Giordano Bruno: Some Life Lessons

Article By Ambuj Dixit

“And how many years can some people exist

“And how many years can some people exist

Before they’re allowed to be free?

Yes, and how many times can a man turn his head

And pretend that he just doesn’t see?

How many times must a man look up

Before he can see the sky?”

These lines from Bob Dylan’s song – Blowing in the Wind – flashed in my head as I put down another book written on Giordano Bruno, arguably one of the greatest philosophers from the 16th Century. The lines of the song and Giordano Bruno’s quest seem to echo each other – to urge humanity to look beyond the dark sheaths of ignorance, the petty disputes, divisions and one-upmanship, and to explore the true identity of what it means to be human, which is much more than the mode of survival that has become the focus of our ‘living’, today.

Between the Middle Ages in Europe when it was engulfed in darkness, and today where we admire the marvels of human creation, connectedness, technological advancement, and medical progress, have we really become smarter, happier, more loving and caring? Why does it feel that the last few hundred years of progress have largely been about attempts to master the everchanging outside, without ever addressing the real core of the problem? Have we even spent enough time to understand what the core is? Have we made progress towards finding out what our life is about and who we really are?

Allow me to give you a bit of background on Giordano Bruno, that could lend a fresh perspective to this investigation.

Giordano Bruno was an Italian philosopher, astronomer, and mathematician whose theories presented a vision of the world which emphasized the infinite. He was a prominent figure during the Renaissance, when Europe was witnessing the resuscitation of the idea of unity – the link between the one and the many.

Born in 1548 in Naples, Italy, he lived a life of wonder, investigation and reflection about the universe and man’s connection to, and role within it. At seventeen, he entered the Dominican monastery of San Domenico Maggiore, in Naples. He became a priest at the age of twenty-four and received the equivalent of a doctorate in theology three years later. He was apparently a bright student and also, now and then, an exasperated one, who did not agree with some of the principles of the teachings he received – for example, that of geocentricity that postulates earth as the centre of the universe. Around the age of twenty-seven, Bruno heard that he was being investigated by the Inquisition for heresy (1).

He left for Switzerland immediately and stayed on the run escaping the watchful eyes of the Church for the next fifteen years. He travelled extensively — Geneva, Toulouse, Lyon, Paris, London, Oxford, Wittenberg, Prague, Helmstedt, Frankfurt, Zurich, Padua, Venice—never staying more than two or three years in any city. During his lifetime, he produced some thirty works, including treatises, pamphlets, dialogues, poems, and even a play (1).

Some of the fundamental ideas on which his teachings were based included heliocentrism, the notion that sun is the centre of our solar system; an infinite cosmos, consisting of many such solar systems; everything that exists is made up of identical particles – “seeds”, in his terminology, and God resides in all these seeds, and that this unifies the world (1). Needless to say, all these ideas were in direct opposition with those of the Church, at that time.

In 1592, during a secret visit to Venice, Italy, he was betrayed by one of his students and was thus captured by the Inquisition. Tried for heresy by the Church, he was asked to recant if he wanted to save his life, but he adamantly refused to do so. He was declared an ‘impenitent, pertinacious, and obstinate heretic,’ and condemned to die. In 1600, he was burnt at the stake.

The idea of sharing the story of Giordano Bruno is not to learn the various theories he proposed, but to investigate if through his heroic life, we can find some answers to what is perhaps the most essential question that humanity has been facing – Who am I?

Humanity seems to be lost in its attachment with the everchanging form and the multiplicity that is prevalent all around us. The lack of discernment between the invisible, essential and eternal, from the illusory, material and temporary, results in an inordinate identification with the mortal body – leading to insecurity and frustration with regard to one’s own limitedness. With the absence of a relevant perspective on what role the material and the visible plays in the realm of human purpose, the various forms that nature has served us with, seems to be confusing and overwhelming. Is there a way to understand the essence and connect with it again?

Annie Besant, in her book on Giordano Bruno, states, “Form is the manifestation of the unity”. She adds,“Unity manifests itself in three hypostases. The 1st is Thought: The act of divine thought, according to Giordano Bruno, is the substance of things, the root of all particular beings….

The 2nd and 3rd hypostases of Universal Being are Spirit and Matter, where Spirit is the formative element, and the matter is the receptive element that takes shape as per the spirit.” (2)

If we extend this insight to the mortal aspect of the human being that we identify with – the body – we will see that Bruno is guiding us to assign the body its proper place. “The body is in the soul, the soul is in the thought and the Thought is either divine or is in the divine. .” (2)

“The soul of man is the only God there is. This principle in man moves and governs the body, is superior to the body, and cannot be constrained by it. It is Spirit, the real self, in which, from which and through which are formed the different bodies, which have to pass through different kinds of existences, names and destinies.” (1)

If all the plurality and multiplicity we see around us are different kinds of existences, names and destinies of the same divine that is in all of us, maybe finally, we can better understand Bob Dylan’s question – How many years can some people exist, before they’re allowed to be free? Maybe, he is referring to the freedom from our illusions, to be able to see the underlying connection in everything we have around us; freedom to see the forest, instead of the hundreds of trees it is made of. Both Dylan and Bruno seem to be suggesting that we have caged ourselves in the illusion of separation, emerging out of attachment to the external.

This might look like advice beyond our capabilities, but if we look past our doubts, life will provide experiences that will strengthen this conviction that there is more to ourselves, and to life, beyond what we see. With this recognition, we may also come to realize the control we actually have – not over circumstances and other people, but definitely over our own approach, and our responses.

We can start with the small acts – like when angry and vulnerable to our impulsive self, try to be objective and remember that I am not my impulse. If I love food, then instead of giving in to the impulsive tendencies of the tongue, know that it is the body that is craving for food and its interest would be better served not with surfeit but with measured quantities. Rather than becoming irritated in a traffic jam, use it as an opportunity for productive ‘me time’.

Life presents us with opportunities to grow every day, to learn the difference between the temporary and the eternal and to continue to improve our ability to make wiser choices, by choosing spirit over matter.

And what if we took some steps, but failed? What is the worst that may happen? We might fall back into our ingrained habits, impulses, and tendencies. But what if we experience something different? What if one small step leads to another small step, and then another, and one day a change in perspective occurs that opens a whole new world altogether?

Bruno, like many philosophers, had great faith in human potential and man’s ability to aspire to goodness. He writes, “Enough that all should run; enough that each should do that which is possible for him; since the heroic mind is content rather to fall or to fail worthily and in a high cause wherein the dignity of his spirit is shown forth, than to achieve perfection in things less noble or even base.”

He adds, ‘profound magic is to know how to unite contraries, having found the point of union’. When we learn to go beyond the multiplicity, we will realize that what unites us is actually far more important than what divides us. We learn how to simplify life because we understand the laws of the Universe that govern all life forms, govern us too. We let go of constant overthinking by introducing ourselves to the innate intelligence that guides all living forms. We connect to the magic called life.

Perhaps Giordano Bruno’s life can inspire us to explore the magic of uniting the contraries enabling us to clearly see the unifying sky, about which Bob Dylan so passionately sang to us all!

Happy adventure!

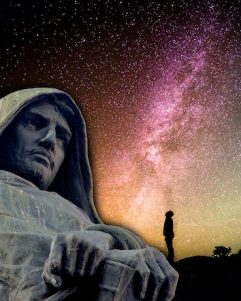

Image Credits: by Maurizio Martella / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-4.0

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By Maurizio Martella / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-4.0

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

Article References

Bibliography 1.www.newyorker.com/magazine/2008/08/25/the-forbidden-world 2.Giordano Bruno by Annie Besant, Publisher: The Theosophist Office

What do you think?