The Art of Healing and Evidence Based Medicine

Article By S. Goodall

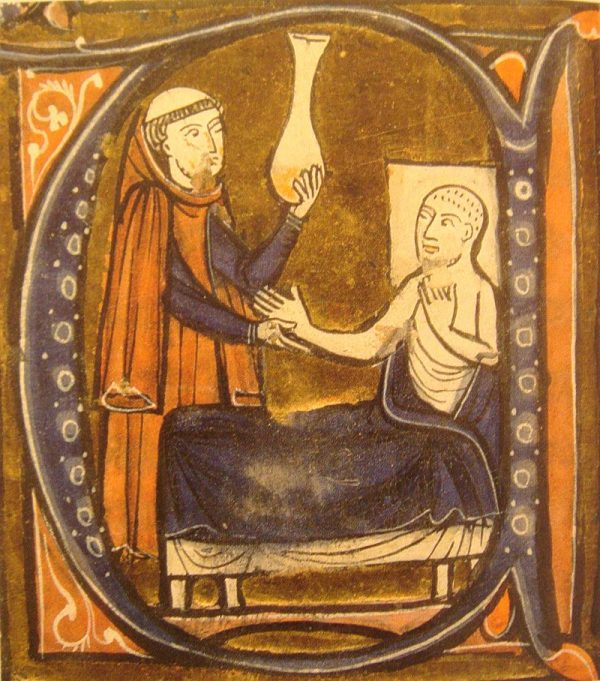

Healing practices have been recorded for millennia across cultures and geographies. Ever since sickness has existed, human beings have developed many different methods and systems to try and facilitate healing, many of them differing in their understanding, approaches and aims.

Healing practices have been recorded for millennia across cultures and geographies. Ever since sickness has existed, human beings have developed many different methods and systems to try and facilitate healing, many of them differing in their understanding, approaches and aims.

Medicine has always been considered partly science and partly art. Part of medicine deals with the scientific knowledge of the body and disease, and the technical methods and equipment used to treat disease. The ‘artistic’ aspect of medicine is perhaps the ability to see the patient as a whole and to be able to connect with him or her.

Over the last century, great material progress has been made by humanity – a greater understanding of the laws and principles of nature, as well as the development of a number of technologies which aim to make our lives easier and more comfortable. However, comfort and pleasure can create cravings for greater comforts and pleasures, diminish stoic values and lessen the use of inherent human capabilities, leading to a loss of human potential and ultimately to a loss of confidence in human nature. This downward spiral gets reflected externally as a lack of faith and crisis of mental and spiritual health, breakdown in trust in societal roles, a sense of confusion and ultimately can lead to anarchy in society.

Along this journey of technological advances, there have also been changes in the way doctors are taught and a shift from a moral to a legal and regulatory basis for medical education and training. This has resulted in the view of the practice of medicine more as a profession than a vocation and the consequent prioritization of efficiency over service. Also, the industrialization and strategic competition among providers of healthcare and allied fields such as pharmaceuticals have led to larger and larger organizations, in which the stakes for survival are constantly growing and high-pressured business decisions are made far away from the bedsides of suffering patients. Such factors have spread internationally and led to a breakdown of trust in doctor-patient relationships across the world. This has consequently led to greater regulation of medical practitioners and an attempt to impose transparency and standardization on clinical practice through the practice of Evidence Based Medicine (EBM), a rational though limited solution.

EBM is meant to be the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. However, although this definition invokes rigour and attention to detail, it makes no reference to compassion or even healing, which is ultimately the aim of all care.

EBM is based on an order of levels of evidence, with level I considered the highest and level VII considered the lowest levels of evidence. In a nutshell, the data and conclusions from well-designed randomised controlled trials and their systematic reviews and meta-analyses are meant to constitute higher levels of evidence, while information from smaller qualitative studies and the opinions of recognized experts are meant to constitute lowest levels of evidence. In practice, approval and funding decisions of a number of policy-making and advisory bodies are based on the quality of such evidence.

The process of obtaining and recording such evidence is meant to be rigorous in technique and involves significant resources and expense, which limits what can be studied in such a way. However, the interpretation and reporting of such evidence can be more subjective and even self-interested. Philosophically, objectivity is never absolute, but it needs a great sense of openness, humility and wisdom to accept this. EBM can lead to an emphasis on ‘cold statistics’, away from ambiguity of application in the real world – the bedside of sufferers.

Thus, though EBM can be a tool to try and ascertain the value of certain medical treatments, there are a number of questions around its validity and scope of use as an overarching and almost exclusive medical paradigm, which is the case today. For example, is the whole truth to be found in numbers? Can we really know a tree just by counting its leaves? Might there not be multiple levels of causation and correspondingly multiple levels of understanding?

As Albert Einstein said, “Not everything that can be counted counts and not everything that counts can be counted”. Though one can only go by one’s current perceptions, would it not be wise to acknowledge that our present understanding is not necessarily a perfect one and that a different way of looking at things may be possible?

For example, does the lack of validation by randomised controlled trials make the use of some treatments from the so-called ‘alternative’ forms of medicine such as homeopathy, less valid? For that matter, even some of the ‘common sense’ and intuitive ‘grandma’s remedies’ for minor ailments may not be supported by evidence, but are commonly used and surely their health benefits in individual cases cannot be doubted.

Although established with good intentions, the EBM culture has put an enormous strain on doctors and seems to prioritise the ‘objective’ science of medicine over the intuitive and more relational art of healing. The time has perhaps come for medicine to recognize that scientific objectivity is not the only basis for its practice, and to find ways in which its compassionate spirit, which is surely at the very origin of medicine, can be placed on at least an equal footing with the prevailing EBM culture.

Image Credits: By Hush Naidoo | Unsplash | CC0

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By Hush Naidoo | Unsplash | CC0

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

What do you think?