Spiritual Exercises in the Western Philosophical Tradition

Article By Julian Scott

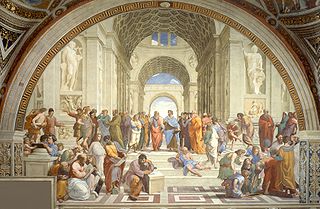

Although modern philosophy is mainly an intellectual pursuit, it has had immense impact on the shaping of our world. The philosophy of Francis Bacon (1561 – 1626) was largely responsible for the current scientific worldview and the explosion of technology; Auguste Comte (1798 – 1857) schematized the foundations of a theory of linear progress in history that has dominated the Western worldview since the 19th century to this day; and the philosophies of Hobbes (1588 – 1679) and Hume (1711 – 1776) promoted the idea of a lack of free will in human beings, whom they saw as being at the mercy of their passions, an idea which also continues to be prevalent nowadays. But modern philosophy has not been seen as a method for the transformation of the human being; in other words, it cannot save us from our unruly passions and convert us into serene sages at one with ourselves and the universe. In the world of ancient Greece and Rome, however, this was precisely the goal of philosophy: not only the transformation of our vision of the world, but also the metamorphosis of our personality, as Pierre Hadot[1] expressed it. As such a transformation is no easy matter, all the Greco-Roman philosophical schools had a series of what Hadot calls “spiritual exercises” to achieve this aim.

Although modern philosophy is mainly an intellectual pursuit, it has had immense impact on the shaping of our world. The philosophy of Francis Bacon (1561 – 1626) was largely responsible for the current scientific worldview and the explosion of technology; Auguste Comte (1798 – 1857) schematized the foundations of a theory of linear progress in history that has dominated the Western worldview since the 19th century to this day; and the philosophies of Hobbes (1588 – 1679) and Hume (1711 – 1776) promoted the idea of a lack of free will in human beings, whom they saw as being at the mercy of their passions, an idea which also continues to be prevalent nowadays. But modern philosophy has not been seen as a method for the transformation of the human being; in other words, it cannot save us from our unruly passions and convert us into serene sages at one with ourselves and the universe. In the world of ancient Greece and Rome, however, this was precisely the goal of philosophy: not only the transformation of our vision of the world, but also the metamorphosis of our personality, as Pierre Hadot[1] expressed it. As such a transformation is no easy matter, all the Greco-Roman philosophical schools had a series of what Hadot calls “spiritual exercises” to achieve this aim.

What is the meaning of spiritual exercises? The term probably originates in the exercitia spiritualia of St Ignatius of Loyola, founder of the Jesuit religious order in the 16th Century. But Ignatius himself developed these exercises on the basis of early Christian philosophy, which in turn derived from the exercises already existing in the philosophical schools of antiquity, where they were referred to under the general term askesis, from which we have the word “asceticism”. The Greek and Roman spiritual exercises were not exclusively “ascetic” in the modern sense, however, as we shall see. This modern meaning of the word ‘asceticism’ arose from a Christian, mainly monastic application of the concept.

So what were the spiritual exercises of the ancient philosophical schools, and would they still be useful for a spiritual seeker of today?

For the ancients, the chief cause of suffering and disorder in man and the world were the passions (anger, greed, lust, etc.). Consequently, philosophy was seen as a therapy for the passions and its aim was to bring about a state of calm in the human soul. Consequently, one of the main spiritual exercises was to cultivate this inner calm. How did they propose to achieve it? First of all, by transforming the way we see the world. Ordinarily, we give great importance to the acquisition of wealth and fame. Our society today is still based on such criteria. But as Socrates says in The Apology (Plato’s account of the trial and death of Socrates): “Are you not ashamed that you give your attention to acquiring as much money as possible, and similarly with reputation and honour, and give no attention or thought to truth or thought, or the perfection of your soul?”

To counteract this tendency in the human being, Plato proposed philosophy as a “training for death”. In other words, in the knowledge that we will all die some day, we should prepare ourselves to live without a body, and this would mean dedicating ourselves to the intangible things of the soul.

One of the main exercises in all philosophical schools was therefore to practise “disidentifying” (to use a modern term) from our senses and freeing ourselves from what they called the “slavery of the desires”, which force us to act in ways we don’t actually want to. The Platonic exercise par excellence consisted in “separating the soul as much as possible from the body and accustoming itself to… concentrate itself until it is completely independent.”[2] (Socrates himself was an excellent example of such detachment, showing an ability to withstand heat and cold, pleasure and pain, while he pursued his philosophical investigations within himself, as we find described in Plato’s Symposium).

A further fruit of this training is that it enables the philosopher to free himself from his subjective points of view (which result from his subjection to his personal likes and dislikes, fears and desires) and rise to a more objective and universal perspective. This also helps us to see things in proportion: if you realise that as individuals and even as humanity, we are only a tiny and fairly insignificant part of reality, then we will not be so fazed by all the joys, sorrows and vicissitudes of human existence.

This attitude results from another type of spiritual exercise, which is the meditation on the nature of reality and one’s own place in it. Unlike many of the modern philosophers, the ancients did not think of such meditation as a purely intellectual exercise, since it must also be practised in everyday situations in order to be validated. These philosophers were not “armchair thinkers”: Socrates, for example, was tried in court and sentenced to death. He remained calm, cheerful and even humorous, both in court and as he awaited death in his prison cell. And Plato was once sold into slavery (but subsequently ransomed by a friend). None of them had an easy life, and philosophy was often compared to the training that athletes had to undergo in order to compete in the Olympic games. Indeed, in ancient Greece, philosophy was actually taught in the gymnasium.

Philo of Alexandria, a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher of the 1st century BC, made a list of different spiritual exercises used in the philosophical schools of his time. These included: thorough investigation, reading, meditations, listening, attention, self-mastery, indifference to indifferent things, therapies of the passions, remembrance of good things and accomplishment of duties.

The Stoic philosophers particularly recommended continuous vigilance and presence of mind, a self-awareness that never sleeps, and concentration on the present moment. They, and other schools before and after them, recommended reflecting at the beginning of the day on what awaited them and how they would respond to it; followed by an examination of conscience at the end of the day in order to pursue a path of continual self-improvement. Some schools also recommended examining one’s dreams, and even controlling them, as well as preparing oneself for sleep by calming the passions and awakening the rational faculty with “excellent discourses”.

In short, we can see that all these exercises were a natural part of “philosophy as a way of life”. They recognize the mind of man and its importance – the need to think things through for ourselves – as well as the need for regular practice and implementation of our moral values and principles, and the need to see ourselves as part of a greater whole which is governed by a “universal reason” or intelligence.

The Neoplatonist philosopher Plotinus (204/5 – 270 A.D.) described three stages of the philosophical path towards what he called The Good (the highest good that man can conceive): “We are instructed about it by analogies, negations… (the thinking-understanding process). We are led towards it by purifications, virtues… (virtue seen as a means of detaching ourselves from the senses) and ascents into the intelligible world” (the mystical states of ecstasy experienced by Plotinus himself).

These spiritual exercises are truly timeless and can definitely be practised with beneficial results today. They allow us to rise up to the “life of the objective spirit”, as Pierre Hadot puts it, while keeping our feet on the ground, improving ourselves day by day and maintaining an increasingly strong sense of connection with the rest of nature and the universe, of which we are a part.

Image Credits: By http://www.cambiaste.com/it/asta-0175-2/pietro-della-vecchia-venezia-1603-vicenza-1.asp | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By www.cambiaste.com/it/asta-0175-2/pietro-della-vecchia-venezia-1603-vicenza-1.asp | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

Article References

[1] French historian of ancient philosophy, author of Philosophy as a Way of Life, Blackwell 1995. [2] Plato’s Phaedo 67c

What do you think?