The Mysterious Fraternity of the Rosicrucians

Article By Julian Scott

In 1614 and 1615, two ‘Rosicrucian Manifestos’ were published in Germany. They described the foundation of the “Fraternity of the Rosy Cross”, outlined its basic principles and invited learned men of good will to apply for membership and contribute to a “general and universal reformation of the whole wide world”.

In 1614 and 1615, two ‘Rosicrucian Manifestos’ were published in Germany. They described the foundation of the “Fraternity of the Rosy Cross”, outlined its basic principles and invited learned men of good will to apply for membership and contribute to a “general and universal reformation of the whole wide world”.

The first Manifesto, entitled “Fama Fraternitatis (Fame of the Fraternity), tells the story of its prodigious founder “Christian Rosenkreutz”. This no doubt legendary and symbolic tale recounts how, after spending his childhood in a monastery from the age of five, he set off on a journey to the East at the age of sixteen. There, he absorbed all the wisdom of Arabia – ranging from the Cabala (see later), to medicine, mathematics and mechanics, the philosophy of macrocosm and microcosm, and the knowledge of ‘elementary spirits’. Thus filled with wisdom, he returned to the West, enthusiastically wishing to impart his knowledge to the scholars of Europe for the renewal of learning. However, his teachings fell on deaf ears and he retired for five years into solitude, during which time he pursued researches into the secrets of nature and made further discoveries.

After this period of isolation, he again felt the urge to bring about a reformation of the world and gathered around him a number of disciples, who set off for different parts of the world to spread his teachings. At the age of 106 (in the year 1484), he died, or rather, mysteriously disappeared. A hundred years later, his tomb was discovered – a place of marvels containing further revelations – and this was taken as the sign to make his work and teachings public. Thus, the manifestos came to be published and a great interest was awakened throughout Europe in this general reformation of the world and the spiritual doctrines that inspired it.

Although the story is full of mythical elements and is probably not meant to be taken as literally true, the Rosicrucian teachings themselves were quite clear and gave rise to a powerful movement in the 17th century which, as we shall see, affected the religious, political, philosophical and scientific landscape of Europe.

In historical terms, Rosicrucianism has its roots in the Hermetic, Cabalistic and Neoplatonic traditions of the Renaissance, which in turn go back to far more ancient origins, such as the teachings of Pythagoras and Hermes Trismegistus. As to its real founder, there are a number of possible candidates (including Sir Francis Bacon and Giordano Bruno), or perhaps there was no one founder in particular. But for Frances Yates, the scholarly author of The Rosicrucian Enlightenment, the driving force behind the foundation of the Rosicrucian movement in Germany (where it began) was the English philosopher, mathematician and astrologer, John Dee. Dee had travelled to central Europe in the late 16th century and his interests bear all the hallmarks of Rosicrucian thought: Cabala, alchemy, astrology mathematics, mechanics, etc. (For more on John Dee, see The Occult Philosophy in the English Renaissance, in Kairos No. 16).

The Message of the Rosicrucians

The Rosicrucian Manifestos highlight the key aspects of their philosophy as follows:

- The understanding that Man is a Microcosm of the Cosmos – the Macrocosm or totality of the ordered universe.

- The promotion of unity and brotherhood among all human beings, without distinctions of race, creed or social class, particularly among the community of the learned.

- The cultivation of mathematics and mechanics.

- The desire to reform the world and bring about an advancement of learning in all departments of life – education, science, politics, religion, art, etc.

- The practice of medicine, free of charge (doctors take note!); and within this the search for a universal medicine that will cure all the ills of the world.

- The practice of ‘spiritual alchemy’, rejecting the notion of using this art to manufacture gold and become rich.

- The ascent to wisdom in three stages: Philosophy, Cabala and Magic.

- A reformed Christianity.

Let us now look at these aspects one by one, and so gain a more complete picture of the Rosicrucian Way.

Microcosm and Macrocosm

The Rosicrucian Manifestos themselves declare that their philosophy is not new; it is merely a reformulation of knowledge that has existed “since the time of Adam”. The philosophy of macrocosm and microcosm is based on the idea that the Cosmos is a harmonious whole ordered by a Divine Intelligence. Man, too, is a Cosmos, an ordered whole, but a ‘micro-cosmos’, a cosmos in miniature. The human body is a cosmos, and the human mind, potentially, is also a microcosm of the Mind of God. Thus, by studying the human body, one can come to know the great body of nature and the universe; and by knowing the human mind, one can come to know the Mind of God. According to this idea, everything is governed by correspondences; everything is connected. As the Rosicrucian physician Robert Fludd (1574-1637) pointed out, there are sympathies and antipathies in nature, which he described and explained in his work Ultriusque Cosmi Historia, or the History of the Two Worlds (on the harmonies in the Cosmos and in Man). He cites as a rather quaint example of antipathies in nature the antipathy that exists between the cat and the mouse, amongst many other examples.

The Promotion of Unity and Brotherhood

Like all esoteric societies before and after them, the Rosicrucians believed in the unity of God beyond all religious differences, and this is reflected in the fact that they counted both Catholics and Protestants among their members. However, because of the historical circumstances of the time, the majority tended to be Protestant. The reason for this was that the old order of Europe was allied with Catholicism, while the movements for change tended to be associated with Protestantism. However, as Yates points out, the Rosicrucian General Reformation of the World was designed to replace both the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter Reformation, which in the Rosicrucians’ view had both failed.

One of the key mystical works from which the Rosicrucians drew inspiration was The Imitation of Christ by Thomas Kempis (1379-1471), a mystical writer who was associated with a 14th century religious movement called “The Brethren of the Common Life”. As the title of his book suggests, this work places the emphasis on the real application of the virtues shown by Christ, such as love for one’s neighbour, charity, forgiveness and humility, rather than on the divisive dogmas which gave rise to the ‘Wars of Religion’ so prevalent in those days.

Mathematics and Mechanics

The cultivation of mathematics and mechanics was part of what the Rosicrucian physician Robert Fludd called ‘good magic’, which he regarded as an integral part of natural philosophy.

Mathematics is fundamental to the philosophy of macrocosm and microcosm, as taught by Pythagoras and the Hermetic Tradition. It is the study of the harmonic proportions that underlie the order and structure of the universe. As these proportions are present in everything, this study gives rise to the ‘Magna Sciencia’ or ‘Magic’, which is the profound knowledge of the universe and the human being in all aspects.

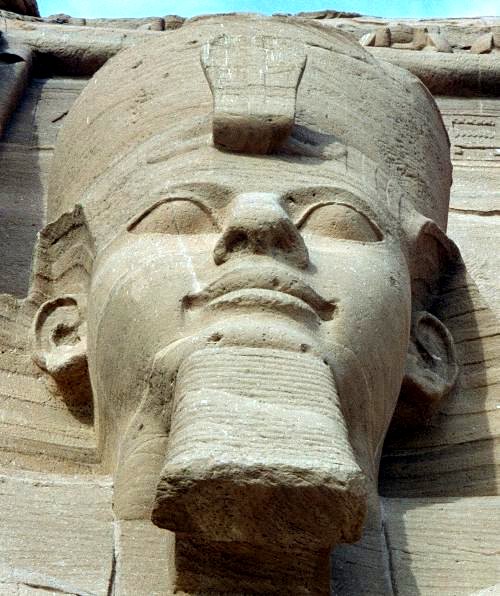

Mechanics is one of the practical applications of this knowledge in useful inventions for mankind. In the 16th and 17th centuries, many mechanical inventions were used in the theatre to produce special effects. The mathematician John Dee was an expert in the creation of such devices, which were so impressive that people thought that he must have been in league with the Devil. Similarly, in the gardens of Heidelberg Castle, in Germany, Rosicrucian ‘mechanicians’ created, amongst other marvels, ‘speaking statues’ operated by hydraulic mechanisms, in imitation of the Colossi of Memnon in ancient Egypt.

There were many other practical applications of this knowledge. Indeed, Frances Yates claims that the foundation and early development of the Royal Society, Britain’s foremost scientific institution, was driven by Rosicrucian influences. She cites as part of her evidence the fact that several of its founders, such as Elias Ashmole (after whom the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford is named), were closely associated with Rosicrucian ideas and practices. She also points out that the most famous second-generation Fellow of the Royal Society, Sir Isaac Newton, was also motivated by these ideas. “As a deeply religious man, like Dee, Newton was profoundly preoccupied by the search for One, for the One God, and for the divine Unity revealed in nature.” It is also now becoming increasingly well known that Newton’s chief scientific interest was alchemy, as Michael White’s biography Isaac Newton, The Last Sorcerer, shows.

How is it, then, that science today has so far forgotten this search for the divine unity revealed in nature and become a bastion of materialistic thought? Yates offers an interesting explanation: while some academicians remained faithful to the Rosicrucian cause and were outspoken in its defence, others, afraid of the association with magic and of incurring the enmity of the magic-hating king, James I of England, disassociated themselves from it by openly attacking such ideas. And the rest is history… It is very interesting to learn that Comenius, a prominent exponent of Rosicrucian ideas, wrote a letter to the Fellows of the Royal Society congratulating them on its foundation, while at the same time warning them of the wrong path they seemed to be taking – “building not towards heaven, but towards earth”.

The General Reformation of the World

Frances Yates has shown in her various books about the Occult Philosophy in the Renaissance that in the 15th and 16th centuries there was a general attempt to reform the European world on the basis of Hermetic principles. Until she came to write her book The Rosicrucian Enlightenment, she had believed that this impulse had died at the end of the 16th century, with the burning at the stake of Giordano Bruno in 1600. However, as she began to research the 17th century, she found that the same impulse had reappeared, in the form of Rosicrucianism, with slight variations, but essentially the same intention – a general reformation of the world based on spiritual philosophical principles.

This desire for reformation could be seen in all areas of life, and she cites the enthusiasm felt by the poet Milton and others in England for a universal reform in education and all departments of life, inspired by Rosicrucian figures like Comenius. Comenius expresses this enthusiasm in his book The Way of Light, written in England in 1641, which includes a prophecy that the Schools of Universal Wisdom advocated by Francis Bacon in his New Atlantis would soon come to be founded. Similarly, we find the Puritan theologian, John Webster, urging that “the philosophy of Hermes revived by the Paracelsian school” should be taught in the universities.

All of this is very much in tune with the 2nd principle of Rosicrucianism as cited by Manly P. Hall in his book The Secret Teachings of All Ages: a reformation of science, philosophy and ethics .

Yates also shows that there was an attempt to bring about a political reform, by establishing and extending a philosophical state (in line with the 1st Rosicrucian principle). This took the form of the brief reign of Frederick V, Elector Palatine and his wife Elizabeth, daughter of James I of England, at Heidelberg. Yates sees it as a kind of model of a Rosicrucian monarchy for which many people in England and Germany had great hopes. However, when on the death of the king of Bohemia, Rudolph II, Frederick was offered and accepted the crown of that country by the Protestant forces, the forces of the Catholic Counter Reformation, allied with the Spanish monarchy, rose up and crushed this potentially benevolent political movement and the young monarchs were hounded into ignominious exile. Yates points out that if Elizabeth of Bohemia had become Queen of England (if her brother, Charles I, had died, as he nearly did), there would probably not have been a civil war in England, because Cromwell was not against monarchy per se, but against monarchs who wanted to rule without parliament and who did not support the Protestant cause in Europe.

While the Rosicrucians’ attempts at religious, political and scientific reform were not entirely successful at the time, history shows that these spiritual impulses never cease, even though they may manifest under different names and forms. Like streams of water, they go underground, re-emerge and go underground again, as the circumstances of the land dictate.

The Search for a Universal Medicine

It was stated in the Rosicrucian Manifestos that members of the Brotherhood should heal the sick, free of charge. In this respect, it is interesting to note that one of the most prominent English Rosicrucians, Robert Fludd (1574-1637), was a medical doctor. The practice of medicine for the good of humanity was a natural consequence of the Rosicrucians’ desire to do good, their pursuit of esoteric knowledge and, in particular, their interest in alchemy. Through the knowledge of the correspondences in nature and the link between nature (the macrocosm) and man (the microcosm), allied with their genuine love for humanity, their natural vocation was medicine, and their ‘patron saint’ was the 16th century physician Paracelsus.

The idea behind the concept of a ‘universal medicine’ is that it is not only physical ailments that need to be healed, but that man’s real disease is spiritual: his disconnection from the divine source of life and the conflict between his lower and higher nature. Once the human being has been healed, the Rosicrucians believed, then all of Nature would return to the universal harmony that was lost with the ‘fall of man’ – because Man is the mediating principle between God and Nature.

Spiritual Alchemy

According to Frances Yates, Rosicrucian alchemy is not so much concerned with the making of gold, as with the spiritual transmutation of the human being from ‘man of lead’ into ‘man of gold’. In Rosicrucian alchemy, she says, “the adept… could move up and down the ladder of creation, from terrestrial matter, through the heavens, to the angels and God.”

As Manly P. Hall writes in his entry on the Rosicrucians in The Secret Teachings of All Ages, “… the alchemical retort symbolizes the womb, [but] it also has a far more significant meaning concealed under the allegory of the second birth.” In other words, it is a symbol of spiritual regeneration (one of the most timeless and universal concepts) and this, he states, is at the heart of the Rosicrucian doctrines: “As regeneration is the key to spiritual existence, they [the Rosicrucians] therefore founded their symbolism upon the rose and the cross, which typify the redemption of man through the union of his lower temporal nature with his higher eternal nature”.

The Rosicrucian symbol of the Rose and the Cross epitomises this sense of spiritual regeneration through sacrifice. As Manly P. Hall writes, “The Masters of the Order hold out the rose as the remote prize, but they impose the cross on those who are entering”. In the same vein, the mystical poet, George Herbert, writing at the same period of history (early to mid-17th century), claimed that the real philosopher’s stone or alchemical ‘tincture’ was the phrase ‘For thy sake’. In other words, it is through absolute purity of intention and unselfish devotion to God and the well-being of others that this spiritual redemption is achieved.

A servant with this clause

Makes drudgery divine;

Who sweeps a room, as for thy laws,

Makes that and the action fine.

The Ascent to Wisdom

The transmutation through inner alchemy is related to another common feature of Rosicrucian thought and practice: Cabala (sometimes written Kabbalah). Cabala is a Jewish mystical system passed down through tradition and later adopted by mystical Christians, particularly at the time of the Renaissance. It is based on the idea that, as the ultimate God is unknowable and mysterious, He (It?) does not create the world directly, but emanates a hierarchy of angels or spiritual beings who carry out the creative process. John Dee, the precursor of Rosicrucianism, spent many years communing with angels and recorded some of his experiences in a spiritual diary. Yates comments: “Dee firmly believed that he had gained contact with good angels from whom he learned advancement in knowledge. This sense of close contact with angels or spiritual beings is the hallmark of the Rosicrucian… it is the angels who are believed to illuminate man’s intellectual activities.” Before dismissing Dee as a crank, it should be remembered that he was the foremost mathematician of his day.

According to Manly P. Hall, there are in the Rosicrucian doctrine three stages of ascent to Wisdom, or true knowledge and understanding. The first is Philosophy (the method of understanding through study, deep thought and scientific research); the second is Cabalism (the knowledge of how to invoke the sacred names of the angels and so converse with them); and the third is ‘Magic’ – which he defines as the ‘language of God’, whereby the adept can communicate directly with God without intermediaries.

A Reformed Christianity

The Rosicrucians, and those in whom they found their inspiration, such as Paracelsus and John Dee, tended to have a strong sense of Christian piety, though not of the conventional kind, because it was mixed with potentially heretical pursuits, such as Cabala, alchemy, astrology and magic. Thus, they were frequently accused of sorcery, witchcraft and magic. As we have seen, their Christianity was very much based on the ‘Imitation of Christ’ and on the Rosicrucian saying “Nothing approaches nearer to God that Unity”. On this basis, they proposed a reformed Christianity incorporating Hermetic, Cabalistic and Alchemical principles.

A Mysterious Fraternity

According to Kenneth Mackenzie, in his entry on Rosicrucianism in the Royal Masonic Cyclopedia, a work frequently referred to by H.P. Blavatsky, the Rosicrucians were a mysterious fraternity of isolated learned individuals “aware of their mutual existence, and corresponding by secret and mysterious writings…” They lived in “solitude and obscurity…” and spent much of their time in divine contemplation, by which they discovered “important physical secrets”. However, “… in times of danger, in centuries of great physical suffering, they emerged from their retreats, with the benevolent object of vanquishing and alleviating the calamities of mankind.”

According to this author, who was a 19th century expert in Freemasonry and Occultism, the Rosicrucians were members of an esoteric body that has existed throughout the ages and whose “true name has never transpired”. It has always laboured for the preservation and advancement of knowledge and “the preservation of human life by the exercise of the healing art.” From time to time, as the quotation in the previous paragraph indicates, its members come into the world in times of great need, either in person or through intermediaries, to attempt to bring about great changes. Even if they fail, through no weakness of their own, but because of the ignorance, greed, weakness and prejudices of humanity, they never give up, because they are motivated by the purest love and compassion – the true spirit of Rosicrucianism and its quest for a ‘universal medicine’.

Whether this interpretation is fact or fiction, the historical fact is that people identifying themselves with the Rosicrucian cause worked in exactly the way Mackenzie describes, living up to the ideal expressed in their emblem of the Rose of Love and the Cross of Sacrifice, and leaving us with an example and an inspiration to follow.

Image Credits: By T.Schweighart | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By T.Schweighart | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

What do you think?