Plato

Article By Anonymous

The son of Ariston and a descendant of King Codrus and Perictione, who was a descendant of the great lawgiver, Solon, he was born in Athens in 429/28 B.C. and died in 347 B.C. His real name was in fact Aristocles and Plato was a nickname that means “broad-shouldered”. It was apparently given to him by Ariston, his wrestling teacher.

The son of Ariston and a descendant of King Codrus and Perictione, who was a descendant of the great lawgiver, Solon, he was born in Athens in 429/28 B.C. and died in 347 B.C. His real name was in fact Aristocles and Plato was a nickname that means “broad-shouldered”. It was apparently given to him by Ariston, his wrestling teacher.

According to Diogenes Laertius, he was born on the 7th day of Thargelion, which corresponds to the month of April, although the Neoplatonic Academy of Florence celebrated his anniversary on 7th November. He had two brothers, Adeimantus and Glaucon and a sister, Potona, who was the mother of Speusippus, his successor at the Academy. Little is known of his early youth, except that he cultivated wrestling, painting and composed dithyrambs, songs and tragedies.

His first philosophy teacher, according to Aristotle, was Cratylus, who in turn had been a follower of Heraclitus. At the age of twenty he met Socrates, who on the previous day had dreamt of a cygnet taking flight. He stayed with him until his master’s death, eight years in all. As he himself recalls in his Seventh Letter, as a young man he wanted to enter politics, desirous of taking part in public life in an age of decline and crisis for his city.

The trial and death of Socrates marked a turning point in the course of Plato’s life and a period of seeking and learning began. In this period he has been identified with some very significant philosophical schools and probably with some schools of initiation as well. He left Athens and moved to Megara, to hear the teachings of Euclid, and then to Cyrene, where he learnt mathematics with Theodorus. In Italy he became a disciple of the Pythagoreans, Philolaus and Eurytus.

The last stage of his journey took him to Egypt, where he fell seriously ill and was healed by priests who immersed him in the sea – although this may be a reference to a ritual alluding to his initiation in the Egyptian mysteries. On his return from Egypt he made his way back first to Cyrene and then to Magna Graecia, visiting Tarentum and Syracuse, two decisive cities in his biography. The first, governed by the Pythagorean Archytas, offered him the model for the government of the philosophers and the whole Pythagorean system, which was so essential to his philosophical work. It was Archytas, the philosophical prince, who put him in touch with Dionysius, the tyrant of Syracuse. A relationship was initiated with the tyrant Dionysius the Elder and his nephew Dion, full of vicissitudes, which ended with his being sold into slavery in Aegina and being freed by Anniceris of Cyrene. After his release, Plato returned to Athens and a long period of teaching and research began, which was to last some forty years, briefly interrupted by two journeys to Syracuse, in 366 and 361.

His philosophical school, the Academy, then came into being, in a modest gymnasium situated three kilometers from the Dipylon gate near the district of Colonus, where Sophocles had been born. Among the disciples of Plato, in addition to Speusippus as already mentioned and Aristotle, were two women: Lastenia of Mantineia and Axiotea, a Philasian, who dressed as a man.

Works

The writings of Plato take the form of dialogues or letters, characterized by an exquisite and refined style, designed to express in the most rational way the most abstract mysteries of knowledge. His philosophical arguments appear through the speeches of Socrates and other wise men, such as Timaeus the Pythagorean, who take part in his dialogues.

Among the many possible ways of cataloguing his thirty-five dialogues and thirteen letters that have been carried out by so many centuries of commentaries and followers of the Divine Plato, as he was called in the Renaissance, the chronological classification seems to be the one that bears most relation to the course of the philosopher’s life:

- Socratic period: Apology of Socrates, Crito, or Duty, Ion, or the Iliad, Laches, or Courage, Lysis, or Friendship, Charmides, or Temperance, Euthyphro, or Piety.

- Period of transition: Euthydemus, or the Arguer, Hippias Minor, or Falsity, Cratylus, or the Accuracy of Words, Hippias Major, or the Beautiful, Menexenus, or Funeral Orations, Gorgias, or Rhetoric, Republic I, or Justice, Protagoras, or the Sophists, Meno, or Virtue.

- Period of maturity: Phaedo, or the Soul, The Symposium, or Love, Republic II-X, or Justice, Phaedrus, or Beauty.

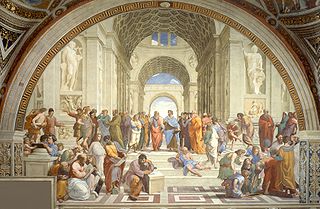

Period of old age: Parmenides, or the Ideas, Theaetetus, or Knowledge, Timaeus, or Nature, The Sophist, or Being, The Statesman, or Royalty, Philebus, or Pleasure, Critias, or Atlantis, The Laws, or Legislation, and Epinomis, or the Philosopher. - In the allegorical fresco of Philosophy painted by Raphael of Urbino and entitled “The School of Athens”, Plato appears holding the text of the Timaeus, thus referring to the most significant work of Platonic philosophy, which has been one of the most studied throughout the centuries, and is full of Pythagorean references and a wisdom originating in the Mysteries concerning the doctrine of the World Soul.

Plato and philosophy

It can be affirmed that Plato transposes the mystery tradition into philosophy, as can be seen from his use of the concepts of reminiscence and purification. In this respect he sets out two principles: that of the progressive transmutation of being as the sensible world rises towards the intelligible world, and that of Theophany or the union of the soul with the divine. See the Symposium and the account given of the teachings of Diotima.

The Platonic philosopher is like Eros, the son of Poros and Penia. Only the gods are wise. The philosopher stands midway between wisdom and ignorance, because he is conscious of his ignorance. In the Symposium, the definition of philosophy is given as love or desire for wisdom. The philosopher is not only an intermediary, but also a mediator, since he reveals to men something that proceeds from the world of the gods, from the world of wisdom. Philosophy, in the Symposium, appears as an experience of love. “Wisdom is one of the most beautiful things and Love is love for the beautiful, so Love must be a philosopher and must therefore lie midway between the wise and the ignorant”, he declares in the above-mentioned dialogue, through the mouth of Socrates. Philosophers are, like Love, intermediaries between the gods and men. Love is the aspiration of men to happiness. It is the desire for immortality, the impulse of intelligence towards the idea of the Good. Philosophy is also an exercise in dying, since death is the separation of the soul from the body, which is what the philosopher strives to achieve. The philosopher is one who truly knows the science of dying.

In the Theaetetus he describes the way of life of the philosopher, which lies in becoming just and holy in the clarity of intelligence. Knowledge for Plato is never theoretical: it is the transformation of being, virtue, as well as feeling. In his dialogue, Parmenides, he speaks of the relationship between ideas and things. Plato speaks of the participation of things in Ideas. He reconciles such a principle by saying that what exists, reality, is neither pure unity nor pure multiplicity.

The doctrine of the Ideas is the central core of the Platonic philosophy, as well as being the aspect most disputed by Aristotle and his followers. The ideas are the truth of things, the essences that sustain reality, and the models that govern the cosmos. The soul can gain access to the ideas, once it has been freed from the conditioning of the sensible world and discovers that perceptible reality is no more than the shadow of the ideas. The interpretation of the relationship between ideas and things has led to the question of whether Plato is defending immanency or a transcendent position that separates essences from things, although in effect he reconciles these two apparently antagonistic interpretations.

Image Credits: en.wikipedia.org

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

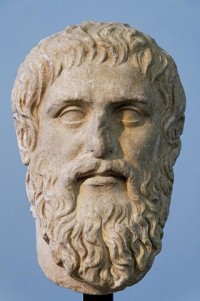

"Plato Silanion Musei Capitolini MC1377" by English: Copy of Silanion - Marie-Lan Nguyen (User:Jastrow) 2009. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons - commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Plato_Silanion_Musei_Capitolini_MC1377.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Plato_Silanion_Musei_Capitolini_MC1377.jpg

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

What do you think?