Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms – Art & Sacred Work in the English Middle Ages

Article By Siobhan Cait Farrar

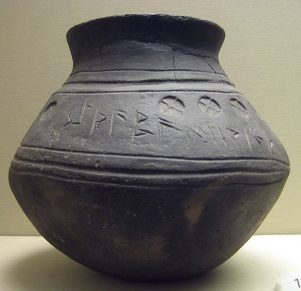

Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War is an exhibition currently running at the British Library and represents a comprehensive exhibit of significant Anglo-Saxon books and precious artefacts. It opens with an extraordinary funerary artefact from the 5th century, the Loveden Hill Urn. Upon the lid of the urn sits an ancient figure, known as the Spong Man, with elbows on knees and holding his head in his hands, as his gaze searches into a mysterious distance, stuck with a strange expression that speaks simply of human struggle, of life and death. The inner world of the potter, still ringing somehow through the eyes of this clay man…

Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War is an exhibition currently running at the British Library and represents a comprehensive exhibit of significant Anglo-Saxon books and precious artefacts. It opens with an extraordinary funerary artefact from the 5th century, the Loveden Hill Urn. Upon the lid of the urn sits an ancient figure, known as the Spong Man, with elbows on knees and holding his head in his hands, as his gaze searches into a mysterious distance, stuck with a strange expression that speaks simply of human struggle, of life and death. The inner world of the potter, still ringing somehow through the eyes of this clay man…

We shortly arrive nearly 200 years later in the 7th century as Christianity is becoming firmly established with the arrival of Saint Augustine and his conversion of the Saxon King, Æthelberht of Kent. During this 7th century, ignited by the first impulse of the early Christian monks, the fertile island rich with the influences of many traditions gives rise to a little known golden age in the north of England – the ‘Northumbrian Renaissance’. This flowering of activity centred around the dual monasteries of Monkwearmouth-Jarrow and a few notable bishops and monks, amongst them the Benedictine monk and historian, the Venerable Bede.

The term Renaissance literally means ‘rebirth’ or ‘reawakening’ and in Celtic Monasticism we see a merging of styles, with a ‘reawakening’ of ideas from Egypt via the influence of the Christian Desert Fathers, Rome and Celtic Britain. According to experts, there are many similarities between the Celtic Monasteries and Coptic churches of the distant Egyptian desert. The Egyptian ancestry of the Celtic church was also acknowledged by contemporaries: in a letter to Charlemagne, the English scholar-monk Alcuin described the Celtic Culdees (meaning Chrisitan communities) as pueri Egyptiaci (Children of Egypt)…

“This house full of delight

Is built on the rock

And indeed the true vine

Transplanted out of Egypt.”

– Antiphonary of the Irish monastery of Bangor

On the intricately patterned carpet pages (full pages) of the great gospel books, notably the Book of Durrow (probably created at Lindisfarne), one glimpses a truly magnificent and profound metaphysical vision. There is a sensation of being transported both upwards and within as your gaze is carried away by the magical drawings. The writer and expert Michelle Brown describes these pages as “portals of prayer” and goes on to say that the “act of copying and transmitting the Gospels was to glimpse the divine… [Just as] St Cuthbert struggled with his demons on the Farne Islands on behalf of all humanity, so the monks who produced the gospel book performed a sustained feat of spiritual and physical endurance”.

The visual timbre of these works transcends culture; it amalgamates, opens up and synthesizes something new arising from the consciousness of the Celtic Middle Ages. The decoration appears at times Islamic, or Tibetan, Egyptian and Roman, then overall becoming gradually distilled into what became the signature Christian style in Europe.

It is somewhat strange to think of England exporting bibles and culture to Rome but during that time, this did indeed happen. Scribes from all over would learn their trade in the monastic colleges of England; notably Canterbury, Winchester and Northumbria.

This exhibition shows the crucial role played by the Anglo-Saxon Britons. With the influence of many traditions they synthesized and defined the sacred art of the incipient new world.

“This precious stone, set in the silver sea, this sceptered isle…This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England”

– Shakespeare (Richard II)

Image Credits: By BabelStone | Wikimedia Commons | CC0 1.0

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

BY BabelStone | Wikimedia Commons | CC0 1.0

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

What do you think?