Philosophical Principles of Sanskrit

Article By Bhavna Roy

“In the beginning was the word, and the word was God.” – John 1:1

“Om is everything; the past, the present, and the future is an expression of Om.” – Mandukya Upanishad

As if echoing these ancient scriptures, quantum physicists state that creation began with the Big Bang – a first pulse of vibration; vibration is sound. The beginning of creation is therefore conceived as a primordial word. As creatures evolved, creation itself developed protocols to interact within the created world. When exactly did humans develop a flair for ordering, organising and harmonising sound within layers of the complexity and sophistication of language? I guess we will never know!

Languages are born in the crucible of a core culture, which shapes its nuances and its very nature, in a subtle though seminal fashion. Classical Sanskrit emerged from the minds of a people whose life was defined by a philosophical exploration of the myriad components of life. Blessed by nature, these prescient people observed the mathematical precision and harmony that exists in the world of form: the plants and animals, the sun, the moon and the stars – the very universe that they believed they were an intrinsic, if infinitesimal, component of. Sanskrit, known as devabhasha, the language of the Gods, as if pre-existing, is said to have been re-discovered as a process of this philosophical exploration, and demonstrated the precision and wisdom woven into its very structure. The language can therefore be understood at a deeper, more philosophical level; for it was a language which did not aim to spread or conquer, but to explore and decode life. Communication was a valid, though minor aspect of its overall purpose.

The rules of Sanskrit, orally preserved since times immemorial, got codified around 6th and 5th century BCE by Panini, whose Ashtadhyayi is the foundational text of Sanskrit grammar as we know it today. Intriguingly, its grammar nudges one toward introspection, the world within, something unmet by many modern languages.

The Vaidika people discovered and adhered to some foundational concepts in early mathematics. This mathematical understanding is reflected in the rules and governing principles of Sanskrit, which are logical and therefore inflexible, requiring no exceptions. It did, however, allow for flexibility within the rule, for example: 1+3+5+2 = 3+1+2+5 = 11. In keeping with this mathematical truism, unlike in English, the position of the subject, object, verb, preposition, etc do not change the meaning of a sentence! This perhaps suggests the inherent importance of the conveyed essence of a sentence, rather than a preoccupation with the form (the sentence structure) in which the essence is conveyed – for the world of form, the rupa, is conceived of as an every-changing realm of illusions through which an investigative philosopher must traverse to grasp the essential, the principle, the eternal.

Furthermore, the Sanskrit alphabet – varna – has two types of syllables:

- svara, the 16 vowels, considered sampurna or complete sounds

- vyanjana, the 33 consonants which are a-sampurna, or not-complete sounds.

The consonants therefore need to ‘mate’ with the vowels in order to emerge as sound. The emergent consonants are systematically categorised after analysing the anatomical and vibrational basis of the sound: gutturals, linguals, palatals, dentals, labials, and nasal. The nasal sounds are further sub-divided into the Soorya (Sun) section, which is the right side of the nasal stream, and the Chandra (Moon) section, which is the left side of the nasal stream.

There is an intriguing philosophical twist to the word that can be used for the object, in a sentence. The object is the result of an interrogative pronoun: WHO, WHAT, WHICH, WHOSE, WHOM. For instance, when a devotee, deep in bhakti, professes his love for the divine, he might say, “I love Raam.” Note each component of the statement:

English Sanskrit

Verb to love snih – conjugated with ‘I’ as snihyaami

Subject I aham

Object Raam raamam, raamaay, raame – depending on intended meaning

If there is an expectation of return in the act of loving, for instance, then we may use the dvitiya (accusative) form of the object:

aham snihyaami raamam

raamam implies that the speaker expects a return for his act of loving, perhaps blessings.

If, on the other hand, there is no expectation of return in the act of loving, we may use the chaturthi (dative) form of the object. Introspective wisdom was built into the very grammar of the language!

aham snihyaami raamaay

raamaay implies that the speaker chooses to love Lord Raam and simply rejoice in that bliss, without any expectation.

Finally, the object can also be expressed in the locative case (which corresponds to the English prepositions IN, ON, AT, BY):

aham snihyaami raame

By using raame the speaker declares with a flourish: my love locates me within Raam.

Incidentally, the root word for love, snih, is in practice only combined with the locative form of the object: aham snihyaami tvayi, meaning I am located in you. Not aham snihyaami tvaam, which would be the accusative and therefore a ‘separating’ form of the object. These philosophers recognised the very nature of love as unifying, locating oneself in the other, and not separating; and they took care to weave this attitude into the grammar associated with the language. So much for the bland, “I love you!”

While all modern languages have singular and plural forms, in Sanskrit each noun also has a dual form: the one, the two, and the many. The ancients had a clear conception of the divine unity, The One which expresses itself into duality, bringing forth the plurality of creation. This principle was embedded into the language itself.

A ‘mood’ is suggestive of the manner in which a verb is used. In the English language, there is no imperative or benedictive mood in the first person singular that can be used as an ending of a sentence; meaning that the speaker cannot permit or request himself to act, except when part of a larger group. For instance, we cannot say, “Love I”. However, both the imperative mood (lot) and the benedictive mood (asheerling) in Sanskrit, imagine grounds for the existence of the first person singular as an ending! I can permit myself to love me, tutor me, lead me, berate me…! This suggests a dual sense of self; perhaps a higher (the eternal) and lower (the personality which is conditioned by ever-changing circumstances, and through which one interacts with the manifest world). So I, the lower self, can aspire to earn the blessings of I, the higher self! No doubt, English too gives space to the philosophical idea, “I bless me.” However, in doing so, the grammar of English treats ‘me’ as an object to I, rather than as the subject!

Be it in the seemingly simple aspect of the locative case being necessary for the root verb “to love”, or in the seemingly complex ocean that is the self-confronting tense of lot and asheerling, Sanskrit has the capacity to shift the axis that balances the experience of life. We can choose to check in at the kindergarten level and learn to speak a language. Or, if suitably adventurous in a philosophical sense, we can unleash the very potential of what it means to be human, through a language that gently shepherds us into discovering principles of life, and therefore also our true selves. Are we ready to undertake this journey in this lifetime?

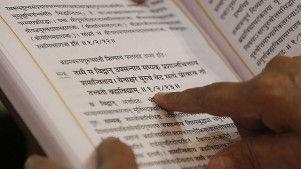

Image Credits: By Vipul Vaghela | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 3.0

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By Vipul Vaghela | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 3.0

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

Article References

(1) Pradipaka, Gabriel. Learning Sanskrit – Verbs – 1 (English). Sanskrit & Sanscrito. < http://www.sanskrit-sanscrito.com.ar/en/appendixes-verbs-appen-verbs-1-english-0/728> (2) The Vedic Foundation. Sanskrit: The Mother of All Languages.

What do you think?