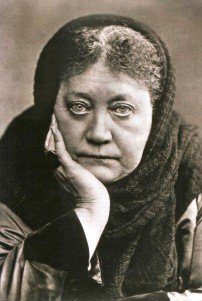

An interview with H. P. Blavatsky

Article By Jorge Angel Livraga

In the first few weeks of 1991 I found myself in London; I had come for one of my regular meetings with the principal representatives of New Acropolis in the UK and Ireland, who had travelled there for the same purpose.

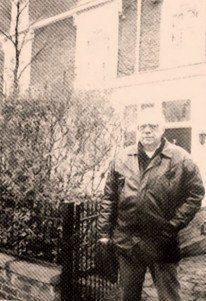

On a typical cold and rainy morning, I was visiting one of my regular haunts, Portobello market, with its thousands of antiques, curios and handicrafts. I remembered that we weren’t far from one of the last houses where Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (‘H.P.B.’) had lived and where she had written a large part of her monumental work, The Secret Doctrine. A taxi left us at the door of 17 Lansdowne Road, where the photograph that appears in this article was taken.

It was the atmosphere of the neighbourhood, more central than before, but still quiet and residential under that cold January drizzle, that suggested the idea of this article to me. It was an opportunity to go back a century in time and visit this house when its illustrious resident was still living there.

What follows, then, is fiction… or maybe not, at least not all of it. I’m not quite sure myself, as I’ve learned in life that fact and fiction are not always as separate as we might imagine.

In the School of Pythagoras, one of the tests faced by aspirants to the first degree (known as akousmatikoi) was to be presented with three black dots painted on a white background. When asked to describe what they saw, only those who answered ‘three black dots’ passed the test, while those who answered that they saw a triangle were disqualified. Associating things together through the use of the imagination -or more usually fantasy -is not always a virtue. Truth is more beautiful and more simple. And it doesn’t become easier to understand when it is over-explained. I leave it to the reader, then, to believe whatever he or she wants or is capable of believing.

* * *

A carriage dropped me off at the same door -No. 17 Lansdowne Road. The weather was wonderful and the sun -quite rare in London -shone brightly on all things.

I knew that Madame Blavatsky was expecting me and, realizing that I was a little early, I took my time to walk up the path before pulling on the brass handle that rang the doorbell. The door and facade seemed to have been freshly painted.

A lady, probably a servant, invited me into a tiny hall. I handed her my visiting card and, just before disappearing through a side door, she told me that I could go in, as Madame Blavatsky was expecting me. And there she was: the mythical figure of H.P.B. was seated in a wide working chair, at a desk in front of a large and very bright window. A number of tables, covered in loose manuscript pages and piles of typewritten sheets of paper, were ranged on either side of her. She looked very much like her familiar photographs, except that she seemed more human, more friendly and smiling. She was dressed very simply and her shoulders were covered by several dark shawls, bordered with fringes, some of which were coloured. Still smiling, she held out her hand, which was plump but with very soft and slender fingers. I greeted her and exchanged a few courtesies, explaining why I was there. Her eyes, large and protruding, disquietingly grey, looked at me curiously and a little mischievously. I think my nervousness, although I did my best to hide it, amused her. Picking up a thick and worn blue pencil, and making a gesture with her hand, she asked if I would be so kind as to wait in the room for a while, as she was just finishing off a sentence in the book she was writing, which was to be called The Secret Doctrineand would be much more extensive than Isis Unveiled.

The room was quite large -typical of the Victorian era -and I noticed many small tables and bookcases surrounding H.P.B. She appeared to be very ill with dropsy, which gave her once agile body an abnormal stoutness; she could barely rise from her chair. I saw her from behind, framed by the light that came in through the window, beyond which I could see the green of Holland Park.

The author in front of H.P. Blavatsky’s house at 17 Lansdowne Road, London

I walked around the room as quietly as I could. At the back of the room was a motley collection of books, parchments, rolls of cloth presumably containing writings, bronzes from India chosen more for their symbolism than for their antiquity or workmanship, Adoni tapestries, wooden dishes from Moradabad, tiles from Kashmir, Singhalese images, while the floor itself was covered with fibre mats from Palghat. Strange figurines that I couldn’t identify, pieces of rock, a few small fossils, gave the whole room an exotic appearance. There were souvenirs that had been picked up on journeys to faraway lands, which meant nothing to the casual visitor and would have looked more at home in the study of some adventurous old lord than in that of a lady of the Russian nobility.

I had not noticed that H.P.B.’s chair was of a revolving type and that she no longer had her back to me; she was looking at me in an amused manner, waiting for me to finish my inspection. Offering some excuse, I approached and sat down about six feet away from her on a wooden chair to which she gestured, next to a table that was only partially covered with papers.

Still smiling and without ceasing to look at me directly, she offered me a hand-rolled cigarette which I politely declined. She rolled one for herself and lit it with a long wooden match. A little cloud of smoke spread and the smell reminded me of the Turkish cigarettes that I was familiar with.

A female figure appeared from the right, dressed in grey and black. She approached us very respectfully and whispered something in H.P.B.’s ear.

‘The Countess is wondering whether you might like some tea,’ she ventured.

On hearing this, I felt embarrassed and quickly stood up, as I had assumed that this person was simply a maid. I accepted the offer, but before I had time to add some polite words, she disappeared into another room with a slight and gracious bow.

I once again felt the amused look of H.P.B. upon me, as she asked:

‘Did you think the lady who just came in was an elemental?’

Any harshness that the question might have implied was dispelled by her smile. But her grey eyes, the colour of mist, with their remarkably transparent pupils, left a deep impression on me. Meanwhile, I couldn’t help staring at a silver bell and remembering the strange phenomena that were said to occur in H.P.B.’s presence, involving so many remarkable incidents, including the ringing of a bell. Noticing my glance, she explained to me, amused as ever, that it was only to summon Constance, the Countess, if she needed her. She added that the distinguished lady was a good friend and an outstanding disciple-and not only of hers. Now she was also able to make contact with higher beings, if she were not so busy looking after her and attending to her at all hours.

‘Madam… please forgive my awkwardness. I have come to do an interview, but I don’t even know where to begin. Just knowing that the original manuscripts of The Secret Doctrineare lying here makes all my questions disappear.’

‘Well, calm yourself and drink your tea… I will have coffee,’ she said, pointing to the table on which I had been resting my arm a moment ago and which now had on it a complete silver service on a walnut tray, that must have been quite heavy, although I hadn’t noticed anyone putting it there and no one had come into the room. H.P.B. was no longer smiling and drew her coffee towards her. I didn’t want to be over-inquisitive, so I drank my tea, which was very hot and scented: Ceylon tea.

‘Seeing Countess Constance Wachtmeister here just now in such a humble attitude, and recalling the many noblemen and women, generals and scholars who have sought out your company, you seem to have a marked inclination towards people in the upper ranks of society. On the other hand, we know that you have offered your friendship and help to a great many people of humble origins, especially among the Hindus. Could you tell me something about this?’

‘I have also read some of the things you have written and it’s true that what has really evolved over the centuries is not man himself, but his machines, his vehicles and his means of communication; but there is something I invite you to reconsider if you want to understand the nineteenth century better. I was born in 1831 in a provincial city in Russia, more than half a century ago. There are aspects of the period I lived in which you have not taken into account; even in Central Europe more than half the population was illiterate and only a small minority had studied at university. The social and economic conditions were such that, with a few notable exceptions, being noble and well-educated were one and the same thing. Especially in the case of men, because we ladies were only required to be able to speak French, play a musical instrument and deal gracefully with some rather complex social rituals. At most, a few trips abroad or having some idea of painting was all that was necessary. Furthermore, books were printed in small editions and their costly bindings, in many cases, made them inaccessible to anyone living on a salary. As very few women could go to university, they had to take lessons at home and the scarcity of public libraries made having a private library in one’s castle, as my grandmother did, a great advantage. Believe me, humanity has made a lot of progress and will continue to do so in the twentieth century in that respect, at least in Europe, North America and in the major cities of the part of the world where you are from. If someone isn’t well educated today, it’s because they don’t want to be… but it wasn’t always like that.’

‘Nevertheless, you have praised the wisdom, and even the knowledge, of many Hindus.’

‘Yes… The situation in India in the middle of the nineteenth century was somewhat different, but essentially it was the same. The caste system enables a Brahmin, and even some Kshatriyas, to have contact with a higher culture. And the sages that I mention in my works are old monks who have access to incredible libraries or traditional teachings. My direct Teachers are princes, since over there, even a person’s physical race, their ancestry, is connected with their spiritual development. If you meet a porter who can read Sanskrit, for example, you can be sure that he is a disciple, a ‘lanoo’ on probation, and it’s highly likely that, until recently, he will have been living in a palace. Furthermore, in the days of my youth, slavery – and I’m not referring to the type regulated by Augustus – was a fact, from the United States of America to Russia. These people were living to survive and, regardless of whether they were happy or unhappy, the fact is that they had no time or inclination for the sciences, whether exoteric or esoteric. For them there were only beliefs, superstitions, traditional healing practices and so on.’

‘But you have been in contact with these credulous and simple people since you were a child, and you even seem to share their convictions. Am I wrong?’

‘Not entirely… But what was dogma and fanaticism for them, strongly influenced by ‘religious’ terror, was a motivation for me to study and gave me a direction in my researches into the occult.’

‘Madam, everyone knows you as H.P.B. I don’t wish to pry, but my readers often ask why you are called ‘Blavatsky’, which is the surname of a husband who could have been your grandfather and with whom you refused to live. I know that it isn’t for financial reasons, because when you took American citizenship you automatically renounced your substantial pension as the widow of a Russian general. Nor was it for reasons of social status, as you were born into the nobility and were related to the family of the Czar. So why Blavatsky?’

‘The truth is that, in my youth, I didn’t give the matter any importance. I married early in order to free myself from my family’s control and, to emphasize that, I took my husband’s name, which was the custom at the time. Afterwards, I got used to the name and initials, and it seemed to me disrespectful to the memory of the old gentleman to revert to my maiden name.’

‘Turning to another subject, you have attacked Spiritualism and your teaching about the ‘astral shells’ that torment mediums has become well-known. Why did you practise spiritualism yourself, despite the problems it brought you? And, were you yourself not in some way a kind of medium on certain occasions?’

‘In the middle of the nineteenth century, Spiritualism was an explosive phenomenon. This has happened at various times in history and even in the Old Testament those who practised such things were condemned. Summoning the spirits of the dead, or spirits which seek to pass themselves off as spirits of the dead, has always been the most popular and simplest way of replacing phenomena of a more ‘religious’ origin. The advance of Positivism and Materialism resulted in a weakening of all the known religions, including those in Asia; and some denominations, such as the Christians with their Inquisition and the corruption of the clergy, became so discredited that the ‘Hierarchy’ decided to encourage the Spiritualist movement as a way of providing temporary nourishment for people’s souls. I wasn’t attacking Spiritualism; I merely pointed out what it was and underlined the excesses into which it had fallen, often helped by the religions themselves. I could have been a good ‘medium’, and in a way I had been one in my childhood and my adolescence, but the presence of my Master was always with me and his powerful Servants protected me.

‘I must have been twenty years old when, as I was out walking one day with my father in Hyde Park, I saw my Master in the flesh, just as I had visualized him so many times in the Astral Light. I had always ‘felt’ that he was alive, that he was a real and embodied being, but it was quite a powerful experience for me to find out that it was actually true. When I saw him, he was surrounded by other Hindu dignitaries and when he noticed that I was about to approach him, he gave me a sign not to do so. I told my father everything, as by that time he was very supportive of me. The next day I returned alone to the same place and the Master was waiting for me. We walked in the park for a couple of hours and talked about many things.

‘Obviously I cannot repeat the details of our conversation, but it was mostly about me. He explained to me my strange characteristics, and why I had always been so different to others, and he gave me the reasons for all of this. He also spoke of the work I had to do in my present incarnation and especially of how to control my own powers and the world of the elementals and other invisible beings and strange forces that manifested in my presence. He gave me advice about journeys and people, books and… shall we leave it at that?’

‘Was it the Master K.H.?’

‘Excuse me… but would you give the name of your Master in a public article? There have already been too many misunderstandings, and storms of hatred and incomprehension have broken out because of information that has been leaked to the outside world. In our eagerness to spread this archaic form of philosophy which we call Theosophy, we gained many friends and caused a healthy stir in the fight against the darkness of obscurantism. But we also laid open to public scorn things that should have been respected and allowed the Sacred Books to be ridiculed, even though, fortunately, they are only published in fragmented forms and with many alterations. It was a time of great trials for me and, partly as a result of being unable to control my fits of nerves due to so many injustices, I am now so ill that I can barely feel the lower extremities of this poor body.’

‘Madam… I cannot help asking how H.P.B., with her extraordinary psychic powers and an exceptional capacity for concentration and mental development, was yet so vulnerable to the predictable attacks of people who were bound to act in this way due to their inherent natures and convictions?’

‘This is a very complex issue. I myself don’t know the answer exactly; but, to use a simile, think of a test tube in a chemical laboratory, in which reactions are taking place that release powerful waves of heat and other types of vibrations. The container will not always be able to resist the pressures; cracks and charring will begin to appear, the container will unconsciously start to self-destruct and may even burn those who are closest to it. But the Work had to be done… the athanor is not important. When it has finally broken up, it will turn to dust… I want my body to be cremated and my ashes scattered. The test tube is -how would you say it in the twentieth century? -contaminated.’

‘Tell us something about the Theosophical Society.’

‘You presumably know more about its development than I do. But I cannot and do not want to know any details about the future. Regarding the past I can say that, when I first travelled to Egypt, as a young woman, I made an attempt to found a kind of society or centre for the study of esoteric matters. Then, many years later, in New York, I met good old Olcott and we tried to do the same with the help of some very influential friends and a few other people who were simply curious. On the 17thof November 1875 we formed the Theosophical Society, which I helped found with my Master’s permission. Its principles changed in form several times because we were all a bit overwhelmed by our initial enthusiasm. However, on my Master’s advice, officially I was only the Corresponding Secretary, as it was expected that I would be doing a lot of travelling in the future. The real founder was Colonel Olcott, who, as you know, is a lawyer and an expert in psychic phenomena and spiritualism.

‘I know that without me the Theosophical Society would not have attracted the interest of so many people. Today there are three major centres of influence: the United States, England and India, where Adyar is, and maybe one day this will become its official capital internationally. For now, it is the headquarters more in name than in fact. But I also know that I have done much harm to the Society, because the attacks by religious and scientific fanatics have blackened its name and the names of many of its members, due to my own fault. I have never deceived anyone and have never needed to, because in my case it was always more a question of having to reduce the paranormal phenomena that I produced than any difficulty in producing them, which came naturally to me. But I was not skilful enough to know how to do things, to avoid the company of individuals who were driven mad by the effects of mediumship or simply by their own low spiritual stature, their envy and desire to stand out. At the moment, while writing The Secret Doctrineand correcting its proofs, I am also writing articles for The Theosophist and other Theosophical and scientific journals and have started to form what some people call the Blavatsky Lodge: an Inner Section, which is the real Esoteric School. I know that many of the people are not ready, but this is all I can do; I have to work with the human material available. Not to do it would be worse, although at times I have my doubts. My voices, which teach me so much, have fallen silent; my Astral Mirror reflects nothing. I obey and carry out what I have been ordered to do to the best of my abilities.

‘I have also been thinking about writing a Glossary of terms that could be useful for reading The Secret Doctrine. It will include many diagrams for teaching purposes that will also be added with time.’

‘For those of us who appreciate your extraordinary and superhuman work, it is especially upsetting that some of your time has been taken up with curious people wanting demonstrations of phenomena and private consultations. To enable you to finish your Work, I understand that the Masters have had to give you… some additional vitality. Why did you waste your energy on phenomena that served no real purpose?’

‘Forgive me, but everyone is entitled to live their life in the way they want or as best they can. Freedom is not about sheep voting for their shepherd, but something much deeper. It is something essentially individual and untransferable.’

‘I’m sorry… I didn’t mean to criticize your attitude. It’s just that many of us are sad that you have had to endure so much ingratitude and that, having created a worldwide movement, this is somehow dependent on friends or pupils whose only commitment is a personal bond with yourself.’

‘It’s a way of working which is not the same as yours, but it is mine. Any form of authority that is not firmly based on spiritual concord strikes me as ridiculous, and this is probably one of my many faults, but one’s own personality must inevitably play its part. But everyone is as they are, and what would life be without that authenticity? I may sometimes complain about it, but I love those long evenings of discussion about a thousand and one topics with people who don’t think in the same way as I do; and it’s very difficult for me to refuse someone when they ask me for something. I don’t believe that paranormal phenomena are of any importance, but they have been used since time immemorial. If you removed such phenomena from the Bible, for example, the Old Testament would be nothing more than an account of the trials and tribulations of a tribal group, and the New Testament would become a series of moralizing precepts like any of the writings of the Stoics. Paranormal phenomena are an ingredient that cannot be totally dispensed with. If they are genuine and are performed without any profit motive -although they are still very dangerous -people will remember them much more than any oral or written teachings, especially people who are afraid of life and death. And all of us, in some way, are afraid of certain aspects of this cycle of life and death. It’s not enough to remember past lives… as you yourself well know.’

‘Why don’t we remember anything of the periods between incarnations, when our consciousness is in Devachan, or Heaven, or whatever we prefer to call it?’

‘Because people try to remember with their mortal part, and with that part we can only remember our mortal existences. If we raise our consciousness to that part of ourselves which is not directly affected by destruction, we can obtain information about that Celestial Life that Plato and so many Initiates have spoken of… And now, if you will allow me, I must return to my work. It is slow… sometimes it takes two days before I can obtain some piece of information, a quotation, or a list of recently published books that I would never have time to read. Thank you for deciding to conduct this interview and for having taught your students that my works are not a ceiling, but a door. At all events, the future is looking difficult, and thinking about it is often frustrating. It’s better if we just get on with our work and don’t make long-term plans.’

‘Thank you, Madam, for existing, since that string which you said you have used to tie together the many flowers of wisdom has allowed us to understand a few true and meaningful things in the midst of the growing mass of empty words. And thank you for the tea, served so mysteriously…’

‘Perhaps in a few years’ time, the only thing that will be remembered about this interview will be the way the tea was served.’

H.P.B. laughed and seemed to be in an excellent mood, although I sensed that she was somewhat tired and her hands had mechanically returned to her papers. I said goodbye and got up. It felt as if only a few minutes had passed.

New visitors were being shown in at the door, as it was Saturday, and it seemed that the stream of visitors to Madame Blavatsky was as constant as ever, even if they were a select few. I couldn’t help smiling to myself and thinking that, deep down, H.P.B. would never change. She is a phenomenon; she knows it and has no desire to hide it.

The sun had begun to set and I walked slowly out into the darkness, clutching my notebook as if it were a treasure, which I would have to memorize in order to write up this interview.

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissions

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

Article References

This article appeared in issue 193 of the magazine ‘Nueva Acrópolis’ (Spain), in May 1991.

What do you think?