Raphael: The Drawings

Article By Siobhan Farrar

Raphael was born in 1483 and by the age of 17 he had been given the title of ‘Magister’, meaning independent master. This exhibition of his drawings and studies at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford takes a look at the essence of the artist. The opening lines of the exhibition’s guide read as follows:

Raphael was born in 1483 and by the age of 17 he had been given the title of ‘Magister’, meaning independent master. This exhibition of his drawings and studies at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford takes a look at the essence of the artist. The opening lines of the exhibition’s guide read as follows:

’Drawing drove Raphael’s creativity. Whether tentatively sketching or moving with inspired conviction, Raphael’s hand generated lines that gave shape to his pursuit of eloquent forms.’

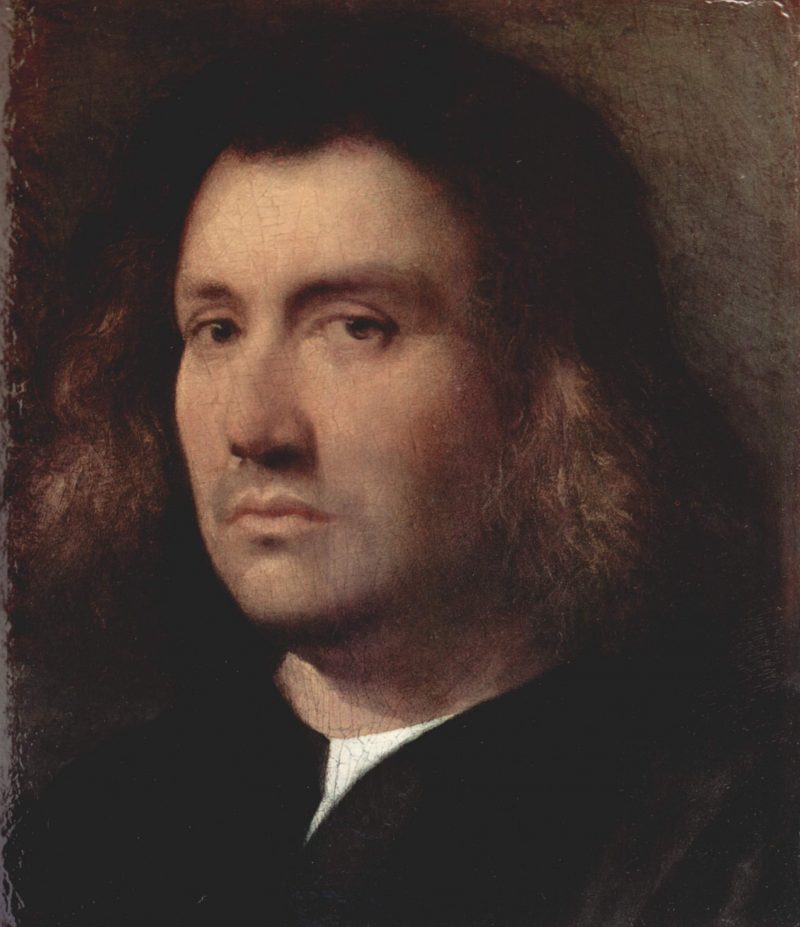

Opening with his ‘Portrait of a Youth’, a likely self-portrait made in 1500 possibly upon receiving his title of Magister, we see a serene confidence and the luminous potential of a life shining through simple black chalk on paper.

His ability to accurately convey vast swathes of subtle human emotions is continuously reiterated in his drawings and none of it is contained in any one detail alone. Often the expressions are only faintly suggested with simple marks, yet in the whole composition he is able to bring to the imagination impressions of subtle and complex aspects of human life.

‘Raphael uses drawing as a means of observation, as a mode of expression and as a way of reflecting on human emotions and actions.’

In the sketch ‘The Virgin with the Pomegranate’ the mother looks lovingly over the Christ child as he reaches for the fruit, her expression radiating warm divine love but with a sombre acceptance of the challenges that the child will face. There is a complex truth common to the human experience in this image, motherly love accompanied with the anguish of knowing the inevitable difficulties that come with life, as well as the necessity for all children to move from the security of their mothers.

In 1508 Raphael moved to Rome where he went on to work on his great commissions for the Vatican, in which he refined his concepts of philosophy and theology while searching for ways to depict compelling visual narratives. In ‘The School of Athens’ each philosopher is given a distinct character, showing both Raphael’s likely deep reflection upon the ideas of the philosophers themselves as well his expert depiction of inner poise, through external gesture. Raphael would have been very familiar with the culture of oratory in Rome and the importance of facial expression and gesture of hand.

In one study of the Christ figure from ‘La Disputa’, the weight of the fabric covering the lower part of Christ appears almost statuesque and permanent like marble, whilst the upper body dissolves and is enveloped in an ethereal divine light, achieved through the blank spaces left by Raphael and the barely traceable white ink that draws out further luminosity.

A term used by Raphael and others during the Renaissance is Disegno, which means both design and art: the artist is not describing ideas, but is designing the most perfect expression for them.

‘Raphael’s eloquence in drawing is based upon deep reflection and on the intelligence of his hand.’

Raphael shows us something of human nature and human potential: a reflection of the natural complexities of life that evade expression in words.

Image Credits: By Fae | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By Fae | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

What do you think?