ART AS A JOURNEY WITHIN – An Interview with Olivia Fraser

Article By The Acropolitan Magazine Editorial team

For centuries art has been a natural means to express one’s inner journey – be it as a community or as an individual search. So has it been for Olivia Fraser, who has used her art to uplift, to produce wonder and beauty, and to find the ‘inner essence’ of things.

For centuries art has been a natural means to express one’s inner journey – be it as a community or as an individual search. So has it been for Olivia Fraser, who has used her art to uplift, to produce wonder and beauty, and to find the ‘inner essence’ of things.

Olivia Fraser moved to India in 1989. Initially she was a travel painter before apprenticing with miniature and Pichwai artists from Jaipur, where she learnt their rich, rigorous and intricate tradition. The influence of Nathdwara Pichwai painting and early 19th century Jodhpuri painting, impelled her to explore its visual language, reaching back to archetypal iconography strongly rooted in India’s artistic and cultural heritage, that could breach borders and was relevant to her twin life between East and West. She has drawn on that enduring tradition, combining it with her deep interest in yoga, to create paintings that could be considered spiritual road maps to reflect an inward journey.

Olivia has exhibited her work all over the world including India, USA, UK, China, Singapore, Italy and Nepal. She has also authored A Journey Within, in which she shares her remarkable artistic journey over the last decade. At the invitation of New Acropolis Culture Circle in December 2021, from her studio in Delhi, Olivia presented some of her paintings in an online talk with our members about the influences that shaped her as a person and as an artist, and induced her internal voyage of self-discovery. These are excerpts from that conversation.

The Acropolitan (TA): Here is Olivia’s first painting titled Dusk. Could you share with us, what is it about Miniature and Pichwai art that impacted you, inspiring you to create this?

The Acropolitan (TA): Here is Olivia’s first painting titled Dusk. Could you share with us, what is it about Miniature and Pichwai art that impacted you, inspiring you to create this?

Olivia Fraser: Back in 1989, I was just a travel painter, looking at the world and painting what I saw in front of me – buildings, people. But then in 2005, I decided to join a gurukul, a studio in Jaipur and then another in Delhi, where I fell in love with the rigor of miniature painting just by viewing them in the National Museum. Observing the jewel-like colors, the burnished surfaces, the stylized landscapes, the particular way of patterning, I decided I was going to learn how to do this. And I was going to treat this like the process of learning a language, understanding my presence here as a foreigner, but trying to get in on the inside; not just painting on the outside. I also fell in love with Pichwai paintings: the large-scale temple backdrops used in the Nathdwara temple which houses the icon of Shrinathji. I particularly loved their strong sense of structure and also the sacred geometries associated with Shrinathji.

I also like the idea of how numbers are so important. For example, the proportion of how tall a tree is, in comparison to how tall a cow is. Even the features of Shrinathji, the proportion of how you actually painted them was related to the proportions of the actual original deity housed in Nathdwara. All proportions are intensely sought out, as is color and patterning. There is a refining down to an essence, and that is what excited me. And having painted the world outside, I felt this was about extracting the noise and getting down to something more central.

I like the flatness and the different attitude to perspective used in this traditional form of painting where distance is less important than sacrality. For this painting I was thinking about coming into a sacred space- as emphasized by the cows walking into the recessed circle within the square Yantra space. Line leads into form and each cow is “equal”: there is no hierarchy, and, as it’s about sacrality, no distance. So, that is the background to this painting.

TA: There is another beautiful painting which also may have been inspired by Pichwai art – Lotus Eyes. Could you share your perspective?

TA: There is another beautiful painting which also may have been inspired by Pichwai art – Lotus Eyes. Could you share your perspective?

Olivia: So, I have done many eyes over the years. The idea originally came when I went to Nathdwara and I saw the deity there and did darshan. You look at the deity and the deity looks back. The concept of darshan is like having an exchange. I love this idea because coming from the west, I didn’t have this understanding. In a way, this reflects the whole business of what one does with art – an exchange of visions. An art work becomes an art work only when someone else is looking at it. So, the title Lotus Eyes is also darshan.

In Tamil Nadu, South India, when watching artists that are still making Chola bronzes today, we see that the last thing that they put onto their icon are the eyes. When I travelled around in Rajasthan and saw the mobile Phad paintings that artists would paint of the local deities (Pabuji ka Phad), again the last thing that the artist would do, would be to paint the eyes in. Suddenly that would transform the image, to become a mobile temple.

I suppose another idea behind all my ‘eyes’ is connected with my practice of yoga. My yoga teacher has taught me a particularly visual form of meditation; it is just eyes that instantly come to me, or rather, one eye. Hence, I realize how my art reflects these personal influences. What my yoga teacher

taught me, is similar in a way to what I grasped within the process of learning traditional Indian painting, Miniature painting, and Pichwai painting. It is essentially about using the outside, literally, the ground, the sap from the tree, which you take and use in your painting. Then you could paint on top of it. Or you can use kadia – the chalk from the cliffs around Jaipur which becomes this lovely natural off-white, slightly powdery, wonderfully textured, gentle white. It’s not stark, but a kind of beautiful white which I use as my background… It is the background of this painting. I just adore that gentle white.

Using almost all the things I could see – the macrocosm of the world around, has become my inspiration, to use in my studio and likewise in my yoga. Creating visualizations using a sacred landscape, flowers, chakras, snakes, or any motifs that one may harness in one’s yogic meditation. I feel that has been very special and has totally influenced what I paint.

TA: You say that a lot of your paintings are like spiritual roadmaps that reflect the journey within. The next painting called The Scent of the Lotus seems to start from a point of stillness that transforms to movement. How are you able to take something as subtle as meditation and express it visually?

TA: You say that a lot of your paintings are like spiritual roadmaps that reflect the journey within. The next painting called The Scent of the Lotus seems to start from a point of stillness that transforms to movement. How are you able to take something as subtle as meditation and express it visually?

Olivia: Well, I think my yoga teacher has provided the visual stimulus by suggestion. But I have also read this wonderful book called Gheranda Samhita. It is a yogic treatise written around late 17th century, and it has some of the most wonderful descriptions of visualizations: of bringing in the landscape and harnessing all the senses. I do yoga outside in the garden with lots of trees, and you can hear the birds, you can see the leaves, and what I am trying to say perhaps is that things don’t fully stop. There isn’t a total stillness. You try to focus when you are meditating, yet there is this constant movement; the movement basically of the breath. There is a stillness that you aim for, but there is also contrasting movement and the effort to get those two together.

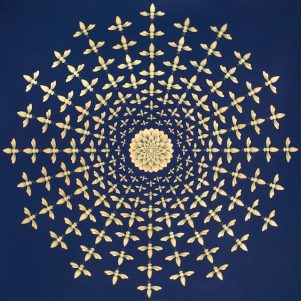

In a way, the Miniature art form is also very still, and that is one of the things that I love about it, but there is also a kind of movement in the patterning. So, I was trying to get that effect, particularly with this painting. I was thinking also about the sense of smell. I have been thinking about all the different senses that artists over the years have tried to depict. Rothko tried to show sound, and Kandinsky too. Here I was thinking about both sound and smell. Also, about bees. I had always been terrified of bees because I was stung quite a bit as a child and then I remember first doing bhramari – one of the yogic practices which I learnt relatively recently, where you make the sound of a bee… that inspired this and various other paintings. There is also a lot of poetry about bees. Krishna is often described as a bee, going from flower to flower. And the lotuses being his gopis. Or the other way around; I love the whole way that things cross over, so the gopis are sometimes thought of as desirous, surrounded by a swirl of bees, or with gorgeous bee hives, and from this emerged the idea for this painting.

One of the reasons that I paint so much with blue (this is indigo, another handmade color, not a stone pigment, but a plant pigment), is obviously a reflection of my thinking of Krishna. What I am doing here is emulating in a way, the traditional sacred art. With the cows in the earlier piece I was using the two different colors of Krishna: as a child, where he is painted in a very dark, blue-black color, and then as a young man, where he is much lighter. When you see depictions of Krishna as a youth, a goat herder, he is a much softer, lighter blue. So, that was why the cows were these two different blues, echoing Krishna and implying the sacred. My usage of gold, which is precious, is again associated with the sacred.

TA: There is meaning behind everything you do, whether it’s the pattern, the rhythm, the shape or the colors. You use gold leaf very often, for example in the painting called The Golden Lotus.

Olivia: I think I looked at the sacred dimensions of an image of Srinathji in creating this. I was using that whole idea of the lotus leaf that the Golden Lotus is perched on, as a halo of sorts. Many maharajas have a green halo so I used this idea, and of course the circle and the square again, implying heaven and earth.

The golden lotus in particular has been something that I have also loved as a visualization. A rather simple but iconographic image.

TA: In this painting the lotus petals look like a kind of a mudra and I remember you shared a lovely story with us about learning Bharatnatyam. Could you share that with our members?

Olivia: Yes. There’s a treatise on Indian painting I think, the Vishnu Purana, and in it there’s a discussion between two people, Vajra and Markandeya. They’re talking about how to make a work of art. Vajra asks, “Speak to me about the making of the images of deities, so that the deity may remain always close by and may have an appearance in accordance with the shastras.” Markandeya responds, “First of all you must learn how to dance.” And Vajra says, “And once I’ve learned how to dance, can you then tell me how to make the perfect image?” Markandeya replies, “No. Then…you must learn about music.” So Vajra says, “Well, then, once I’ve learned music will you then divulge the secrets of how to create an artwork?” And Markandeya says, “No, once you’ve learned music, then you need to learn how to sing.” So, I love this idea here, of combining art forms in a way that I think India does, while the west compartmentalizes things.

I started learning miniature painting at the same time as I began learning Bharatnatyam. The dance form is all about movement with imagery created with your hands, your body and your position within a sacred space. It reflected perfectly the strength and confidence of the imagery that I was so attracted to in the painting tradition.

I could never paint trees back in the past. I just looked at trees and I was baffled by them! When I came to India and asked my guru, “How can I learn to draw a banana tree? Shall I go outside and do it?” He said, “No, it’s got to be something you look for within. There’s only one way of painting a banana leaf.” I loved that idea; of actually just calming down, to reflect, look inside and reach for the absolute essence! And within that essence, there will be something that’s almost dance-like. I was able to sense everything as always full of flow. It’s about following the breath, which is the same as it is with dance; it’s the same with singing, and it is the same combination of all these things when you’re trying to create an image.

TA: That’s beautiful! Thank you. You seem to consider western art to be more external, whereas Indian art to be more internal. Can you speak to us a little about that?

Olivia: This piece is called The Moon. This is a fairly recent one…started just before the pandemic, and continued through it. I think it has a lot of influence from the west but you can also see the sky imagery and the cloud motif that I’ve taken from what you see in lots of miniature paintings.

I am interested in looking at the backgrounds in paintings, at the landscape, at nature, then taking that and bringing it into the foreground, because I am the person who’s walking through the landscape. One of the things I love about yoga is thinking about the landscape being within. I grew up in the west, studied languages and then I went to art school and perhaps that’s why I’ve been thinking of and treating my art as a language.

I’d say my journey has been one from having painted from life… having started off with life drawings, life paintings, sketches of people and architecture to painting a landscape within. So, from having looked at and experienced things from the outside, to then bringing the outside into my studio, looking inwards and being guided to do this through art, dance and yoga. I would say that my life in India has brought about an internal journey, which has led to an internal vision. And that’s where I am now.

All images of artworks included in this interview have been reproduced with permission from Olivia Fraser.

Image Credits: Image Courtesy Olivia Fraser

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

Images Courtesy Olivia Fraser

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

Article References

theacropolitan.in/

What do you think?