How do we know what we (think) we know?

Article By Florimond Krins

This is a question that Etienne Klein[1] asked his students when they were mocking people who thought the earth was flat. We know that the earth is round, an almost perfect sphere, it is a scientific fact. And it is easier to say that now as we have been to space and seen it. It is a different issue when we can’t see it physically and have to use our imagination. Looking at the curvature of the earth, observing the change of the sun’s shadows at different latitudes, or the movements of the stars and planets throughout the seasons, will give us clues and allow us to build an idea, a model of our planet and its shape.

This is a question that Etienne Klein[1] asked his students when they were mocking people who thought the earth was flat. We know that the earth is round, an almost perfect sphere, it is a scientific fact. And it is easier to say that now as we have been to space and seen it. It is a different issue when we can’t see it physically and have to use our imagination. Looking at the curvature of the earth, observing the change of the sun’s shadows at different latitudes, or the movements of the stars and planets throughout the seasons, will give us clues and allow us to build an idea, a model of our planet and its shape.

To start this process, we must ask ourselves questions, about our beliefs, our perceptions and habits. The things we do without thinking about them, the things our brain does almost effortlessly.

Gaston Bachelard[2] said that we must think against our brain, which sounds counter-intuitive. But what he means is that we must resist our first thoughts, the ones that come quickly and, one might say, without thinking.

For a lot of the stuff happening in our modern society, it is difficult to take the time to think and to study every subject. In most cases we listen to the words and thoughts of others, whom we call experts.

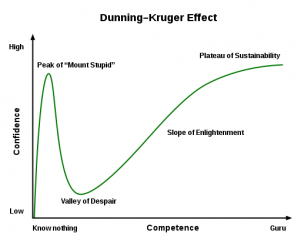

But not all experts are equal, and one can quickly fall into ultracrepidarianism[3]. When someone says: “I’m not an expert, but…”, everything that follows should be taken with a pinch of salt. The current pandemic is a good example of different people listening to a broad range of “experts” and “doing their own research”. It shows that information is tricky, and hard to convert into knowledge without making a few mistakes along the way. Something can happen when we discover a subject and have the illusion that we know enough to have a strong opinion about it: it is called the Dunning-Kruger effect, named after the two psychologists who discovered this phenomenon.

The Dunning-Kruger effect fades away the more you study the subject, the more you realise, as Socrates did, that you know nothing. Here we are talking more about consciousness than knowledge. Our capacity to be aware of our limits, our strengths and our weaknesses is something that should be worked on.

The Dunning-Kruger effect fades away the more you study the subject, the more you realise, as Socrates did, that you know nothing. Here we are talking more about consciousness than knowledge. Our capacity to be aware of our limits, our strengths and our weaknesses is something that should be worked on.

To be conscious of what we know and don’t know is the responsibility of the philosopher. To ask ourselves from time to time “How do you know what you think you know?” keeps us on our toes. We can’t possibly know all there is to know about everything, but we can have the humility to know when we are out of our depth. The quest for knowledge and our relation to it is a constant balance between conviction, doubt and faith. We have the right to ask any question and the power to make it our own journey. There is a true joy in discovering and unveiling the mysteries of Nature; it is what keeps us young at heart.

Image Credits: By Antonino Vara | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY 4.0, By 忍者猫 | Wikimedia Commons | CC0 1.0

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By Antonino Vara | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY 4.0

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

Article References

[1] Etienne Klein: French physicist and philosopher of science. [2] Gaston Bachelard (1884-1962): French philosopher of science. [3] The habit of giving opinions and advice on matters outside of one’s knowledge.

What do you think?