Understanding Gandhi: An Exchange with Dr. Tridip Suhrud

Article By Harianto H Mehta and Manjula Nanavati

As the architect of a non-violent civil disobedience movement that led to the independence of a nation, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi has been hailed as a spirited activist, a courageous freedom fighter, and an astute politician. For his own deeply ascetic lifestyle, uncompromising ethical code, and strict adherence to human values, he won the veneration of masses, a devotion usually reserved for saints, indeed even the title of a Mahatma. His profound influence on world leaders like Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King can be said to have changed the course of history.

As the architect of a non-violent civil disobedience movement that led to the independence of a nation, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi has been hailed as a spirited activist, a courageous freedom fighter, and an astute politician. For his own deeply ascetic lifestyle, uncompromising ethical code, and strict adherence to human values, he won the veneration of masses, a devotion usually reserved for saints, indeed even the title of a Mahatma. His profound influence on world leaders like Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King can be said to have changed the course of history.

To understand the true measure of the man, however, we need to invite reflection. Perhaps by grasping the spirit of his lofty ideals, we might translate Gandhi’s legacy into a practical and enduring tool for transformation and renewal in our times today.

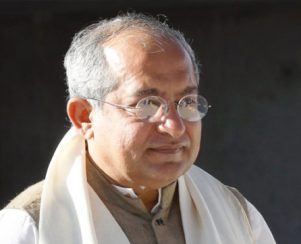

To pay tribute to his relentless pursuit of Truth on the occasion of his 150th Birth Anniversary, The Acropolitan Magazine met with Gandhian Scholar and cultural historian Dr. Tridip Suhrud. As the director of Sabarmati Ashram Preservation and Memorial Trust, he was responsible for creating the Gandhi Heritage Portal, the world’s largest digital archive on Gandhi. He is uniquely fluent in all three languages in which Gandhi wrote, and has authored numerous books, including Beloved Bapu: The Mirabehn-Gandhi Correspondence, as well as a bi-lingual edition of Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj. Presently he is working on translating the Diaries of Manu Gandhi, and a twenty-volume archival project called Letters to Gandhi. Dr. Suhrud is renowned as an authority on Gandhi’s life, his books and his intellectual tradition. Here are excerpts from our conversation.

THE ACROPOLITAN (TA): Gandhiji’s deeply ascetic lifestyle is legendary. He emphasized the need to exercise a rigid self-control on diet, clothing, chastity, medicines; almost to the point of obsession. In your view, what might have been at the root of this degree of self-restraint?

DR. TRIDIP SUHRUD: Simply, it comes from his need to see God face to face. The question is if one can see God face-to-face when one is still in the physical body? His answer is that it will always elude you; no human being can actually see God face-to-face. And yet, unless you have a body, unless you are in the body, you cannot have this desire to see God. This is a standard philosophical problem of the relationship between mind and matter. And Gandhi is aware of it.

But, he says, what we are capable of is, hearing the voice of God, the voice of truth. For Gandhi, there are two requirements to make it possible: the first is the acquired capacity to listen to this voice from within, and the second is the ability to communicate to the world that he is actually acting on behest of this voice.

Gandhi speaks of the voice of Ravan, the untrue, the ego, and the voice of Rama, the truth. In order to be able to discern between these two [inner] voices, to be certain that one is hearing the voice of truth, and not of untruth, one needs to be in control of the senses, of the mind, of the desires.

Unless the senses are in harmony, a person does not acquire, what he calls, a fully developed conscience. And for Gandhi, all desires, whether they emerge from the mind or from the body, are satisfied only through the body. It is really the body which craves, signals satiation or unfulfillment, and feels pain or pleasure. Hence since the body is an impediment, the only way to deal with it is to subjugate the body to the will of the mind, the will of the conscience. If the body acts autonomous of the mind, then you have a problem.

TA: Satyagraha can be translated as Force of Truth, but also connotes civil disobedience, non-cooperation, or passive resistance. But the concept seems to have been used as more than just a political tool. What was the underlying principle that drove satyagraha?

SUHRUD: What is an act of satyagraha? When is it that we do disobedience? Gandhi says I do disobedience when something is repugnant to my conscience and I choose to recognize a higher law.

TA: But could this not be very subjective?

SUHRUD: Of course. Gandhi says that my notion of the truth allows for the fact that I could be wrong. Hence, satyagraha is a process of dialogue.

In any search for truth, you have to make a provision that you could be wrong. Therefore, the question is, can you and I have a relative notion of truth, which then might lead us onto the path of absolute truth? We go back to an old philosophical problem: is truth absolute, or is it relative?

Gandhi’s answer to this is very simple. He says that it is not given to him to understand truth in all its aspects. He is a believer in the Buddhist or Jain notion of truth which says truth has many facets…anekantvada, meaning that there are anek anth, or many possible ends in this search for truth. The truth will always have many different faces, and each person will be able to glimpse only a part of it.

Hence, in the practical terms of satyagraha, there are no non-negotiable stands. A satyagrahi always negotiates. This is not a strategic move. It is a philosophical statement which recognizes that there could be truth in what the other has to say. Even those acting from a large position of injustice, could have truth on their side, or at least a measure of it.

TA: Gandhiji said, “Experience has taught me that civility is the most difficult part of satyagraha.” What really is civility in the context of satyagraha?

SUHRUD: Civility of two kinds. Firstly, one must recognize that there could be truth available to you which is not available to me. Therefore, I recognize that you are just as capable as I, of recognizing and acting upon truth. Now if I say that you are neither capable of recognizing truth nor of acting upon its recognition, then what is the point of satyagraha? You will be blind to any truth that I present to you.

Therefore, civility is that I recognize your humanity. Satyagraha is the only form of protest which recognizes the humanity of others. And that is why there is no notion of pure evil in Gandhi’s world view. That Gandhi is always willing to talk to the British Empire comes from the idea that even the Empire is capable of recognizing the truth. And that if it has become dark one can re-awaken it with some light.

TA: How does one foster this civility, or reawaken this light, this attitude of looking for, and allowing for, truth?

SUHRUD: By conduct, by example. Therefore, the notion of the exemplar.

TA: Gandhi recognizes such an obligation of an exemplary leader?

SUHRUD: All the time. And this is not only true of Gandhi. For anybody who seeks reform, change must begin with oneself. I mean, if I am asking you to consume less…I must first consume less. If I am asking you to stop being exploitative, I must first consider if my own relationships are exploitative. If I am asking you to go to jail for the sake of freedom, am I also willing to go to jail for the sake of freedom?

He says that leading others becomes possible only when you are able to lead yourself, and if you are able to constantly reduce the gap between your words and your deeds.

TA: Leadership can be a very complex issue. Since life is not black and white, it must involve spiritual and ethical dilemmas. What were some of these moral dilemmas and how did Gandhiji resolve them?

SUHRUD: The notion of non-violence, for example, is very problematic. What is it that we are supposed to do if the police come charging at us? Even though the law recognizes self-defence, Gandhi questions whether a satyagrahi can defend himself or herself. And if the answer is yes, then are any and all means justified? Meaning, can I, in self-defence, attack my assailant? Gandhi says: No – a true satyagrahi does not defend himself or herself.

TA: So, what is the right course of action in such a situation?

SUHRUD: Nothing. You stand and are beaten. And you are beaten to that point till the other person sees the invalidity of his violence.

TA: Is there not a dignity involved in standing for justice? By not doing anything and by being beaten down, one is not really proactively endorsing what is needed or what is just.

SUHRUD: Gandhi takes a completely contrary view. The role of a satyagrahi is to say to the oppressor, “Do your worst. If taking my life is going to satisfy your need for violence then go right ahead…do it.” This is a very extreme position on violence and it’s not that it was not practiced by him.

One of his greatest acts of defiance was the picketing that happened at the Dharasana Salt Mines in 1930. Satyagrahis walked up to the barbed wire fence that protected the salt pans, and were beaten down, day in and day out, for weeks! We know through medical records, that of all the people who suffered injuries, not one had fractured fingers or arms. They all had fractured skulls or fractured shoulders. Gandhi had told these workers not to raise a single hand to ward off any blows, not even to protect the skull. He believed that the only answer to that kind of violence could be perfect non-violence.

It was in the ensuing international publicity that the legitimacy of British rule over India was snatched away. The world came to believe that this act of complete non-violence on the part of Indians proved the futility of the use of violence as a legitimate means of subjugating people.

TA: In other words, a civilized world cannot justify the use of uncivilized means?

SUHRUD: Yes. The question really is what is the relationship between means and ends? We have come to believe that if the end is good it does not matter what means we employ. We want freedom and we shall have it at any cost. Gandhi says no. There is an inviolable relationship between means and ends. Means are like seeds which tell us what kind of fruits we are going to have. So, if you create your freedom though an act of violence, then violence becomes a legitimate means for that society, which cannot then aspire to be a non-violent, non-exploitative, just society. When at the root it is believed that all means are justified, what is to prevent the new state from also acting in an unjust way towards its own people?

Every collective believes that its ends are noble. Even those people who go out and lynch people think that their goal is noble because they are protecting the cow and so will employ any means possible. That’s the argument, right? Gandhi says this is exactly what happens if violence and exploitation become a just means.

TA: Gandhiji spoke of “True civilization as that mode of conduct which points out to man the path of duty.” He does not emphasize inalienable rights, but obligatory duties. What kind of duties was Gandhiji referring to?

SUHRUD: Gandhi would say that we will not be violent. We will not be exploitative. We will create conditions where each human being is able to try to realize her potential. If nothing else, it is our duty to create enabling conditions, or what is called trusteeship; not out of compulsion, but out of moral obligation or duty, which is the basis of all philanthropic work. You cannot have philanthropy or trusteeship, if you do not have a notion of duty.

The fact that there is now a Corporate Social Responsibility Law is a signal to us that the wealthy in our country have forgotten this notion of duty. If everybody performed their duties to fellow human beings, then there would not have been a need for enforced CSR, or enforcement of duty. So, I don’t necessarily think that CSR is a great sign of our merit; in fact, for me it is a sign of a lack of merit.

This notion of duty is fundamental to any society. I don’t think you can have a society, without any notion of obligations that we have towards each other. Now, your rights are justiciable, your duties are not, and that’s a very important distinction.

TA: Is this Gandhi being a little bit naïve? Because usually, the duties we perform are quite personal.

SUHRUD: No, he is not. What is personal? The notion of the personal keeps expanding for all of us, doesn’t it? For example, we all say, “This my City.” The fact that you would be concerned about the environment – is that personal? Of course it is. You are saying that the concern for the environment belongs to me, as well as to those who shall succeed me. And therefore, the idea of what is mine can actually potentially include the generation yet to come.

TA: Is it also Gandhi’s understanding that a citizen is obligated to widen the scope of his so-called personal duty?

SUHRUD: Yes. For example, what comprises the personal for a leader?

TA: All those that he leads are part of his personal.

SUHRUD: Exactly. So, can the leader therefore promote his family?

TA: Not at the cost of all those that he leads.

SUHRUD: Exactly. We recognize that. And we take inspiration from leaders like Gandhi who constantly widen the notion of what is their ambit of duty, thereby including the dispossessed within it.

TA: Gandhiji was outspoken about his anguish over modern civilization. He advocated an exacting way of life, and made many controversial statements especially in Hind Swaraj, where he speaks out strongly against lawyers, doctors, hospitals, railways. In his rallying cry to go back to our roots, what was Gandhiji trying to illuminate and revive?

SUHRUD: I don’t think people should take Hind Swaraj literally. We forget that it is a philosophical text. It’s not a programmatic text.

You have to understand that it was written at a time when what we call modernity was not yet a fact. When Gandhi was writing in 1908, modernity was only one of the possibilities. There was actually a larger life outside of modernity, and today what we call primitive was really the norm.

Gandhi says that modernity shifts the focus of human worth outside the human being, into objects. Philosophically it transfers the notion of human goodness or human virtue into an object, what today we call consumerism. That’s One.

Two – we have to recognize that colonialism was tied together with modernity. Industrialization was not possible without the colonial structure which supported it. What were the two forms of knowledge which came to India as part of modern Western education? Law and Medicine. That we will be governed by laws, laws that are not our own, is something that became possible through our participation in the legal framework.

TA: What you’re saying then, is that when Gandhi speaks out against hospitals and railways, he’s using them as symbols…

SUHRUD: They are metaphors. The railway was seen in India, for a very long time as the first modern artefact of industrial production. Even today we think that railways are a sign of progress, right? If your town acquires a good metro system you are likely to re-elect that government, because it is seen as a sign of progress.

TA: But is it not progress in our context?

SUHRUD: But is it the only thing? I mean, although it is something which we require, it does not become the measure of progress. One could argue that it is a sign of regression, having resulted in lop-sided growth and created these unmanageable cities. If you actually had more balanced growth, Bombay would have been liveable, and Delhi would have been breathable.

TA: What should be the relationship of modern India’s youth to Gandhi today?

SUHRUD: It cannot be an easy relationship; he is not an easy character to relate to. But my thinking is very simple. If you are unhappy with the world in which you live, if you think there is injustice, poverty and hunger that we are unable to explain even to ourselves, then you need to engage with India. And one of the persons who would allow you to engage with India deeply is Gandhi.

In what I call normal times, we don’t want to engage with anyone who asks uncomfortable moral questions, and that has been exactly the relationship that India has had with him. It’s only in times of crisis that we turn towards Gandhi. And at those times, he can be a great ally in showing us how to make individual and collective lives better.

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsPermissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

Excellent.

A careful conscientious researcher, and communicator, Dr Tridip puts Gandhian perspective perfectly across to both students and scholars.