Aristotle – the Ethics of Happiness

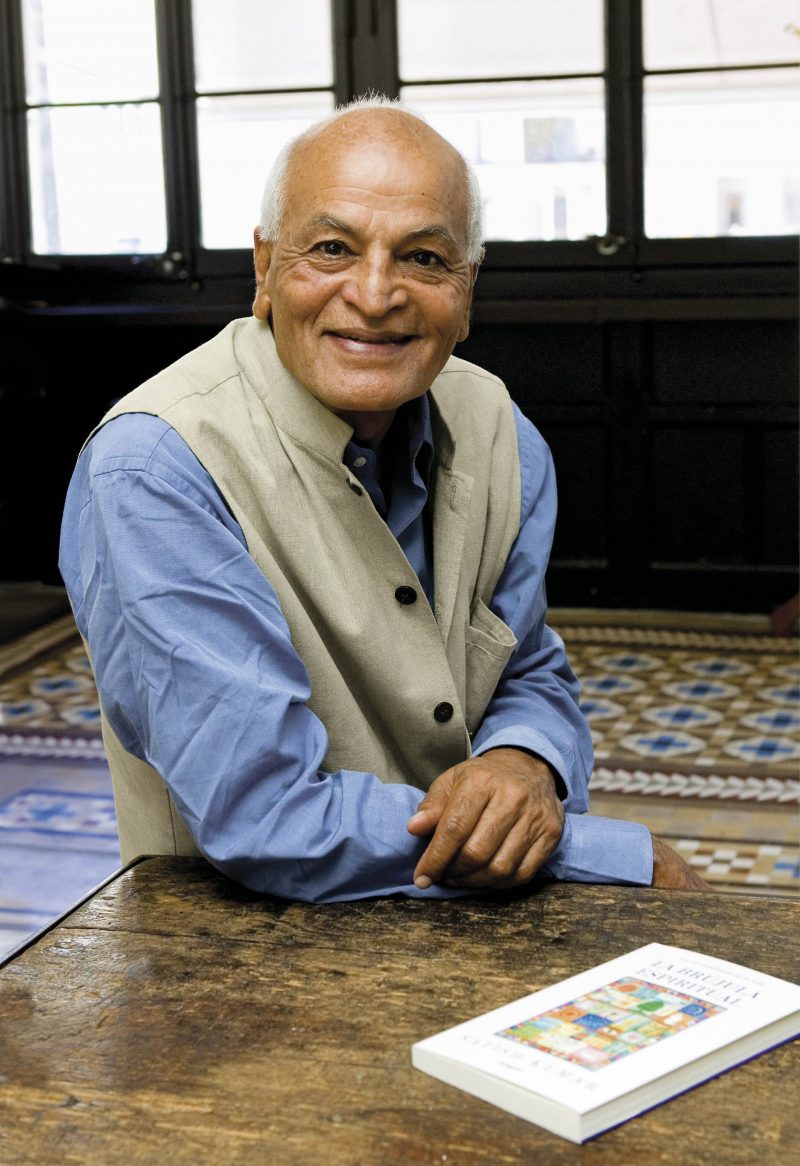

Article By Julian Scott

One of Aristotle’s most famous works is his Nicomachean Ethics, so called because the work was edited by Aristotle’s son Nicomachus. It is a curious fact that none of Aristotle’s surviving works were directly written by him. They are all compilations from his lecture notes, edited by his various students. This accounts for their often dry style, in contrast to the writing style of his lost Dialogues, described by Cicero as a ‘golden stream of eloquence’.

One of Aristotle’s most famous works is his Nicomachean Ethics, so called because the work was edited by Aristotle’s son Nicomachus. It is a curious fact that none of Aristotle’s surviving works were directly written by him. They are all compilations from his lecture notes, edited by his various students. This accounts for their often dry style, in contrast to the writing style of his lost Dialogues, described by Cicero as a ‘golden stream of eloquence’.

The book is in fact a political work, because he begins the discussion by stating that, in order to do his work well a politician must know about the soul of the human being and about what is the good. I wonder how many politicians today think about these questions? This is one of the advantages of reading works of classical philosophy: they give us another, often timeless, perspective on things that still affect us today.

Aristotle proposes that we have three interrelated souls within us: a vegetative soul, which is ‘irrational’ and instinctive and looks after our nutrition and growth; an animal soul, which is concerned with perception and sensation; and finally a rational soul which is the distinctively human part of the human being and is concerned with understanding and living well.

As regards what is good for the human being, Aristotle admits there are many goods which can vary according to temperament and circumstance. For one who is poor, wealth seems to be the ultimate good, while for someone who is ill, good health is their goal. But there is one good that all human beings aspire to regardless of circumstances, and that is happiness

Happiness for a human being must be related to the distinctively human function of reason. So happiness must consist in activities that are in accordance with this reasoning faculty: virtuous activities and ‘contemplation’ or deep thinking. At all times and in all circumstances of our lives we can practise virtue and we can reflect on life.

Perhaps the greatest “discovery” of Aristotle in this field is his almost mathematical definition of virtue (which in Greek means ‘excellence’). It is always a middle point, or “mean”, between two extremes: one of excess and another of deficiency. So, for example, courage is a mean between foolhardiness and cowardice. Moreover, virtue must always be in the right measure: neither too much nor too little, at the right time, with regard to the right person or thing, with the right motive and in the right way. Thus, to act virtuously is not just about ‘being good’, it is to become an expert in the art of living. It is as difficult as hitting a target in archery, while to act without virtue or excellence is as easy as missing the target. Hence his recommendation in most cases to follow the way of the difficult, rather than the way of the pleasurable.

The good news is that virtues can be acquired; we are not stuck with whatever we are born with. They can be developed following the simple principle that ‘practice makes perfect’. In Aristotle’s own words: “We become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, brave by doing brave acts.” We should not expect immediate results, however, but regard the acquisition of virtue as a lifetime’s practice.

With regard to the practice of contemplation (the second key to happiness), this means that apart from acting we also need to reflect: on the events of our lives and those of others, on history, politics, the nature of the universe… This activity also enriches human life and leads to a serene and truly human happiness, which will help us to cope better with misfortune.

With this, Aristotle brings his argument full circle and returns to politics. Now that we know, he says, what the human being is and what is the good for a human being, we can look at which type of political system would be best for the wellbeing of all, a subject he will deal with in his sequel to this work, the Politics.

Image Credits: By Nick Thompson | Flickr | CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By Nick Thompson | Flickr | CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

What do you think?