Living in a One-Dimensional World

Article By Istvan Orban

Ken Loach’s latest film – I, Daniel Blake – has received mixed reviews and has given rise to a lot of debate. One of the key elements of the film is how the benefits system in the UK places people in a humiliating and depressing situation, where they are no longer individuals but just claimants, faceless numbers, a problem that has to be solved.

Ken Loach’s latest film – I, Daniel Blake – has received mixed reviews and has given rise to a lot of debate. One of the key elements of the film is how the benefits system in the UK places people in a humiliating and depressing situation, where they are no longer individuals but just claimants, faceless numbers, a problem that has to be solved.

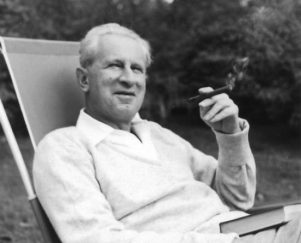

The all-pervading bureaucracy of industrial and post-industrial societies is not a new phenomenon and has been a focus of contemporary philosophy since the end of World War II, especially by the so-called Frankfurt School, which was very critical of this issue. One of the thinkers associated with that school was the sociologist and philosopher Herbert Marcuse, who wrote his eye-opening book about the ills of advanced industrial societies. One-Dimensional Man (1964) inspired many subsequent social movements, including the French strikes in 1968 and the New Left. Many of the statements in his book are still relevant today, when mass production oppresses most values and makes everything conform to an established, but degenerate system.

Marcuse claims that this system, based upon positivism and technology, provides people with a convenient life, but takes a lot from them in return, especially their time. Consumerism extinguishes the value of the unique and creates false needs. For example, we buy new gadgets all the time, because the ads tell us they are bigger (or smaller), faster, nicer and make us happier; however, we rarely stop to ask the question: do we really need this? One of the features of today’s societies is growing demand and constant change: new trends, new vibes, new designs. But if we look closer, we can see a pattern, the repetition of themes that helps the masters of the system to maintain the status quo and keep people engaged. In music, for example, people have danced to the same chords for the last few decades and only the rhythm and singers are different. The “new” hit songs are old and their lyrics are based upon the needs of the mass. Consumerism focuses on the instincts and supports self-satisfaction and selfishness. Meanwhile, we can see the devaluation of ethics and core human values, such as politeness, comradeship or trustworthiness.

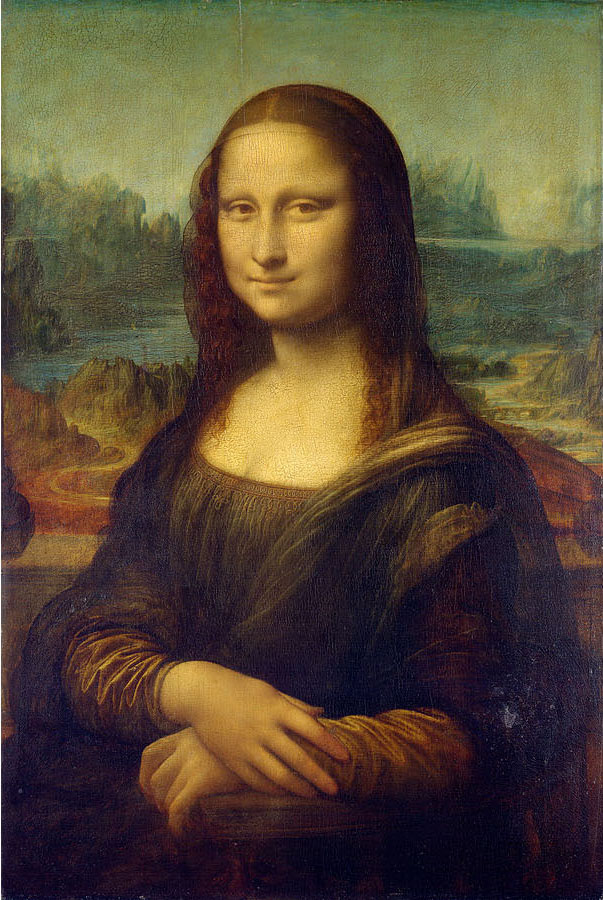

Marcuse introduces the concept of “repressive desublimation”, the process of flattening out higher culture. In his interpretation, reality has surpassed culture, with the result that the hopes and truths expressed in higher culture seem not to be relevant any more. Culture had always been a kind of sublimation and kept at some distance from reality. In this sense, it could express higher ideas and subtle emotions that could negate the current, lower values of the societies. But as consumer society absorbs the culture, putting an end to its two-dimensional character, there is no sense in keeping the distance any more, and the problems of the old-fashioned heroes and heroines are seen as mere romanticism. The masterpieces that were once presented to the world, provoking and awakening the small group of people who read them, are now available to all. In this world, Bach is only background music in shops, Shakespeare is a good script for best-selling movies, and the poems of Baudelaire or Shelley are just good gifts for Christmas alongside other products in a store.

Of course, in the one-dimensional world it is not obligatory to live a one-dimensional life, because it is our choice how we live. As Epictetus, the great Roman philosopher, said, many of the things that we think belong to us are in fact not ours, like possessions or fame; but how we think, feel or act does depend on us. Marcuse says that “the great refusal” can be a good alternative for the suffocating milieu. We can live our life in an anti-consumerist way, which means we may buy what we really need, thus avoiding unnecessary consumption and work. In this way, we will have more time for ourselves, our friends and family or a chosen community, and we can explore the miracle of the multi-dimensional life. As in Ken Loach’s film, the hero represents the disappearing human values that bring together people from different backgrounds.

Image Credits: By Harold Marcuse | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 3.0

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By Harold Marcuse | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 3.0

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

What do you think?