Gitanjali by Tagore: An Investigation

Article By Prof. Ananda Lal

On 29th March 2021, The New Acropolis Culture Circle conducted an online session on Rabindranath Tagore’s Nobel Prize-winning work Gitanjali, with Prof. Ananda Lal.

On 29th March 2021, The New Acropolis Culture Circle conducted an online session on Rabindranath Tagore’s Nobel Prize-winning work Gitanjali, with Prof. Ananda Lal.

An authority on Tagore, he retired as Professor of English, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, and directs Writers Workshop, the oldest continuing publisher of Indian poetry in English.

The professor’s doctoral thesis had become the first English book exclusively on Tagorean drama, titled Rabindranath Tagore: Three Plays, in 1987. He sang, recited and shared his investigation of Tagore’s Gitanjali, highlighting that Tagore propounded a practical faith, his manifesto of ethical action coming from the strong conviction in a universal God while suggesting that only through our actions could we own responsibility towards ourselves and others.

Below is a synthesis of the conversation.

One often notices within our society that we hero-worship our great iconic heroes in cultural, artistic and intellectual spaces but we don’t actually read their works or practise the ideals they espoused. Investigating Gitanjali can catalyse a deep personal transformation. This book reflects the immense wisdom and true renaissance quality of Tagore’s genius and multifaceted personality.

The original Gitanjali was written and published in 1910, consisting of 157 poems and songs in the Bengali text. The significant context worth putting forth is that between 1902 and 1907 Tagore suffered four major bereavements in his immediate family: his wife passed away at a relatively young age in 1902; his 12-year-old daughter in 1903; 1905 saw the death of his father whom he was immensely close to; and in 1907 his youngest son died. These traumatic events appear to have been the trigger for the immense seeking of the truth and the focus on deep spirituality in Gitanjali. Furthermore, since his youngest years, Tagore had been a member of Brahmo Samaj, one of the reformist movements within Hinduism in the 19th century. He later developed a strong attraction to Buddhism. As a voracious reader, he had also read a lot on Christianity. All this influenced his works.

In the two years he took to write the poems he also composed music to the majority of them. The literal meaning of the word gitanjali means “song offerings”, of a devotional nature. And while listening to them, we realize how the beauty of the music transcends that of poetry. Tagore was deeply inspired not just by Vedic hymns, classical songs and kirtans in the Hindu tradition, but his songs (Rabindra-sangeet) also owe melodies to Baul folksongs from countryside Bengal. A syncretic denomination of minstrels, Bauls sing travelling from village to village; they draw their faith from Sufism and Vaishnavism and believe in their conviction of a direct hotline from one’s heart to God. Tagore even borrowed from devotional songs as far apart as Sikh bhajans and Carnatic songs.

In his English Gitanjali, however, he took only 53 from his original 157 lyrics and added another 50 from his other publications. So, the English Gitanjali of 103 songs is not a close equivalent to the original Bengali, and is also a creative translation in prose poetry. Tagore shared these transcreations in 1912 as a manuscript with his friend William Rothenstein in London. Rothenstein’s circle was so overwhelmed by the poems in this manuscript that they decided to publish it that very year in 1912 and, surprisingly in 1913, the Nobel Prize committee awarded him the Prize for Literature, the first ever to go to a non-European. Gitanjali accorded Tagore an iconic status across the world. His poetry evoked, universally, a deep connection with the beauty of the ideal and the invisible divine, especially at a time when the West had moved away from spirituality in their quest for modernity.

Tagore once rhetorically asked, “Can you squeeze me behind any one religious boundary?” reflecting his belief in a universal idea of God without conforming to an esoteric religious identity. It is this extremely secular idea of faith that Tagore lived by. He hardly ever mentioned any “God” by name, but rather as a supreme spiritual force that compels us to act rightly. His need for a practical faith and a deeply ethical life is reflected in Verse 4:

“Life of my life, I shall ever try to keep my body pure, knowing that thy living touch is upon all my limbs.

I shall ever try to keep all untruths out from my thoughts, knowing that thou art that truth which has kindled the light of reason in my mind.

I shall ever try to drive all evils away from my heart and keep my love in flower, knowing that thou hast thy seat in the inmost shrine of my heart.

And it shall be my endeavour to reveal thee in my actions, knowing it is thy power gives me strength to act.”

Verse 11 in his English Gitanjali is pertinent to our times:

“Leave this chanting and singing and telling of beads! Whom dost thou worship in this lonely dark corner of a temple with doors all shut? Open thine eyes and see thy God is not before thee!

He is there where the tiller is tilling the hard ground and where the path-maker is breaking stones. He is with them in sun and in shower, and his garment is covered with dust.

Put off thy holy mantle and even like him come down on the dusty soil! …

Come out of thy meditations and leave aside thy flowers and incense! What harm is there if thy clothes become tattered and stained? Meet him and stand by him in toil and in sweat of thy brow.”

I would term this as deeply empathetic, advocating a sense of worship that celebrates humanity all around us and dismisses the entire idea of being able to worship only inside a particular building. One worships with the people who are labouring around us, without any inhibitions, without needing any designated location.

Song 4 in Bengali Gitanjali opens with this couplet (in my translation):

“It is not my prayer that you protect me from danger!

May I remain fearless at times of danger!”

The song celebrates this approach of fearlessness, not pleading to the supreme power as one conventionally does in prayer, but focusing on the virtue of fearlessness, as Gandhiji would say, to strive to be the change that one wants to see.

Verse 29 of the English version tells us about the dangers of self-absorption:

“He whom I enclose with my name is weeping in this dungeon. I am ever busy building this wall all around; and as this wall goes up into the sky day by day I lose sight of my true being in its dark shadow.

I take pride in this great wall, and I plaster it with dust and sand lest a least hole should be left in this name; and for all the care I take I lose sight of my true being.”

All philosophies have always propounded, “Drop the desire for fame, drop the ego!” The wall-building is the metaphor for building the ego, the desire for fame.

Verse 31 is in the form of a dialogue. One person says:

“Prisoner, tell me, who was it that bound you?”

“It was my master”, said the prisoner. “I thought I could outdo everybody in the world in wealth and power, and I amassed in my own treasure-house, the money due to my king.

(Tagore used the terms ‘King’ and ‘Master’ for the Supreme force) When sleep overcame me, I lay upon the bed that was for my lord, and on waking up I found I was a prisoner in my own treasure house.”

“Prisoner, tell me who was it that wrought this unbreakable chain?”

“It was I,” said the prisoner, “who forged this chain very carefully. I thought my invincible power would hold the world captive leaving me in a freedom undisturbed. Thus night and day I worked at the chain with huge fires and cruel hard strokes. When at last the work was done and the links were complete and unbreakable, I found that it held me in its grip.”

Tagore always criticized power and materialism for its own sake. The more one accumulates treasures, and the more one amasses all the power in the world, one is actually chained.

The poem 106 in Bengali gives us Tagore’s idea of India as a great land that integrated in its sacredness so many cultures and religions. Here is my translation:

No one knows whose call made streams of so many populations

Come from where on turbulent currents, lose themselves in an ocean.

Here Aryans, here non-Aryans, here Dravidians, Chinese—

Sakas, Huns, Pathans, Mughals dissolved in one body.

The doors open to the West today,

All bring gifts from there,

Give and take, meet and merge, no one turns to leave—

On this seashore of India’s great humanity.

Come O Aryans, come non-Aryans, Hindus, Muslims.

Come today, come you English, come, come Christians.

Come Brahmins, cleanse the mind, hold the hands of everyone.

Come O fallen, may the load of all insult be undone.

Come, come to Ma’s consecration quick,

The auspicious pitcher hasn’t yet filled

With pilgrim-water sanctified by the touch of everybody—

Today on the seashore of India’s great humanity.

In 1911, Tagore wrote what eventually became India’s National Anthem, where he incorporated the above idea, but addressed to God. Most Indians don’t know the second stanza, which goes something like this (in my translation, trying to preserve the original rhyming pattern):

Hearing your call always proclaimed – your noble maxim,

Hindu, Buddhist, Sikh, Jain, Parsi, Christian, Muslim,

East and West arrived

To your throne’s side

A necklace of love to create.

Victory to the Mover of people’s unity, God of India’s fate!

Tagore also celebrated the idea of a global citizen or, more philosophically speaking, the idea of fraternity beyond any distinction of nationality, religion, culture and race. He propagated internationalism, or humanism taken to the global level. Thus, Verse 63 in the English Gitanjali:

“Thou hast made me known to friends whom I knew not. Thou hast given me seats in homes not my own. Thou hast brought the distant near and made a brother of the stranger. …

When one knows thee, then alien there is none, then no door is shut. Oh, grant me my prayer that I may never lose the bliss of the touch of the one in the play of the many.”

Gitanjali contains so many dimensions. Verse 52, strikingly different, is an ode to the strength or Shakti that the feminine force needs to manifest:

“The morning bird twitters and asks, ‘Woman, what hast thou got?’ No, it is no flower, nor spices, nor vase of perfumed water—it is thy dreadful sword.

I sit and muse in wonder, what gift is this of thine. I can find no place where to hide it. I am ashamed to wear it, frail as I am, and it hurts me when I press it to my bosom. Yet shall I bear in my heart this honour of the burden of pain, this gift of thine.

… Thy sword is with me to cut asunder my bonds, and there shall be no fear left for me in the world.

From now I leave off all petty decorations. Lord of my heart, no more shall there be for me waiting and weeping in corners, no more coyness and sweetness of demeanour. Thou hast given me thy sword for adornment. No more doll’s decorations for me!”

His call to women to take up the sword does not imply a fight in the literal sense – the message being, not to be meek or submissive at all, which is deeply inspiring considering the stereotype of women more than a century ago.

Tagore was one of the earliest pioneers of the green movement in India. Deeply engaged with nature, with the environment, he celebrated the advent of different seasons with festivals for the students in Santiniketan. Spring was for him a celebration of the rejuvenation of the year, with colour, life, love, and renewal. He always played on the paradoxical relationship between Arupa, the formless, which in India is just one of the names of the Supreme, and that of the multitude of forms, or rupa. The moment we enclose that Supreme power in just one form, it’s necessarily incomplete. Tagore celebrated the paradox of how, spiritually speaking, Arupa is omnipresent, yet we physically see only the multitudes of rupa all around us. But through nature’s beauty, we can actually see the immanence of Godhead right in front of us.

Tagore’s poetry expressed deep gratitude for the opportunity to be born as a human being, the absolute celebration of being invited to experience human existence, so one must make the most of it. In one of his pieces on the beauty of birth, Verse 61, he serenely asks from where the smile on a sleeping baby’s face comes, while the English Gitanjali ends with several poems about death. So, from birth to death, Tagore is ready to embrace all, because both are part of life. Death is not sorrow, but a continuation of Life. I end with his Verse 95:

“I was not aware of the moment when I first crossed the threshold of this life.

What was the power that made me open out into this vast mystery like a bud in the forest at midnight!

When in the morning I looked upon the light I felt in a moment that I was no stranger in this world, that the inscrutable without name and form had taken me in its arms in the form of my own mother.

Even so, in death the same unknown will appear as ever known to me. And because I love this life, I know I shall love death as well.

The child cries out when from the right breast the mother takes it away, in the very next moment to find in the left one its consolation.”

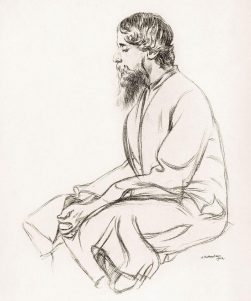

Image Credits: By William Rothenstein / Wikimedia Commons / PD US

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By William Rothenstein / Wikimedia Commons / PD US

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

What do you think?