The Anxieties of Youth

Article By Delia Steinberg Guzmán

posted by Kurush Dordi, April 27, 2017

It is not easy to define youth. Even if we do a lot of research, we will find that different authors throughout time have not been able to agree on an exact definition. Moreover, the concept of youth is so rich and varied in its meanings, so flexible and extraordinary, that it is impossible to find an objective, concrete and synthetic way of defining it.

It is not easy to define youth. Even if we do a lot of research, we will find that different authors throughout time have not been able to agree on an exact definition. Moreover, the concept of youth is so rich and varied in its meanings, so flexible and extraordinary, that it is impossible to find an objective, concrete and synthetic way of defining it.

As philosophers, we have enormous faith in youth and great hope in that future world that we speak about so often and of which we say so many things. We think that, deep down, none of us have ever stopped being young and, for one reason or another, have never stopped having certain anxieties either and, even though those anxieties may be more or less youthful, their roots are to be found in the same problems and in similar circumstances.

In general terms, we can accept what some people say about youth: that it is an intermediate state between childhood and maturity.

It is indeed an intermediate state, but not a unique or definitive one. It is, however, a very special state, because it emerges from the so-called “sweet unconsciousness of childhood” to enter almost at once into a sudden and immediate awakening to the inner, emotional, intellectual, physical and psychological realities that occur at this stage, which, however natural they may be, still have a strong impact on the personality of the young person.

When we speak about youth, we cannot speak solely and exclusively about those physical changes that occur and that mark the transition from childhood to adolescence; we also have to speak about other, very deep, associated changes, both psychological and mental.

If we listen to what the ancient traditional doctrines have to say, we would also have to consider that the change that arises in youth not only relates to an awakening of the psyche and the mind, but also to a re-emergence of the Self, that sleeping Higher Self which comes from the depths of time and needs a special moment in life to awaken and manifest itself.

We do not agree with those who say that youth begins with puberty, with sexual maturity. Nor should we make youth end when maturity appears and the human being becomes an adult. If this were so, we should ask ourselves when that maturity begins. Or does youth actually continue for much longer, not in its positive aspects, but rather in the negative ones, such as a lack of maturity in knowing what one wants?

So we see that we can’t impose limits. As the richness of the human being is infinite and the multiple expressions of human evolution are infinite, it is impossible to limit ourselves to strict definitions.

There is something of a new birth about youth; it is like being born again, even if one is still in a physical body that is expressed in a material and concrete form.

There is something about youth which is like opening one’s eyes to a new way of life, and it brings with it all the anxiety that this implies: having to face a new way of life. It is as if we were being born, but this time we are doing it alone, absolutely alone, because we feel that we are going to have to deal with all the anxiety of that new birth on our own.

Like every new state, this new youth to which one has just been born appears to be unstable, insecure and restless. It needs to put its roots down and can’t find where to do it. And that is the reason behind the anxiety we are referring to.

We can approach this anxiety from two points of view: there is a normal and logical anxiety, the one that is proper of growth, of the development of this human being who is born again when he stops being a child; it includes all the processes that are dealt with by conventional psychology. Another aspect that we are enormously interested in is the “other” anxiety, the one that is not so natural and proper of youth; it is the one that is brought about by the world around us with all its problems, and that is less natural and more overwhelming for the personality of the young person. Let’s start with the first one.

The psychology of the last hundred and fifty years tells us that youth cannot only be understood in terms of certain physiological and hormonal changes, important as they may be; other elements have to be taken into account, which are very typical and characteristic of this age and are of a psychological, intellectual and moral nature. Strangely, this psychology always approaches all the changes of youth as if they were pathological and abnormal. These changes are so many, so great and so important, that the young person must feel as though he is ill, and that what is happening to him is terrible.

The first thing a young person experiences is the need to assert a new personality. Suddenly, new concepts have to be expressed and there are no means available to do so. As a result, he has to strengthen the parts of himself that, although they appear childish, are the first ones that will enable him to express his young personality. There is a rejection of everything that has made up his previous world, because it is identified with childhood, with being small, not thinking, not feeling; consequently, everything that went before is bad and has to be left aside, rejected.

Included within that general rejection is the destruction of the image that the young person had of his or her parents; they are no longer the mum and dad in whom the child can seek refuge, nor are they the support they had once been; and when this image has been destroyed, then the image of all adults, the immediate family and all those who used to be a support network also collapses; everything that had been loved until that moment is now hated.

In the young person there is no middle ground: all the love that was expressed towards the parents is now turned towards new leaders. There are new aspects that have to fill the vacuum that has just been created and this awakens an enormous anxiety in the young person.

The figures of the teacher, or the priest, or the slightly older friend, or some political leader, now become larger. Sometimes young people seek support in fictitious leaders of their own invention, who represent the ideal, the archetypal and the perfect. Sometimes they become attached to historical figures who represent all that the young person would like to be and all his love is given over to them. But deep down, it is all about filling a hole. At the same time, this produces an enormous melancholy and nostalgia for that childish world that has slipped out of his grasp and will never return.

In this first stage, the young person has a great propensity for inner sadness. He feels that he has lost a world, but no one can explain it to him. He feels that he has just been born into another world, but in that other world nobody understands him. That sadness which is so private, so deep, never manifests externally; at the most, there is just a hint of melancholy. On the outside he displays an exaggerated cheerfulness, which is completely fictitious, with strident laughter and out of place attitudes, or shows of aggression or an exaggerated vitality which forces aggression to appear.

The young person also attacks his parents because he blames them for the loss of that world, and with a little sense of guilt he expects the parents to attack him as well, which he feels happens immediately. And here begins a chain reaction with a long succession of anxieties, misunderstandings, with daily arguments, constant confrontations and the fact of not being able to live together in harmony with those who until recently formed a closed and wonderful nucleus.

Faced with this situation, the young person responds in many different ways. One of these is the awakening of metaphysical ideas, which is very characteristic of youth; not in the sense of a perfectly elaborated philosophical metaphysics, but something simpler. The young person begins to ask himself, for the first time, what life and death are about. And he realises that he is not eternal, that he is within time, that he has grown and changed, that he will continue to grow and change and that he will disappear. And then he asks himself about what there is beyond.

Together with these metaphysical ideas, other ideas of a moral order appear. The young person is usually very strict at first, and in a way and with a morality that is very much his own and very personal, very rigid, especially towards others, but to some extent, also towards himself. If this were well directed, we would have the beginnings of a process that could gradually unravel the anxieties of youth and make them disappear. Unfortunately, however, it doesn’t happen like this and these first metaphysical and moral impulses usually just provoke among close family and relatives a contemptuous smile or some rather cruel mockery, that will cause very deep wounds in the young person.

From the intellectual point of view, several very different things can occur. Either the young person lets himself go completely, and we find those young people who were brilliant before and all of a sudden they stagnate and begin to fail in their studies; or the opposite happens to them, and they discover an ideal form of escape in their studies and try to intellectualise the whole problem they are going through, finding a wonderful path in the world of ideas and being able to describe everything that is happening within them in great detail. In this second case, they develop a great fondness for dialectics, without caring whether the ideas they are defending are true or not. They want to argue, to assert themselves, to demonstrate strength and ability. This makes them really happy.

Another typical reaction in young people is a certain egotism that psychologists call narcissism. They want to focus on themselves, to find all the answers in themselves, wanting to be original at all costs because to be oneself requires to be different from others and even to be somewhat eccentric. There is a need to attract attention, which can often been seen in basic things, such as fashion. But it is a very special kind of eccentricity, as it is intended to irritate adults a little. Moreover, it requires the approval of other young people in a similar situation, resulting in the creation of tribe-like groups.

There is one positive element in this period of youth, which is the awakening of friendship, even if it is painful and not taken advantage of enough. Maybe this is the only period in one’s life when one really knows what true friendship is. The friendships of youth are glorious, they are the only ones where everything is wonderful, where there is an ideal and extraordinary trust, where the friend is everything: an escape, a relief from inner problems, and also – because this type of friendship develops in a field which does not express itself in negative or morbid ways – it is almost like a trial run for what will later on become love. The friend is the moral support. And beyond these individual experiences of friendship, young people sometimes find another escape, that of the group, which they become part of because they need to feel strong and because they need the approval of those around them, because it is very difficult to walk alone.

According to the findings of psychology, the interests of young people are many and very varied. They tend to be interested in everything, but not for any length of time: they start something today and by tomorrow it is left aside; many things get started and almost none of them get finished. What is important is to be in motion, but they are not really interested in anything; there is a total apathy, because young people have to respond to an excess of stimulus from the family or from those around them, who are constantly throwing advice and recommendations at them about what to do or what not to do; so their behaviour is a defence reaction.

Generally, the problem is that young people are simply young and anxious. It is difficult to understand, but it is a reality.

Now let us consider another aspect. Our world, our anxious world, makes a bad situation worse by adding its own anxieties to the anxieties of youth. We will now list some of the elements that enormously aggravate the situation of the young person.

As philosophers, we should perhaps begin with the problem that we consider to be the most detrimental, the worst of all, which is the wrong approach of the educational system, a system that does not take the nature of young people into account, but is completely stereotyped and only focuses on the studies themselves, but not on the human being who is going to receive them or implement them. The result is either that adults send young people out, without any preparation whatsoever, into a cruel and competitive world where they feel totally incapable of fending for themselves, or else they overprotect them and keep them constantly trapped, preventing them from testing their strength and going out into that world where, sooner or later, they will have to make their way. Either by excess or deficiency, the young person ends up with an inadequate education and is unable to express himself in the world.

Generally speaking, adults tend to make the typical mistake of reproaching young people by telling them that they are no longer children, but that they are not yet mature either, which is equivalent to telling them that they are nobody. Today there is a lot of talk of marginalisation, but it is we who unintentionally marginalise young people, because they no longer know what they are any more. And sometimes it is just one step from being psychologically marginalised to turning to crime. It is about stepping across a line which can sometimes be quite thin.

Initially it is only the moral authority of the parents that is questioned, but in the end, all forms of authority are thrown into doubt, with the result that social life becomes practically impossible and the young person no longer recognises or has any respect for anything at all. And as if this were not enough, this situation is cruelly exploited by advertisers, who take advantage of the natural enthusiasm of young people, who can so easily hate and love and embark on great adventures. All this is exploited by a shameless advertising industry, which promotes fads and fashions, ranging from clothes to anarchic lifestyles, from drugs to atheism, from the tactics of personal irresponsibility to the rejection of any established order.

Healthy young people cannot be exploited. So they have to be promised a thousand and one impossible paradises that will never be attained; and even if they are, the young will continue to feel anxiety and continue to be fertile soil for more of this anxiety-inducing advertising, creating more young people who don’t know what to do with their lives.

As if this were not enough, there are the natural responses of young people, which should not surprise us in the least. Nowadays, a couldn’t-care-less attitude is in vogue, and this is natural, because this apparent indifference is no more than a cry of desperation, a way of saying “what can I do?” When a young person looks for a job, he is asked for experience. The young person wants to be better, wants to be different, wants to achieve an ideal, wants to have a family, but he is only able to do this if his parents give him space. If not, he will have to wait a long time, not knowing what he will do or when. Even if he decides to study, in most cases he won’t have the opportunity of applying what he has learnt and later on he will have to take any job he can, just to earn a living and feed himself.

In addition to this anxiety, another one appears: youth begins to fade and the young person begins to realise that he has done absolutely nothing. In these circumstances, the couldn’t-care-less attitude becomes the logical response. It is also logical that these young people will turn to protesting, whether in a passive and sterile way or aggressively and violently. And there are also statistics that tell of the “solution” to this fruitless search, which is the deliberate ending of one’s own life.

Previously, when surveys were carried out on young people regarding what aspects of life they were most interested in, the most popular results were aesthetic values, moral values, metaphysical needs and religious concerns. Nowadays, polls show that in the first place come personal well-being, money, love, and only then some more abstract questions. But the main things that are highlighted are security, a quiet life and well-being.

Do they really feel that way, or have young people been pressurised into thinking and feeling like this?

It makes one wonder whether the great dreams of youth have died. We think not, but they are very difficult to find, and it is very difficult to get a young person to admit to what his great dreams are, as the poll experts claim that young people don’t usually tell the truth.

We are inclined to believe that these great dreams are there, but one has to know how to find them. These are the dreams that would eliminate anxiety little by little, but in order for that to happen they need to become reality. There is not one young person who, on the physical level, does not like beauty. There is not one young person who would reject harmony or good taste. So when they reject these things, it is as a protest, not because they have no love for the aesthetic, the beautiful and the pleasing. The other way in which this rejection is expressed is by “spitting in the face of what one can’t have”. All young people love health and like to feel strong, and yet they ruin their health and damage their own bodies. It is a form of rejection which is due to the belief that in the end there is nothing for them to do.

Young people can deny it on the outside, but deep down they all have pure and noble feelings. Nobody likes feelings that are constantly changing, that exist today, but will be gone tomorrow, that keep us in a permanent state of distress, anxiety and uneasiness. Every young person dreams of eternity. Every young person has a special place for the concept of love, even if they don’t want to admit it. Every young person dreams of things that are clean, pure, bright and wonderful, even if they refuse to recognise it.

Anarchy and disorder exist, but they are forms of anguish. There isn’t a young person who, intellectually, is not searching for wisdom. Curiosity, the desire to investigate, to know more and more things, is something typical of youth. It is like an unstoppable urge to penetrate all the secrets of the world.

Young people want to know, but this is difficult, because sometimes one has to start by removing veils, destroying ignorance and lighting torches in the midst of the darkness. Sometimes one has to discover that science not only destroys, but it also builds, that research brings us closer to the innermost laws of Nature, that science fiction is not enough to fill up all of our time, but that there are authentic laws that can be known without descending into fiction. Sometimes one has to destroy false concepts and discover all the beauty that there is in art, with authentic messages, and clear away those other parodies that one is supposed to accept, often because it is fashionable to do so. Sometimes it is necessary to show young people that it is not that they are atheists, but rather that they have nothing good or noble around them that they can believe in, and that even the image or idea of God has been bastardised and defiled. Sometimes one has to teach young people that they have to begin by recovering faith in themselves, so that then they can progressively climb step by step up the ladder of faith in all things until they reach God.

Who has not wanted or does not want to change the world? Who has not dreamt of that constant revolution that could allow us to sweep away everything bad and all injustices?

But it is good to realise that the revolution has to begin with oneself; by applying oneself to work, to one’s own responsibility and to a healthy ambition that will be a constant force propelling us forward. But this ambition should not be one of rejection, but one that is filled with an increasing respect for others.

There is not a single young person who does not dream of happiness. Happiness exists and is not simply material or instinctive satisfaction, but something more that we continue to dream about, without knowing exactly where we are going to find it. The Stoics used to say that absolute happiness is not to be found on this Earth, but nonetheless, we can find it, day by day, if we learn to search with perseverance, with patience, with discernment, knowing how to distinguish what is good for us from what is not.

There isn’t a single young person who doesn’t dream of freedom either, of the possibility of flying, because freedom for a young person is not about doing any old thing, but knowing what it is he wants to do, and where he wants to get to with what he is doing. There isn’t a single young person who doesn’t dream of that inner freedom for which there are no limits, for which not even death exists.

The big question we could now ask is whether there are still any young people left? Or are we doomed to see just children with adult faces? Is it not increasingly frightening to see in our little ones a look that is too deep for their age, or a seriousness that includes reproach, from the very first moments of their life? We also have adults dressed as teenagers who have not been able to overcome the anxieties of youth. It is necessary to overcome that perpetual duality in which young people, in particular, live, because they have to respond both to the functions of their animal instincts and to their more sublime dreams, conscious on the one hand that they are capable of achieving feats comparable to those found in great books, and on the other hand that they can also be beasts crawling on the ground.

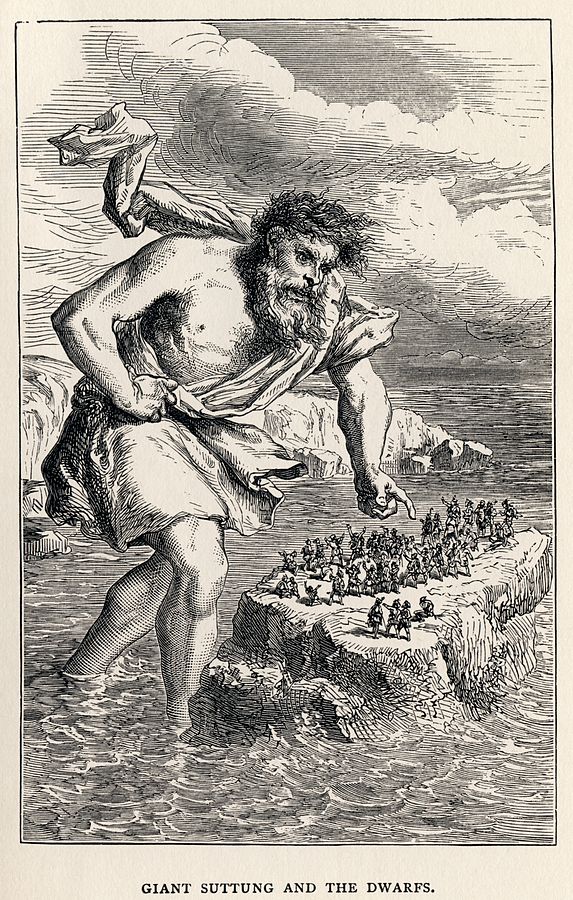

We must put an end to that struggle. But to put an end to a struggle, there is no other solution than to fight. In an old and sacred text from the ancient East – the Bhagavad Gita – there is an ideal man called Arjuna, who finds himself at the precise moment of this battle. He is just about to start fighting and has to make a decision there and then. He suffers desperately. Arjuna’s anguish 5,000 years ago however, is no different from the anguish seen in the current works on psychology: it is the same despair.

Arjuna has his whole animal and instinctive world on one side of him, while on the other side are all his sublime aspirations, the greatest and best part of himself. He has to decide, to choose, to break with the intermediate state, with instability; he has to pass the definitive test.

When, in ancient civilisations, young people were subjected to tests before being accepted as adults in society, there were good reasons for doing this. It was not just about the performance of empty rituals, but the undergoing of some special kinds of tests. They were the tests of “daring” and “deciding”; they were about the moment of battle, of choice, of putting discernment into practice. “Dare and you will surely be victorious”.

Within the mistakes that have pointed out as being the root causes of the anxieties of youth lie the answers that we are looking for. One only has to turn these mistakes around, give them an opposite meaning and turn them into solutions. Solutions of all kinds, from spiritual, intellectual, emotional, physical and biological solutions to real, practical and concrete solutions.

We have to remember something very important, and this is that, beyond all the anxieties that young people have, the greatest potentials are to be found in youth; and that, in order to be young, one doesn’t need to have a young body, for there is also an eternal youth, the Youth of the Soul, which has the ability to manifest itself whenever there is still the ability to dream and whenever there is still the ability to put those dreams into practice.

We should also remember that a person is young, eternally young and free from anxiety when, with dreams and the strength to hold on to those dreams, they learn to walk with a Torch, an old and familiar Torch that the human beings of yesterday, and those of today and those of all times, call Hope – the Hope of Youth, rather than the anxieties of youth.

Related posts:

Image References

www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/munch/ | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

Article References

Translation of the original article (Spanish)

What do you think?