Socrates

Article By Anonymous

The greatest of the philosophers was born in Alopeka, a town in Attica in the year 470 B.C. His father, Sophroniscus, was a sculptor and his mother, Phaenarete, a midwife – a profession to which Socrates often alluded, comparing it to his philosophical method, mayeutics (from the Greek maieuo, to cause to be born).

The greatest of the philosophers was born in Alopeka, a town in Attica in the year 470 B.C. His father, Sophroniscus, was a sculptor and his mother, Phaenarete, a midwife – a profession to which Socrates often alluded, comparing it to his philosophical method, mayeutics (from the Greek maieuo, to cause to be born).

He also learnt from his father the trade of the sculptor and was the reputed author of a work in marble entitled “the clothed Graces”, which stood on the Acropolis of Athens, as Diogenes Laertius informs us. He cultivated other arts, such as music and dance and it was said that he had helped Euripides to write his tragedies.

One of his teachers was Anaxagoras of Clazomenae, one of the most important philosophers of antiquity, who was also the teacher of Pericles. Another type of spiritual link – and a link with the Mysteries – occurred in 440 B.C. when he had the opportunity to meet the great priestess of the temple of Apollo, Diotima of Mantinaea, whom Pericles had asked to come to Athens to officiate at ceremonies of purification of the city, which had been affected by a plague epidemic. This meeting turned out to be decisive for the young Socrates, since the priestess initiated him into the mysteries of Eros, in the Orphic tradition, as Plato was later to show in a masterly way in his dialogue The Symposium, in which he introduced a passage about Diotima.

He was married twice, first to Xanthippe by whom he had a son, Lamprocles, and secondly to Myrtle by whom he had two sons, Sophroniscus and Menexenus. However, even in antiquity it was thought that he may have been married to the two women at the same time, since bigamy was permitted at a time when the city had been depopulated by wars and plagues. Xanthippe’s bad temper tested the spirit of the philosopher on numerous occasions.

He was a valiant soldier and took part in the battles of Potidaea, in 432 and Amphipolis in 422. The story is told that when the Athenians retreated, he did so walking backwards, so that he could continue to face the enemy. Apart from these journeys, he hardly ever left Athens; he only journeyed to Delphi, to the isthmus of Corinth and to Samos, where he met the physicist Archelaus.

The brilliance of his discourses and the admiration he aroused provoked the envy of two public figures: Anytus, an old provost of the city and Meletus, his young accomplice, who, offended by the irony of the philosopher, accused him of impiety. Lycon, the orator, was entrusted with the speech for the prosecution, which may have been written by the sophist Polycrates or by Anytus himself, who represented the artisans and magistrates of the people. Polyeuctus pronounced the sentence condemning him to drink the hemlock.

Proclus, in his commentary on Plato’s Cratylus, which deals with the meaning of names, asserts that the name of Socrates comes from sÛter tou kr·tou, which means: freer of the force of the soul and not being seduced by sensible things. And he attributes to him in addition a proverb which has been widely quoted: “beautiful things are difficult”.

Diogenes Laertius provides us with a great many testimonies gathered from among ancient authors and anecdotes, which illustrate the character of this philosopher: his resoluteness, his courage, the control over his passions, his austerity and his independence in the face of the rich and powerful.

Although he left no written works at all, the legacy left by Socrates can be described as gigantic, in addition to the example of a life dedicated to philosophy with extraordinary moral integrity. His disciples gave rise to schools, such as those founded by Plato and by Antisthenes the Cynic, major figures such as the historian Xenophon and the philosopher and orator Aeschines. The variety of viewpoints which is found among his followers negates the image of a closed and dogmatic Socrates, which has sometimes been attributed to him.

For Socrates, the fundamental knowledge is that which obeys the imperative inscribed on the oracle at Delphi: “Know thyself”.

Virtue and reason are in no way contradictory and philosophy is not a mere intellectual speculation, but a way of life. The Delphic oracle described him as “the wisest of men”, precisely because he recognised the limitations of human knowledge. His “I only know that I know nothing” is the recognition of those limits. Man is, then, the object of knowledge, and all that contributes to his happiness arises from an inner fullness and not from the enjoyment of external things.

The Socratic questions tear to pieces acquired knowledge and ignorance disguised as erudition, demonstrating that reason and virtue are not two contradictory concepts, since reasoning is indispensable for discovering the Good, the Beautiful and the Just. However, Socrates himself recognised the need for an even deeper and more personal form of knowledge, when he mentioned the inspiration he had from his daemon. This was the archetype of intuitive knowledge, in the Orphic manner of communication with the soul of the world, as moral conscience or inner illumination.

The death of Socrates, following his trial for impiety, was the last and crowning example of his philosophical life, and was narrated in full detail by Plato and Xenophon. The discourse he gave while drinking the hemlock, after saying goodbye to his closest disciples, was significantly represented by Plato at the end of his dialogue on the Soul, “Phaedo”, in which, in a symbolic-mythical framework, he deals with the theme of immortality, describing the regions of the afterlife in terms that prefigure Dante’s “Divine Comedy”.

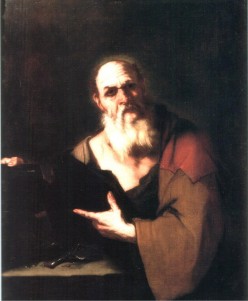

Image Credits: By http://caravaggio.com/preview/database/index.php?id=001095 | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By caravaggio.com/preview/database/index.php?id=001095 | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

What do you think?