ferocious roar, spurs them into action. The Titans and Zagreus begin a battle, as a result of which Zagreus is torn apart into 7 (or 14) parts. Athena manages to save the heart of Dionysus-Zagreus, puts it in a casket and gives it to Zeus. Zeus incinerates the Titans with lightning, and from their ashes humans appeared, combining two principles—the good one being Dionysian (since the Titans ate the flesh of the God) and the bad being the dark and titanic. Rhea (or Demeter) collected parts of the body torn apart by the Titans and brought Zagreus back to life.

There is another version of the myth, according to which the Titans themselves handed over the torn heart of Zagreus to Apollo for resurrection, and he put it in the coffin-ark by the Delphic tripod.

According to a third version, Zeus swallowed the heart of Zagreus or crushed it and, mixing it with ambrosia, gave this drink to Semele, the “earthly Demeter,” who gave birth to Dionysus the God-man (Herodotus even gives the exact date of birth — 1544 BC).

Philosophical content of the Myth

The myth of Dionysus-Zagreus formed the basis of the Orphic doctrine. The philosophical understanding of the mythology of “dismemberment” was continued and completed by the Neoplatonists.

According to Orphic texts, Dionysus is the god of the last cosmic era; he is preceded by Phanes, Night, Uranus, Kronos and Zeus as rulers over the world, as reported by Sirion and Proclus.

The arrival of Dionysus-Zagreus, the ruler of the sixth era, symbolizes the descent of the divine into the world of soul-body divisibility, into the world of plurality. Dionysus embodies the World Mind, the World Soul, capable of divisibility and the birth of individual souls. That is how he differs from Zeus, who is the World Soul and World Mind in their absolute indivisibility, or singularity. It is this division (dismemberment) of Dionysus and his penetration into the depths of matter (the devouring of the body of Dionysus by the Titans[9]) that becomes the central event in the fulfillment of the world mystery. As a result of this universal tragedy — the murder of God — Dionysus won a victory over this world of matter, spiritualizing and reviving it. The result of the fulfillment of the mystery is the cleansing of the world from evil, the introduction of divine fire and good into it through the sacrifice of himself by God in the person of Dionysus.

The heart of Dionysus is the only part of the body that the goddess Athena could save. In other words, the divine is in the heart of man. Losing one’s heart means losing one’s human form. The key to the salvation of the heart is wisdom personified by Athena, and thoughts of the divine, according to Plato.

The Titans lured the baby with toys by deceit, “when he looked at a false image in the mirror.” According to Olympiodorus and Proclus, Dionysus’ looking in the mirror had a complex mystical meaning. Proclus wrote: “…they say that Hephaestus made a mirror for Dionysus. When he looked into it and saw his own image, he proceeded to the universal divisible creation.” (Proclus, Commentary on Plato’s Timaeus).

According to Olympiodorus, “When Dionysus had projected his reflection into the mirror, he followed it and was thus scattered throughout the universe. Apollo gathers him and brings him back to heaven, for he is the purifying God and truly the savior of Dionysus.”[10]

From the writings of Proclus it is known that Dionysus was dismembered by the Titans into seven parts. This division of Dionysus helped him penetrate into all spheres of the universe, which also consisted of seven parts.[11]

Dionysus-Zagreus undergoes an endless series of transformations, because matter itself is infinite, and in order to penetrate into its ultimate depths it is necessary to go through all its endless images and forms, to embrace the whole infinity of material becoming in general. Apollo finds and reunites the members of Dionysus, so that the reunited many now become order and harmony.

The Dionysian principle within us calls out to the divine, prompts us to ask questions about death and immortality, allows us to purify ourselves and be reborn, awakens higher intuition and mystical insight. The titanic principle of the soul is embodied by the elemental forces that cause man’s “dissipation”, departure from the center and oblivion of his true nature. Only heroic enthusiasm, striving toward the divine, helps us to gather the soul into a whole.

The Dionysian mysteries were not revealed to everyone; their initiatory mystery was kept carefully hidden. They were ancient forms of initiation and ascent to the divine, powerful instruments of healing and transmutation. But, as has happened many times in history, when sacred rituals lose their true purpose and a deep understanding of their essence is betrayed, they are immediately distorted. Moreover, without prior purification, preparation and training, they can become the cause of true madness, of losing one’s humanity. Thus, in time, the word “orgy” (ὄργια), which originally meant “ritual,” “sacrifice,” “sacrament,” the sacred acts in the mysteries of Demeter and Dionysus, gradually turned into a mad frenzy.

As H.P. Blavatsky writes, Orpheus becomes the one who purifies the Dionysian mysteries from their gross and earthly anthropomorphism and establishes a mystical theology based on pure spirituality. Orpheus revived the Mysteries of Dionysus with new force and depth, combining “divine frenzy” with catharsis. Through purification and initiation, by leading the “Orphic” way of life, it was possible to free oneself from the titanic element and become a bakhos (someone who has awakened Dionysus within themselves); in other words, to liberate the divine—the Dionysian—from the titanic and to become united with it.

“To look at oneself is philosophical,

the ability to rise above oneself is heroic,

And to touch eternity is mystical.”

(Antun Musulin)

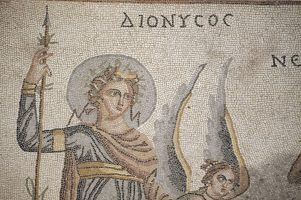

Image Credits: By Dosseman | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 4.0

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By Dosseman | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 4.0

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

Article References

The word “enthusiasm” comes from the ancient Greek ἐνθουσιασμός “(divine) inspiration, delight”. In European languages, the word came from the Latin enthusiasmus. It is a special “state of grace,” the absolute “fullness of being,” in which there is neither time nor space, but only abiding in eternity, in God. The ancients interpreted ecstasy as the departure of the soul from the body. It is a state of going beyond one's own limitations, an experience of the highest degree of wonder, inspiration and exultation. On the island of Tenedos, archaic coins have been found depicting a double-edged axe combined with ivy. The national emblem of Tenedos was an axe - the labrys. Plutarch, Isis and Osiris. Apophis in Egyptian mythology is a huge serpent, personifying darkness and evil, the primordial force personifying Chaos, the eternal enemy of the sun god Ra. Apophis wanted to swallow the sun and plunge the Earth into eternal darkness. It often acts as a collective image of all the enemies of the sun. Decimus Magnus Ausonius was a fourth-century Roman poet and rhetorician. Orphic verse as reported by the Neoplatonist Proclus. Curetes are demonic creatures from the retinue of the Great Mother of the gods, Rhea-Cybele The word “titan” (ancient Greek Τιτᾶνες, singular Τιτάν) comes from a verb that means “to spread in different directions”. According to Hesiod, this word comes from the Old Greek verb. τιταίνω — “stretch, spread”. There is also another epithet of Apollo — Dionysodot. Macrobius. Commentary on The Dream of Scipio, 1, 12, 11.

What do you think?