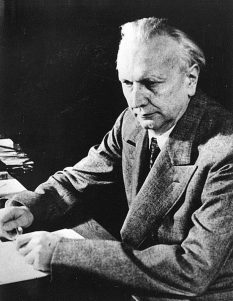

Karl Jaspers: Philosopher of Otherness

The biography of Karl Jaspers gives an indication of the immense scope of his work. He began by studying law, then moved on to medicine, becoming a doctor specialising in psychiatry, and finally ended up as a professor of philosophy at the University of Heidelberg.

The biography of Karl Jaspers gives an indication of the immense scope of his work. He began by studying law, then moved on to medicine, becoming a doctor specialising in psychiatry, and finally ended up as a professor of philosophy at the University of Heidelberg.

One of his first works was entitled Psychology of World Views (1919). In it he put forward the theory that all world views contain an element of pathology and that, in order to come closer to truth, the human mind must free itself from the ‘objectivized cages’ which seek to contain thought within certain safe limits. The mind must therefore go beyond its world view in order to discover truth for itself. This theory developed into his concept of ‘limit situations’ in which the human reason is confronted with its own inadequacy, leading it to ‘transcend its own contents’ and make contact with something other than itself, which in philosophy is known as the concept of ‘alterity’ or ‘otherness’. If there is truthful knowledge, he claimed, ‘it would be a cognitive experience in which reason is transfigured by its encounter with contents other than its own form’ [Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – all further quotes in this article are from this source unless otherwise stated].

One of the ways of attaining this consciousness of otherness is through ‘intensely engaged communication with other persons, in which committed communication helps to suspend the prejudices and fixed attitudes of consciousness’. Another means is through what he called ‘ciphers’. These are to be found, for example, in the contemplation of nature, art, religious symbolism or metaphysical philosophy. As a result, he criticized Rudolf Bultmann’s idea of ‘scriptural de-mythologization’, which proposed that religion should be stripped of all its mythological and even historical elements to concentrate purely on its ethical teachings. For Jaspers, however, such mythological elements are an important way of approaching transcendent knowledge, as well as a means of discovering similarities in different systems of thought, thereby giving rise to a culture of tolerance.

Although he was sympathetic to religious ideas per se, he argued that any claims to transcendent knowledge could not be absolute and that orthodox religions often defeat the very purpose of religion by interpreting such ‘ciphers’ as literal truth or by being absolutist and dogmatic. Reason therefore has an important role to play in his idea of ‘Philosophical Faith’ (1948), which would always maintain a communicativeness and openness to dialogue.

Jaspers is considered to be one of the most important figures of German Existentialism, one of the principles of which is to ‘focus on man’s existence as the centre of all reality’ [Encyclopedia Britannica]. Jaspers’ own form of existentialism held that ‘philosophy must be guided by a faith in the originary transcendence of human existence, and that philosophy which negatively excludes or ignores its transcendent origin falls short of the highest tasks of philosophy.’ Like Kant, he accepted the limits of human reason, but unlike Kant, he argued for the possibility of obtaining a glimpse of something beyond the reason.

During and after the Second World War, his thought turned increasingly to politics and culture. Jaspers was one of the few German intellectuals who was not tainted by association with Nazism and he played an important part in the reform of German universities after the war. He believed that acknowledgement of national guilt was a necessary condition for the moral and political rebirth of Germany.

His observations of both Nazism and Communism led him to attack all forms of totalitarianism. However, he also saw that totalitarian tendency in the Western technocracies which he saw as oppressive of freedom and individuality. Culture, on the other hand, is always an important antidote to totalitarianism. Like Hannah Arendt, his former pupil and later an important influence on his thought, he saw the destruction of culture and the atomisation of society as eroding the freedom of individuals, making them easy prey for technocratic oppression.

He called instead for a ‘World Philosophy’ and advocated an international federation of nation states sharing similar constitutions and values.

Image Credits: By Mondadori Publishers | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

If any images used in this article are in violation of a copyright, please get in touch with [email protected] as soon as possible. Appropriate action will be taken.

What do you think?