The Magical Function of Rituals and Ceremonies

Article By Julian Scott

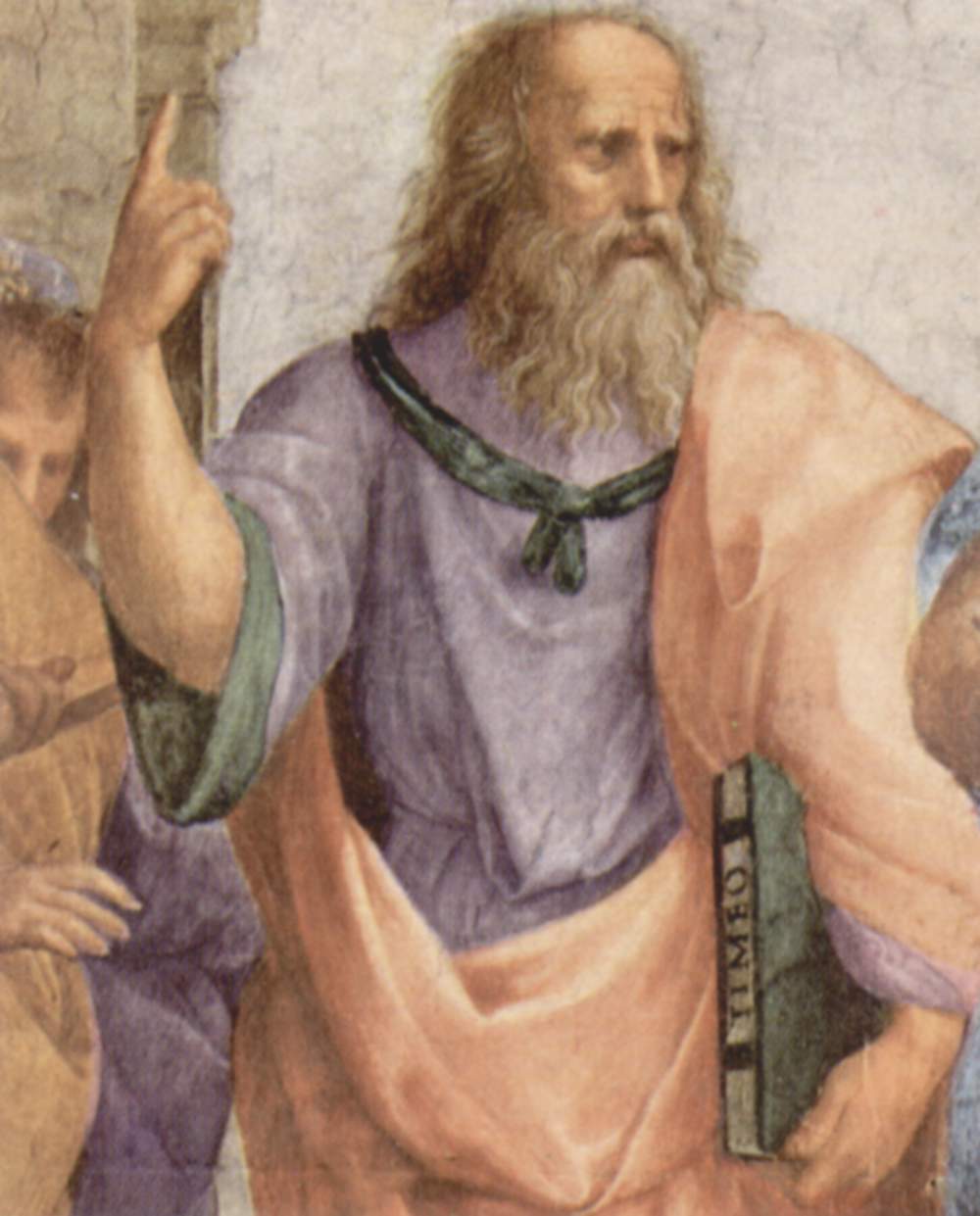

From an esoteric point of view, a ritual is dependent on the existence of the invisible dimension. This invisible dimension consists of a spiritual-mental aspect, which is the domain of the archetypes or ‘living idea-beings’ spoken of by the Platonists; and an ‘astral’ aspect, which is an intermediate world between spirit and matter, just as imagination is the link between the world of ideas and the physical world. In this view of things, the invisible world exists, the material world reflects. The visible is the shadow of the invisible.

A ritual or ceremony is a re-enactment of the creation of the world , an opportunity to connect with the creative forces of the origins and so to begin again, to regenerate oneself and to emerge renewed. An example of this is the rite of baptism, which is to be immersed in the primordial waters, to suffer the Deluge and to re-emerge on the primordial mound of a new creation. Another way of looking at the ritual is to see it as a door to the invisible dimension, a means of access to the sacred. And this is why rituals are necessary, because the invisible is by its very nature difficult for us to access, prisoners as we are of flesh and matter. So we need special tools and devices to help us reach it. These tools are symbols, myths and rituals.

In the ritual, material elements play an important part. They are the vehicles through which the invisible can become manifest and the consciousness can ascend to a more exalted state than its usual mundane condition. These elements are, by way of example: sound, movement, aromas, postures, gestures, as well as ritual objects, statues and images. The power of the spoken word is of great importance in any ritual, for example in the reciting aloud of a prayer. As H.P. Blavatsky explains in the first volume of The Secret Doctrine: “… the spoken word has a potency unknown to, unsuspected and disbelieved in, by the modern ‘sages’… and such or another vibration in the air is sure to awaken corresponding powers…”

A prayer, in the philosophical sense, is not asking some god for a special favour, but is a means of offering the best part of oneself to something higher; it expresses an aspiration to become better, nobler, greater, to express the very highest part of ourselves. If the essence of that prayer is not somehow expressed in the actions of our everyday life, however, it has little or no value. The reciting of it in a ritual, alongside other aspiring human beings, reinforces our daily efforts, takes its power from our successes and our failures, and then feeds back into our daily existence. Perhaps this prayer will elicit a response from the invisible world, for, as the ancient Egyptians believed, the human being will receive the unconditional support of the Gods if he acts with justice and wisdom. The whole ceremony itself is a prayer in action – a way of connecting with the archetypal world and bringing it into action.

Music, as the harmonious expression of sound, has always played a central role in ceremonies everywhere. Mozart famously composed music for Freemasonic ceremonies and Pythagoras is said to have used it in the ceremonies conducted at his school in Crotona. Movement includes ritual postures and gestures, as well as the use of the directions of space: the four cardinal directions plus the nadir and zenith. For example, pointing up or down with the hand, turning to the left or the right, walking clockwise or anti-clockwise, etc.

For the current mentality, to give importance to such things is often considered ‘mumbo-jumbo’. But in all symbolic traditions, the cardinal points have particular meanings. To take the simplest example, east symbolises sunrise (birth) while west represents sunset (death). Hence in the Egyptian city of Thebes (modern Luxor), the tombs were all constructed on the west bank of the Nile, where the sun sets over the Western Mountain. Newgrange in Ireland and Stonehenge in England face the east, so that the rising sun of the solstice can strike a particular point in the temple and bring enlightenment and renewal to participants in the rituals.

Is this all just fantasy and imagination? Fantasy, no; imagination, yes. For imagination is the capacity to symbolise and to connect with what the symbol (image) represents – its Being. The sun in this world represents another sun in the invisible world: God or the Great Spirit. The four directions are living symbols of the four great powers that, in some traditions, are said to govern the Cosmos.

Think of the knight who kneels in a gesture of humility, to be touched by the sword, symbol of justice, will and spiritual awakening, and then makes his oath to uphold justice and protect the weak against the strong. In this ceremony we have a posture, a gesture, a prayer (the spoken word) and a ritual object. In India we find a whole system of asanas (postures) and mudras (ritual gestures) which reflect the same importance given to these elements.

Other universal ritual objects are shells – symbols of birth and rebirth – used either as receptacles for the waters of life or, in the case of conches, as trumpet-like instruments to awaken the soul from its lethargy, dozing away in the folds of matter: a call to battle, to new life instead of stagnation.

In ancient Egypt, the land of magical rituals par excellence, we find the Was sceptre, a magical staff with the head of the god Set. Set is the instigator of chaos and confusion. By placing his head at the top of this magical staff, it is transformed into a powerful instrument of renewal and strength .

No ceremony would be complete without some special aromas, which evoke certain subtle and higher feelings. Frankincense, myrrh and sandalwood are some universal examples. Many people will be familiar with aromatherapy and may have experienced first-hand the power of aromas to induce certain psychological states. We can also think of their opposites – unpleasant smells – and how these bring the consciousness down to a lower physical level.

The French occultist Éliphas Lévi remarks in one of his books that the ceremony does not make the magician; the magician makes the ceremony. Without needing to be a magician, it is true that it is the participant in the ritual who must bring their own being into it; who must come not as a supplicant, but as an offeror, a ‘sacrificer’ (one who makes sacred), without looking for any reward. As Confucius knew well, a ritual performed automatically is useless, because where there is no consciousness there is no elevation. Perhaps it is even worse than useless, because to do something sacred mechanically degrades and corrodes the Soul.

Image Credits: By Abishek Photographer | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 4.0

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By Abishek Photographer | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 4.0

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

Article References

1. My Heart My Mother – Death and Rebirth in Ancient Egypt, by Alison Roberts 2. The Magical Ritual of the Sanctum Regnum

I’m seriously interested on the invisible world and Plato’s theory of epistemic ascendance. However by riding Plato’s writings on the subject through the lenses of Parmenides teachings on opinions I came to the conclusion, that even to date, for the so-called prisoners of the cave the invisible world remains a subject matter of an unbearable gravity.