The Gurukul Tradition of Ancient India

Article By Manjula Nanavati

Indian philosophy holds that the universe is not confined to what is apparent to our sense perceptions, and that the Ultimate Reality is veiled from us, by a curtain that maroons us in ignorance and illusion. Accordingly, the main purpose of education in ancient India was to pierce this curtain in order to experience the realization of what lies beyond what the mind infers through the physical sense organs, and to develop the mind to become a suitable channel to aid, rather than hinder, this process.

Indian philosophy holds that the universe is not confined to what is apparent to our sense perceptions, and that the Ultimate Reality is veiled from us, by a curtain that maroons us in ignorance and illusion. Accordingly, the main purpose of education in ancient India was to pierce this curtain in order to experience the realization of what lies beyond what the mind infers through the physical sense organs, and to develop the mind to become a suitable channel to aid, rather than hinder, this process.

Learning was therefore, a sacred duty, prized and pursued not as an accumulation of theoretical knowledge, but as a means of self-realization.

One of the platforms through which this unique concept of education was disseminated was through the ancient Indian Gurukul tradition. The term Gurukul comes from Guru, meaning teacher and kul, meaning extended family or home. All pupils left their parental home and were assimilated into the Guru’s household for the entire duration of their schooling. The commencement of this crucial phase in a child’s life was sanctified by a ceremony at the age of about 8, signifying a new birth. From that moment on, the Guru took complete responsibility for the pupil who was known as Dvija, or twice-born.

The Guru determined the course of study and its schedule of delivery, from a diverse and comprehensive curriculum: the knowledge of the 4 Vedas and Upanishads, Mathematics, Economics, Astrology, Language and Grammar, Dialectics, Theology, Politics, Military Science, Fine Arts, Medicine, Yoga, Martial arts, Archery. (1) In addition, where appropriate, vocational skills were taught and apprenticeships undertaken. The emphasis was always on helping each student evolve the strengths that would sustain him through the challenges of life, whether hardship or kingship, and each student progressed at his own pace as assessed by the Guru. Continued acceptance depended on the pupil demonstrating steadfast discipline, unimpeachable conduct and irreproachable moral strength. No fees were exchanged, nor was there a specified duration of study. Instead, when the Guru indicated that the student was ready to leave, a gift of homage was customarily offered as Guru dakshina.

Integral to this structure was the active part students were expected to take in the chores that supported the hermitage. The first duty of the day was to collect firewood to keep the sacred fire burning, symbolic of enkindling the mind. It was quite customary for a pupil seeking acceptance to approach the Guru with a bundle of firewood in his arms, signifying his willingness and allegiance. Other assignments included common domestic tasks, always designed to purify the ego and promote self-reliance. These hermitages were often secluded deep in the midst of nature, where the sylvan solitude encouraged the flowering of a connection between Man and the Earth. Class routines and tasks coincided with the cycles of nature emphasizing the idea of man as an intricate part of the web of life. (2)

The Guru imparted not only his knowledge but his values, ethics and the way of life. This close and intimate relationship built between Guru and Shishya became a sacred bond and a vital hallmark of Gurukul education, enabling the student to imbibe intangible elements too subtle to be articulated: the teacher’s deep-rooted attitudes, his innate intentions, the essence of his methods and the spirit of his life and work.

Because the heart of this system was the teacher, pupils belonged not to the abstraction of an institution, but to the Guru, who was accorded worshipful respect, as exemplified in the epics, literature, and poetry. Many shlokas of the Vedas deified the teacher, as Acharya Devo Bhava (Taittiriya Upanishad), acknowledging them as living repositories of preserved knowledge, tradition, culture, and insight.

For thousands of years this legacy was transmitted through the oral tradition, in the Guruparamparya system of a succession of pupils and teachers forming an unbroken chain through the generations. Even up to the 8th century AD it was considered sacrilege to reduce the Vedas to writing, for education was not recognized as merely the ability to read, write and understand, but something to be realized and assimilated as an organic part of oneself. Accordingly, the Gurukuls employed a unique method of teaching that, as mentioned in the Upanishads, consisted of 3 steps. (1)

SRAVANA was the process of listening to the words of the teacher. The medium of the Vedas was the sutra a condensed sentence or verse, compressed with meaning and open to interpretation. Additionally, it was considered that sound itself carried power, so that the sound and rhythm of the verse, and the ensuing vibration, carried potency and meaning to be directly internalized.

MANANA, the next step, was a process of deliberation and reflection on the subject, comprising discussion, debate and arguments as a big part of the process. However, this would merely result in intellectual understanding and reasoned conviction. Only the third step could complete the process required for true learning.

NIDIDHYANASANA is the realization of the Truth through meditation. The Upanishads describe preliminary exercises for training in contemplation called Upasanas, which if practised rigorously would lead to the “consciousness of the One, undisturbed by the slightest consciousness of the many”. (1)

With this as the foremost objective, the study of the subjects became but different vehicles for perceiving the truth. Its focus was on the principle of knowing, rather than knowledge; of perceiving the truth, rather than mere logical understanding of it, and its method was Yoga: “the art and science of the construction of the self through discipline and meditation.” (1)

Education then was the training of controlling the mind, so as to be able to dive deep into the depths of our inner awareness, while remaining unaffected by the allure or aversions of the illusive, material world. It was a source of illumination.

The Gurukul system slowly became firmly entrenched all over India due to the support provided by the kingdom, in accordance with ancient practise. Thus upkeep, the feeding and clothing of pupils, and the Guru’s requirements were all adequately commissioned, ensuring that even families with very little means were able to send their children to a Gurukul. This vibrant tradition continued to flourish even alongside India’s widely celebrated and prestigious universities of higher learning. Takshila founded in 1000 BCE, and Nalanda founded in 500 AD, amongst many others, attracted scholars from all over the world, who braved the dangers of arduous travel, for the privilege of studying under highly revered teachers and sages of the time.

By 1830 when the British commissioned its collectors to collate data on the number and type of education offered through the subcontinent, Thomas Munro reported that “there were 1,00,000 village schools in Bengal and Bihar alone. The epics, reading, writing, arithmetic and more were being taught”. (2) Surveyor William Adams has written that “he could not recollect studying in his village school in Scotland anything that had more direct bearing upon daily life than what was taught in the humbler village schools of Bengal.”(2) These reports spoke of dedicated teachers, a method of imparting knowledge without violence, and high attendance all round.

However, with the Colonial patronage of the founding of schools expressly to provide a western education to a cadre of Indian clerks required to run the British bureaucracy, and the withdrawal of the grants that supported indigenous education, this unique vernacular legacy began to slowly disintegrate. (3)

Today, in most institutions of academic excellence all over the world, the terms holistic education, experiential learning, student-centric instruction and transformational education are thrust forward as modern and progressive methods. But these very concepts were already the heart of the Gurukul system that took root in India around 5000 BCE. Unfortunately, however, in a consumerist society, education runs the risk of becoming a product, with coaching class ‘gurus’ selling a service for a fee, to stressed students and their anxious and often overburdened parents. It is evident that the role of a teacher as a lamplighter of Truth has been devalued, and many reputed schools and colleges are seen as primarily hunting-grounds for human resources to feed international corporate empires.

Is there a balance to be found between these two contrasting ideologies that might be better suited for our future? Dare we imagine an innovative and open-minded approach? I suggest that we must… for a society that loses its teachers, loses itself. If the core purpose of education must once more be oriented toward discovering the true meaning of being human, perhaps pupils at all scholarly institutions today, and society at large, would have much to gain from a hybrid system that could combine modern infrastructure and technological teaching aids, with some of the age old principles of the venerable Gurukul tradition: one that upheld the value of forging an ethical life above worldly success, strengthened the sacred connection between man and nature, instilled the value of the preservation of a cultural heritage, and encouraged the blossoming of a spiritual awareness, that helped to lift the veil, to experience glimpses of the eternal, infinite Truth.

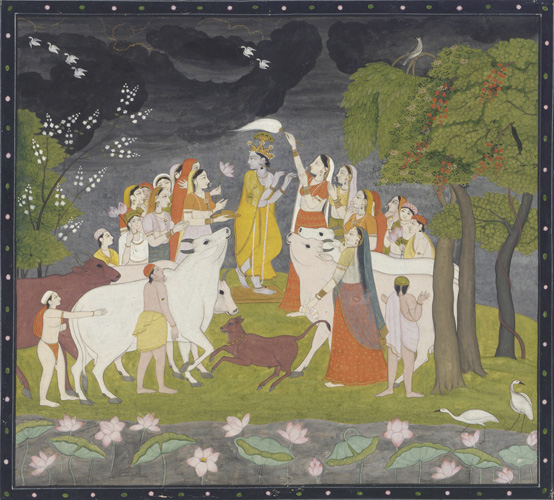

Image Credits: By Neesha Thunga K | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 4.0

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By Neesha Thunga K | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 4.0

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

Article References

1. Radha Kumad Mookerji. Ancient Indian education. Motilal Banarsi Dass Publishers. Delhi. (2016). 2. Sahana Singh. The Educational Heritage of Ancient India. How an ecosystem of learning was laid to waste. Notion Press. Chennai. (2017) 3. Dharampal. Collected Writings Volume 3.The Beautiful Tree. Indigenous Indian Education in the Eighteenth century. Other India Press. Goa. (2000)

What do you think?