Rodin and the Art of Ancient Greece: the transcendent reality of sculpture

Article By Siobhan Cait Farrar

This Spring, the British Museum opened the exhibition ‘Rodin and the Art of Ancient Greece’, which formed a poetic tripartite tribute to the artist, his love of ancient Greek sculpture and of the British Museum itself − Rodin famously spent hours studying the museum collections.

This Spring, the British Museum opened the exhibition ‘Rodin and the Art of Ancient Greece’, which formed a poetic tripartite tribute to the artist, his love of ancient Greek sculpture and of the British Museum itself − Rodin famously spent hours studying the museum collections.

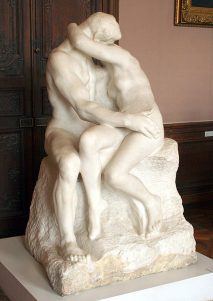

Side by side were maquettes, marbles and famous bronzes of Rodin next to stunning examples from the Parthenon marbles, all displayed at eye level and allowing for a starkly intimate search of their folds, subtle gestures and characters. Opening the exhibition was Rodin’s ‘The Kiss’ caught in spatial dialogue with two ancient Greek Goddesses also intertwined in repose. Being able to hold, in a single gaze, these two works, which whilst straddled across thousands of years are evidently tethered, created a curious flattening of time. In the company of Rodin’s sculptures, the Parthenon pieces were also revitalised and rejuvenated individually. Gone from the mind were any of the clichés which all too readily attach themselves to classical works, as was any over-familiarity that can make Rodin difficult to appreciate. Instead, placed next to one another, the works appeared to echo each other, as if to say, ‘we were formed by related minds’. They seemed able to speak to the viewer of transcendence, of the years that lapped between their feet and of the most mysterious dimension of time, of movement and permanence.

“No artist will ever surpass Pheidias… The greatest of the sculptors, who appeared at the time when the entire human dream could be contained in a pediment of a temple, will never be equalled.” – Rodin

Rodin clearly admired the art of the ancient Greeks but he was also hugely influenced by the Italian Renaissance, Michelangelo and Donatello in particular. He spent three months in Italy, visiting Rome, Venice, Florence and Naples. From Italy he incorporated the Renaissance idea of working on the naked body before adding clothing to the final piece or image − a technique also used by Raphael. The artist first draws or sculpts the naked body, intimately knowing the musculature and peculiarities of their figures, their journey through life; and in each muscle, in each ligament and each vein, the artist imbues the body with character. The resulting works, in both Renaissance art and with Rodin, present depictions of living, breathing, archetypal human souls.

“The body is a cast that bears the imprint of our passions” – Rodin

In the exhibition we were fortunate to see the naked casts which eventually became one of The Burghers of Calais, a six-figure, life-size bronze which forms the climax of the exhibition. The Burghers of Calais is a tale of courage, sacrifice, human struggle and redemption, a complex meditation preserved in bronze, whose archetypal figures are ready to tell their stories and speak with us at a given glance.

There is a transcendental line of mastery from the ancient Greek sculpture of Phidias, echoed in the Renaissance by Michelangelo and articulated again by Rodin. The sculpture acts as an allegory of the human being and a true mirror of our human nature. Like us, a sculpture must be able to endure and speak of what and who it is within the turbulent movements and decaying forces of time. And like us, wherever a spark of clarity becomes visible, even in the smallest fragment, we can recognise the nature of the whole.

“…they are no less masterpieces for being incomplete” – Rodin

Image Credits: By Szilas | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By Szilas | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

What do you think?