The Art of Devotion

Article By Kanika Mehra

In the wee hours of the morning, Emperor Akbar awoke to the sweet melodious singing of Haridas, guru of the celebrated singer of his court, Tansen. Haridas had been singing a dawn raga. Overwhelmed, Akbar inquired why Tansen was not able to sing like his guru Haridas. Tansen replied that there was one big difference between him and his teacher; while he sang for his lord Akbar, The Great, Haridas sang for the Lord of the universe – God.

In the wee hours of the morning, Emperor Akbar awoke to the sweet melodious singing of Haridas, guru of the celebrated singer of his court, Tansen. Haridas had been singing a dawn raga. Overwhelmed, Akbar inquired why Tansen was not able to sing like his guru Haridas. Tansen replied that there was one big difference between him and his teacher; while he sang for his lord Akbar, The Great, Haridas sang for the Lord of the universe – God.

Tansen refers to the devotional element that elevates Haridas’s art to a higher experience, the realm of the divine, the soul-stirring eternal and infinite. This aspect of devotion has inspired ancient Indian artists across all genres and can be seen in various expressions of dance, poetry, music, architecture and painting. In doing so, it is evident that ancient Indian artists deliberately aspired to capture the invisible and unlimited through visible and limited means, thus creating a bridge between the formless and the form. The devotion we are talking about here is not towards a personal god or a religious entity, but the divine that represents the Ideal, the Absolute.

Devotion is a form of love, a powerful force of attraction that propels one forward, not with blind belief, but with a conviction that comes from firsthand experience, from knowing. It is noteworthy to mention that the object of this unique form of love need not be tangible or quantifiable. It fuels the artist who is on an endless path leading to the Mystery in order to capture a deeper and ever more accurate grasp of the archetype of Beauty. Therefore, devotion is a key that enables the aspirant to move from what is known and familiar, to the realm of the unknown, the unlimited and eternal.

Dr. Anand Kentish Coomaraswamy said that Indian art is essentially religious, adding that the conscious aim of Indian art was the imitation of Divinity. The great challenge, therefore, was to express in finite terms the Infinite and Unconditioned nature of the Divine. Sankaracarya prayed: “O Lord, pardon my three sins: I have in contemplation clothed in form Thyself that has no form; I have in praise described Thee who dost transcend all qualities; and in visiting shrines I have ignored Thine omnipresence.” (1) The aspiration is to touch the arupa, the intangible, using tangible means. Hence, art for art’s sake was unknown in India.

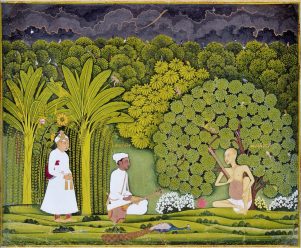

One must observe the holistic quality about Indian art; a unity of many forms and artistic experiences. Whether it is miniature painting, music, or rock cut temples, each is a testament to the strength of devotion and the persistence of the artist. Annie Besant beautifully states, “Indian Art is a blossom of a tree of Divine Wisdom, full of suggestions from worlds invisible, striving to express the ineffable, and it can never be understood merely by the emotional and the intellectual; only in the light of the spirit can its inner significance be glimpsed.” (2) It follows that a true artist must deliberately try to ensure that his art not become an expression of his opinions, thoughts and feelings, since these would only adulterate and limit the infinite principle of Beauty, making it subjective and partial. Instead, his art must act as a channel through which to objectively capture and transmit the principle of Beauty.

It is said therefore, that many ancient Indian artists never saw themselves as the creators of their art. Countless anonymous artists often worked together on a single artwork. They did not assume ownership of their creations which were intended as offerings. Instead, the artist himself was unimportant; a humble channel of transmission, whereas the Divine is the only true creator.

So influential was this devotional aspect, also in the realm of poetry and literature that an entire genre known as the bhakti movement developed to celebrate this devotion, in an almost trance-like surrender to the divine, which was sometimes related to as a teacher, sometimes a parent, or at times even as a lover. Through the bhakti movement we see poets reaching out to the mysterious, the beauteous and the sacred. Perhaps one of the most prominent examples of this is the 15th century poet Kabir who wrote beautiful dohas, verses, to exemplify his devotion.

What is seen is not the truth.

What is, cannot be said.

Trust comes not without the seeing,

Nor understanding without words.

The wise comprehends with knowledge.

To the ignorant it is but a wonder.

Some worship the formless God,

Some worship his various forms.

In what way he is beyond these attributes

Only the knower knows.

That music cannot be written,

How can then be the notes?

Says Kabir, Awareness alone will overcome illusion.

In the genre of dance too, we see that all of the classical systems were intended as offerings to be performed exclusively in temples, as a way of emulating the presiding deity and channelizing its associated archetypes through movement and sentiments. The 12th century Thillai Nataraja Temple in Chidambaram (Tamil Nadu) depicts sculptures in 108 Bharatnatyam poses, intricately carved in rectangular panels. Furthermore, the 18 arms of the central Nataraja sculpture express Bharatnatyam mudras, as if the language of dance is employed to reach out to what the deity represents.

On the occasion of World Philosophy Day, Mohini Attam dance exponent Miti Desai quotes scripture to describe her own understanding of the role of dance: “From the formless comes the form, and the form takes you back to the formless.” She explains that classical Indian dance is a ladder that might give you a glimpse of the formless, if one might dare to climb its rungs. Traditionally, dance is known as Brahmananda-sahodara, the twin brother of Brahma the Creator himself.

Ancient cultures proposed a variety of techniques to channelize divinity in our lives.. Ancient Egypt speaks of the concept of Ma’at – to do justice in life, by daring to fulfill one’s potential; or one might say in the Indian tradition to actualize one’s Svadharma. Similarly, the Buddha prescribed the 8-fold path.

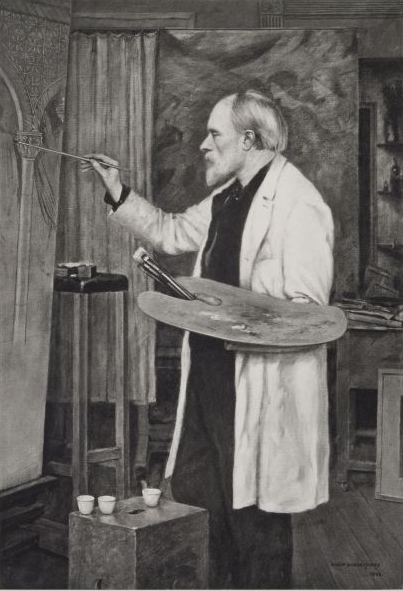

Essentially these are different ways to speak of living life as a philosopher, which classical traditions universally seem to offer. I sometimes wonder: what if we too might yearn for beauty in our own lives as the ancient artists did? Could there possibly be a way to make our own lives works of art? By using our lives as a canvas, and virtues as our palette of paints, each person has the potential to become the artist of his own life. Instead of exercising our vocal chords and practicing the musical notes, we can do our riyaaz, our daily practice, by practicing virtues to reveal the beauty and ethics that lay in our hearts. Perhaps we could use the inspiration from the ancient artists to live life with a devotion to Truth and objectivity, beyond the ego and subjective opinions or beliefs that cause separation. Perhaps we can be driven by a devotion to Truth, and fulfill a purpose, to become a channel of beauty and goodness.

Image Credits: By Eugene a | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By Eugene a | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

Article References

Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. Essays on National Idealism. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. 1981.

What do you think?