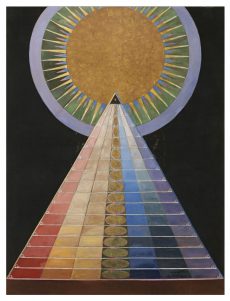

Hilma Af Klint: Painting the Unseen

Article By Siobhan Farrar

Earlier this year the Serpentine Gallery held an exhibition described by the Telegraph as “a sense of unfathomable mystery”.

Earlier this year the Serpentine Gallery held an exhibition described by the Telegraph as “a sense of unfathomable mystery”.

Hilma Af Klint, a Swedish born female painter who began producing work in the early 1900s, is beginning to be recognised as the first artist ever to have produced a piece of ‘abstract art’. Prior to her discovery, abstract art was considered to have begun famously with Wassily Kandinsky’s watercolours in 1910.

“The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brush stroke.”

This is the description Hilma gave in one of her meticulously catalogued sketchbooks describing her series ‘Paintings for the Temple’ – a collection of 193 pieces, some of which are 3 metres in height.

The curator who put on her show at the Moderna Museet in 2013 explains,

“The overall idea is to convey the knowledge of how all is one, beyond the visible dualistic world. The temple to which the title refers does not necessarily relate to an actual building but can rather be seen as a metaphor for spiritual evolution.”

Hilma Af Klint was a Theosophist and, later, an Anthroposophist. At that time, the Western world was seeing discoveries proving the existence of things beyond the tangible, such as Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen’s discovery of X-rays in 1895 and Hertz’s discovery of electromagnetic waves shortly before. The worlds of both science and art were inspired by the notion of observing new forces and hidden realities in nature.

Unusually for a professional painter, Hilma never intended to show any of these ‘abstract works’ during her lifetime. It was her request that the work remain unseen until at least 20 years after her death, which came in 1944.

As a classically trained painter with a formal education at art school, during her working life Hilma was known for producing botanical drawings and realistic landscape paintings.

A paradoxical relationship may be said to exist between Hilma’s professional botanical drawings and her hidden, abstract paintings. In her professional drawings Hilma applies a scientific approach, neither adding nor subtracting detail to the naturalist landscapes and botanical drawings that she produces. In her abstract, otherworldly creations, we see a reflection of this diligence and consistency in the symbols that she uses to repeatedly depict the themes of unity, of duality and of male and female forces.

It is hard perhaps for us today to grasp the enormity of Hilma’s story. Producing the first piece of ‘abstract art’ as a female painter at the turn of the century is a remarkable feat. She painted in a way that had never been done before and set marks upon canvas for which there was no precedent.

It has taken much longer than 20 years for Hilma’s work to be seen and recognised as important within a wider artistic canon. However, if Hilma’s intuition was correct and the world is now more open to a universal principle of unity and a deeper understanding of duality in nature, then perhaps we are approaching a time of inspiration in humanity for further discoveries of the hidden forces in nature.

Image Credits: By www.kunstkritikk.no/kritikk/hilma-af-klint-diagram-artist | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By www.kunstkritikk.no/kritikk/hilma-af-klint-diagram-artist | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

What do you think?