Architecting the Invisible

Article By Kurush Dordi

When architects design a building in our times, they share the plan of a proposed building and get the client to approve its design, based on which the building is then taken up for construction. But how do you design a building when your client is divine, or in the invisible?

When architects design a building in our times, they share the plan of a proposed building and get the client to approve its design, based on which the building is then taken up for construction. But how do you design a building when your client is divine, or in the invisible?

In spite of magnificent palaces, beautiful gardens, and colossal libraries from the ancient world, sacred sites have most often been considered the epitome of man’s architectural achievements. Perhaps there is something unsaid in the sentiment of ancient sacred structures, which never fails to inspire, inviting us to get lost in their splendour. Be it the ruins of Angkor Wat, the mighty columns of the Temple of Karnak or the serene stillness of a Gothic church, the harmonic proportions, beauty and layout of these masterpieces continue to inspire and amaze.

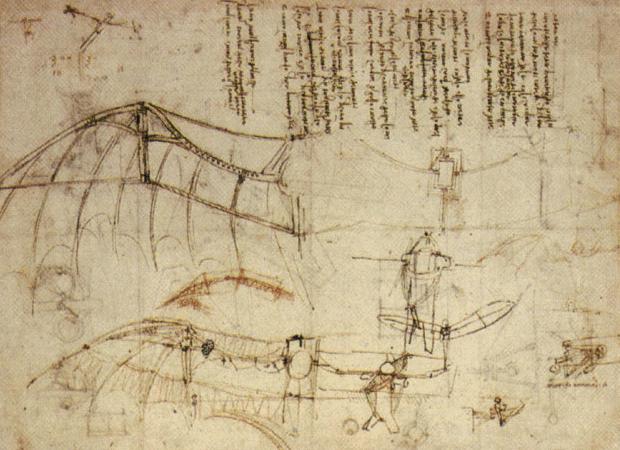

The disciplines that contributed to the mystique of sacred spaces included mathematics, philosophy, art, and religion. Unlike in modern times, it seems that these were not seen as distinctly different sciences, separate and lacking correlation with each other. Instead they were fundamentally interdependent. So we find that in ancient civilisations there was no art that was not religious, no religion that was not philosophical, no philosophy that was not scientific and no science that wasn’t art.

Aside from the obvious art and architectural elements that contributed to the designing of sacred spaces (materials used, colour, symbology) many subtle and invisible elements contributed to the making of sacred spaces. Ancient architects took inspiration from what they saw around them in the natural world as a model of harmonious perfection, a reflection of the Divine. They observed the repeating patterns and natural geometrical principles such as the Golden Ratio, or Golden Mean. Referred to as Phi in mathematics, or expressed as 1:1.618, this ratio is abundantly evident in nature: the flower of an artichoke, chambers of a nautilus sea shell, the positioning of a leaf on a branch, as well as proportions of a human body. The Golden Ratio by itself does not just function as a harmonic proportion but is the primary basis of a philosophical idea that bridges Nature and Life to the temporary world of physical shape.

The use of various geometric proportions, fractals and specific shapes can be seen in the Temple of Karnak, the Pyramids in Giza, the Parthenon in Greece, the Virupaksha temple in Hampi

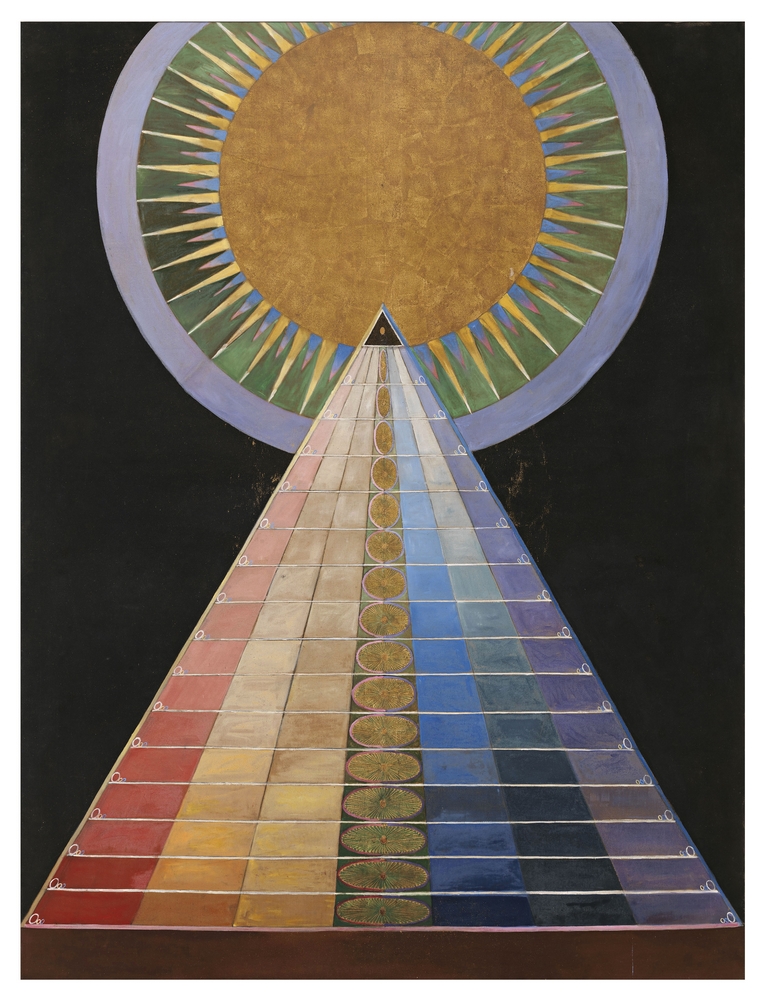

Location and orientation also played an important part in sacred architecture. The concept of “Axis Mundi”, the point of connection between the celestial and the manifest worlds has been referenced universally. This position was considered the point of connection between the earth and the sky where the four cardinal directions intersected. In symbolic terms, this served as the umbilicus, or the cosmic navel, depicting the world’s origins as well as its centre. This centre served as the focal point believed to allow direct access to a higher plane of existence, the abode of the gods. We see examples of this in the choice of location of Machu Pichu (Peru) and The Dome of the Rock (Jerusalem).

Many ancient cultures also designed their structural plans based on the movement of the heavenly bodies. We can observe the example of the Sun Temple in Machu Pichu which was built such that every year, on the winter solstice the sun’s rays would enter through a central window, and fall directly and precisely on a specific ceremonial stone known as the Intihuatana. This showcases their mastery of astronomy together with a deliberate attempt at interacting with the celestial movements. Other examples of similar alignment can be witnessed in Egypt in the Pyramids as well as at Angkor Wat in Cambodia. Scholars such as Eleanor Mannika (University of Pennsylvania) have proposed that even the measurements of Solar and Lunar time cycles were used to determine the positioning of site of Angkor Wat.

Several other structures are built in specific orientation in relation to the cardinal directions. Choirs in many cathedrals are orientated towards the East. The entrance to the sanctum sanctorum of Zoroastrian temples is always from the East or South. Taking the science of such orientation to another level, we find the ancient Indian system of Vaastu Shaastra which prescribes the design and organisation of a space in accordance with laws of nature and the position of the constellations.

Perhaps these elements manifest themselves in all things we deem harmonic and beautiful. By using proportions inspired by nature and through the arrangement and order of other elements such as light, space, and location, architects created a sacred space that facilitated the channelling of “subtle vibrational frequencies” that allowed for the opportunity to connect with the divine. American author and lecturer John Anthony West in his documentary Magical Egypt – An Invisible Science proposes that these vibrations are the means by which the arts are transmitted to us, through our emotional faculties. For example, music which is transmitted through sound waves uses volume, intonation and intensity to create music which we can ‘feel’. Perhaps this is why the great German Poet Goethe called Architecture “frozen music”. Whether it is a great temple or a shopping mall, every edifice communicates its meaning, or lack of meaning, through its vibration. We generally do not associate with it because it is visual vibration communicated through colour, harmony, and proportion. The ancients of various civilisations were evidently aware of this fact.

By using these components of sacred architecture, ancient builders hoped to facilitate the creation of an environment which allowed for and enhanced the ability to connect with the natural, divine laws of life.

In many cases, the design of the sacred complex is itself suggestive of a transformative process expected of the visitor. For instance, the use of parakrams at the ancient Meenakshi Temple (Madurai) requires devotees to go through several steps, symbolic of the stages of spiritual evolution that the worshipper must undergo to realize his true self. Only upon passing the last parakram does the individual reach the holiest part of the temple. In that sense this ritual is a reflection of man’s inner process of learning and purification, leaving behind the temporary self through this long, arduous path, in order to discover his true higher self.

The goal of our lives then is to evolve; to rise and not fall into the traps of the ego of the lower self. Life is therefore a journey in which we each take our own chosen path and travel at our own pace. The purpose of sacred architecture is to help reveal this path, to find, and move towards the Truth. Combining both visible and invisible elements therefore, resulted in harmonic aesthetics and purposeful architectural marvels that served as bridges to help the individual connect the temporary world of form and human experience, to the inspirational world of the eternal laws of life.

Just as each sacred edifice was determined by the laws of life, what if we too could engineer each aspect of our own lives in alignment with them? If we could live in accordance with laws of nature, wouldn’t our bodies too become temples, sacred vehicles, through which to express the best human qualities, devoid of ill thoughts or feelings?

To finish with the words of the modern Sufi Mystic Bawa Muhaiyadeeen:

“Since the soul will live eternally, you must strive to build a beautiful house for it, a house which is not subject to time or to external conditions. For this house, you are the engineer, you are the contractor, and you are the architect; you draw the plan and you set up the system. And when all the planning is completed, you are the one who must construct that house. You must build it alone; no one else can build it for you.”

Bibliography

- Caldwell, Richard. Healing Spaces: Sacred Geometry, Sacred Architecture and the Magic of Intention. http://www.livingdesignconsultants.com/Healing_Spaces_Caldwell_web.pdf

- R.A. Schwaller de Lubicz. The Temple in Man: Sacred Architecture and the Perfect Man. http://fatuma.net/text/R.A.SchwallerdeLubicz-TheTempleinMan-SacredArchitectureandthePerfectMan.pdf

- The Institute for Sacred Architecture. http://sacredarchitecture.org/

- West, John Anthony. Magical Egypt: An Invisible science. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UWnhpn6bY8I/

Image Credits: By David Simonetti | Flickr | CC BY-NC 2.0

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By David Simonetti | Flickr | CC BY-NC 2.0

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

Article References

Bibliography 1. Caldwell, Richard. Healing Spaces: Sacred Geometry, Sacred Architecture and the Magic of Intention. www.livingdesignconsultants.com/Healing_Spaces_Caldwell_web.pdf 2. R.A. Schwaller de Lubicz. The Temple in Man: Sacred Architecture and the Perfect Man. fatuma.net/text/R.A.SchwallerdeLubicz-TheTempleinMan-SacredArchitectureandthePerfectMan.pdf 3. The Institute for Sacred Architecture. sacredarchitecture.org/ 4. West, John Anthony. Magical Egypt: An Invisible science. www.youtube.com/watch?v=UWnhpn6bY8I/

What do you think?