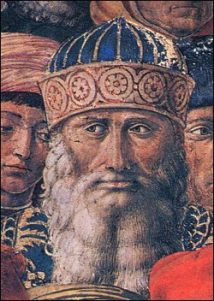

Plethon

Article By Anonymous

He was born between 1355 and 1360 in Constantinople. Although we have no definite information about his family or origins, the various authors who have researched the subject believe that he was born into a well-to-do family, probably of an orthodox priestly origin, so it is logical to suppose that he received a complete education from his childhood onwards.

He was born between 1355 and 1360 in Constantinople. Although we have no definite information about his family or origins, the various authors who have researched the subject believe that he was born into a well-to-do family, probably of an orthodox priestly origin, so it is logical to suppose that he received a complete education from his childhood onwards.

The fact that the Turkish Empire was in the ascendant at the time, conquering territories which until then had been under the influence of Byzantium, meant that many Greek intellectuals moved to the Sultan’s court. So it was, according to Scholarios, that, on an uncertain date, Plethon travelled to at least two of the most important cities in the area, Adrianopolis and Brusa, with the intention of studying with Eliseus, a Jewish adept in Falsafa, who was in contact with Jews from Spain and was versed in the writings of Averroes and Maimonides. It was Eliseus who brought Plethon into contact with the doctrines of Zoroaster, which exerted a decisive influence over his thought. It is from this period that his Treatise on the Chaldean Oracles and, in general, his interest in and study of Islam is believed to originate.

At the beginning of the 15th century, in that period of calm in the relations between Turks and Byzantines, which occurred after the defeat of the former by Tamerlane at the battle of Angara (1402) and then the peaceful reign of Mehmed I (1413-1421), Plethon returned to Constantinople, where he rapidly acquired great fame as a scholar and gathered around him a circle of disciples, notable among whom was Markos Eugenikos, who was to fulfill an important role at the Council of Florence.

The Church’s alarm at the content of his teaching led to Plethon being expelled, and in 1409 we find him in Mistra, a city near ancient Sparta, which, still under Byzantine rule, was the only stable place in the area. Little by little it became a cosmopolitan city where there was to be more freedom of thought than in the capital of the empire itself. There, under the protection of the emperor, who even presented him with land and fortresses, Plethon developed his school, which was later to become so important for the diffusion of Platonism in the West.

Between 1438 and 1439 Plethon journeyed to Italy with the Greek delegation to take part in the Council which hoped to win the aid of the European princes for a Constantinople increasingly surrounded by the Turkish forces, and also to achieve the union of the Orthodox and Catholic churches. Although neither of these two objects was achieved, the contribution of Greek and Oriental philosophy to the enlightened circles of Florence was notably strengthened.

Gemistus Plethon served mainly as a consultant to the Greek ecclesiastics in the fields of theology and philosophy. In Florence he came into contact with the circle of Leonardi Bruni, the heir to the teachings of Petrarch and translator of Plato, and initiated a relationship and a marked influence over Cosimo de Medici with regard to the need to go more deeply into Hellenic thought, bypassing the interpretations of St. Augustine which were fashionable in Italy at the time.

“The great Cosimo would frequently… at the time when the Council was in progress between the Greeks and Latins… listen to the discourses of a Greek philosopher called Gemistus, surnamed Plethon, who was almost another Plato. His fervent speech immediately inspired him, to such an extent that he conceived the idea of an academy which was to be founded at the earliest opportunity”, declared Marsilio Ficino, in the Preface to his translation of Plotinus.

Gemistus Plethon was appointed by Cosimo de Medici to the chair of philosophy in Florence, and one of his students was Bessarion, who later became a cardinal. After the Council, Plethon returned to Mistra in 1440, which he never again left and where he died on 26 June 1452. After his death his main work was discovered, the Code of Laws, which he may possibly have been writing throughout his life and which was requisitioned and hidden by Demetrius, Prince of the Peloponnesus.

After the capture by the Turks in 1460 of this last bastion of the extinct Byzantine Empire, the work was taken to Constantinople, where the Orthodox Patriarch, Georgios Scholarios, after several vicissitudes that revealed the lack of unanimity on the matter among the Greek clergy, destroyed part of it, considering it to be heretical and pernicious. Fifteen chapters plus the general index remain of the text which, judging from the number of copies which have been found throughout numerous European libraries -Vienna, Madrid, Paris, Naples, Florence – gives an indication of how widespread Plethon’s thought was among renaissance thinkers.

His work

He made extracts from and commented the works of Appian, Theophrastus, Aristotle, Diodorus Siculus, Xenophon, Porphyry and Dionysius of Halicarnassus. He wrote works on theology, music, rhetoric, funeral orations, history and treatises on geography. His work “De gestis graecorum post pugnam ad Mantineam”, based on Diodorus and Plutarch, was published in Venice in 1503 and numerous editions were published in several languages.

Other works: “De rebus Peloponesiacis constituendis”; “Oracula magica Zoroastris”; Prolegomena Artis Rhetoricae”; “Orationes funebres de inmortalitate animae”; the treatises “Zoroastri et Platonicorum dogmatum compendium”; “De fato”; “De virtutibus”; “De legibus” and, most importantly, “De Platonicae atque Aristotelicae Philosophiae differentia”, which clearly reveals his Neoplatonic orientation and openly exalts Plato to the detriment of Aristotle. It was this that drew down upon him the wrath of recalcitrant Aristotelians such as Georgios Scholarios, the Patriarch of Constantinople, who ordered the destruction of his “Code of Laws”.

He attempted to reconcile the eastern theogonies with the doctrines of Christianity. In moral philosophy he was influenced by Stoicism. For Plethon, Zoroaster was the most ancient source of wisdom, and his genealogy ended with Pythagoras and Plato.

The “Chaldean Oracles” were the pristine source of the wisdom of Zoroaster, and this work was considered to be contemporaneous with the texts of Hermes Trismegistus, although, in reality, it was written in the 2nd century A.D. in the age of Marcus Aurelius. W. Kroll published the work in 1894. The index of the “Code of Laws” that has been preserved and his numerous writings on politics, history, medicine, music, metaphysics and philosophy, reveal Plethon’s intention to restore philosophy as a way of life capable of harmonizing the individual and society with a transcendent purpose for which the gods have placed us in this world.

Plethon traced a detailed line of predecessors in the doctrines, which he summarized, going from Zoroaster and the Hindu brahmins, through Pythagoras and Plato, to Plotinus and his disciples, Porphyry and Iamblichus. He made it clear that in the most important matters, such as knowledge of the gods and the origin and destiny of man and the world in general, he was not introducing any innovations. “All these [philosophers] agreed on the majority of the most important matters and always seem to have revealed their ideas to the most intelligent men”, says the philosopher in the Code. He was therefore careful to remove from his synthesis the relativistic Skeptics and the Sophists, both of classical and modern times. Thus, for example, Chapter III of the Code of Laws is dedicated to a refutation of the doctrines of Protagoras and Pyrrhon.

With regard to the nature of men, Plethon stated that this is dual, since it consists of an immortal and eternal part, of the same nature as that of the gods themselves, and another animal-like and temporal part, claiming in this to be following the teachings of Zoroaster, Pythagoras and Plato. He calls man that being who combines in himself two opposite things, matter and spirit, a necessary condition for a universe “gathered into a structured whole”. Thus, in man are mixed the mortal and the immortal, a necessary meeting point for the harmonization of these opposing constituents of the world.

His aim being to recreate Philosophy in its full sense as a way of life, as an indispensable practice for bringing about an improvement in the human being and, in consequence, in society, Plethon reproduced in Mistra what Plotinus achieved in Alexandria, with his teachings and his philosophical movement.

Image Credits: By http://www.ritosimbolico.net/studi2/studi2061.jpg | Wikimedia Commons | CC BYPD

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By www.ritosimbolico.net/studi2/studi2061.jpg | Wikimedia Commons | CC BYPD

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

There is a wrong letter in “The Battle of Angara”. It should be “The Battle of Ankara” or “Battle of Angora”. BTW, concise article 🙂