The Ancient City of Alexandria

Article By Nataliya Petlevych

Once there was a city known as “the greatest emporium in the whole world” (Strabo, Geography). For generation after generation it attracted the finest scholars, philosophers, poets and inventors. It was a truly international centre that brought together Egyptians, Greeks and Jews, as well as Babylonians, Persians, Gauls, Phoenicians and Romans. In a spirit of tolerance, they worked towards advances in the knowledge and culture of the ancient world, including mathematics, astronomy and astrology, alchemy, optics, medicine and anatomy, grammar and literature, geography, philosophy and theology.

Once there was a city known as “the greatest emporium in the whole world” (Strabo, Geography). For generation after generation it attracted the finest scholars, philosophers, poets and inventors. It was a truly international centre that brought together Egyptians, Greeks and Jews, as well as Babylonians, Persians, Gauls, Phoenicians and Romans. In a spirit of tolerance, they worked towards advances in the knowledge and culture of the ancient world, including mathematics, astronomy and astrology, alchemy, optics, medicine and anatomy, grammar and literature, geography, philosophy and theology.

Its name was Alexandria and its glorious history started with the dream of one remarkable individual: Alexander the Great. Under Alexander’s orders, its first outline was traced in the sand near the ancient settlement of Rhakotis on the Mediterranean coast in 331 BCE. However, the city’s construction was carried out mainly under the direction of Alexander’s childhood friend, confidant and senior general, Ptolemy, who became Ptolemy I Soter (“Saviour”) of Egypt and the founder of the Ptolemaic dynasty that revived ancient Egypt for the last time and ensured the transition of its heritage into the new historic era. Alexandria became the capital of Egypt and the place where the Egyptian and Greek cultures fused and created something new and unique.

Ptolemy II Philadelphus (283-246 BCE) and Ptolemy III Euergetes (246–221 BCE) continued building and developing the great city. They managed to create such a powerful centre of administration and commerce, a truly cosmopolitan cradle of wisdom and culture, that it continued to enrich the world for many centuries afterwards in spite of any political, economic or social turmoil. The heart of the cradle was the Alexandrian Museum and the Serapeum (temple of Serapis), both of which had libraries: the main Library of Alexandria being a part of the former, and a smaller “daughter” library part of the latter.

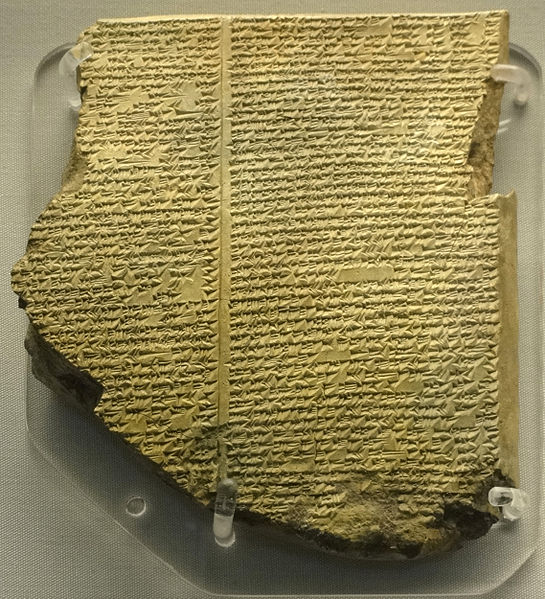

The Ptolemies intended to gather in their city all sacred, philosophical, scientific and literary works of the world (even Hindu and Buddhist texts from India could be found there). To that end, no cost or effort was ever spared. As a result, the library’s contents have been estimated at around three-quarters of a million scrolls (1 scroll = 2000 lines). But its value lay not only in its contents. In addition to the grand collections of works, it had lecture halls, meeting rooms and gardens, and together with the Museum (a study and research institution) formed a veritable sanctuary of thought and home to the most famous thinkers of the ancient world.

The members of the Museum were provided with a large salary, free food and lodging, and exemption from taxes. It was here that in the 3rd century BCE Eratosthenes of Cyrene developed a method for finding prime numbers (“The Sieve of Eratosthenes”), calculated the circumference of the Earth with minor error, developed a method for drawing accurate maps of the world and wrote the first chronological history of Greece; Aristarchus of Samos theorised the heliocentric solar system; Archimedes possibly studied and invented the “Archimedean screw”; the father of geometry, Euclid of Alexandria, wrote his Elements; Zenodotus of Ephesus established the canonical texts for the Homeric poems and the early Greek lyric poets; and Callimachus produced his 120-volume Pinakes, the bibliographic survey of the contents of the Library. Later, during Roman times, many practical inventions were made on the basis of knowledge accumulated in the Library, including the first steam engine, a vending machine, and concrete, especially for use underwater.

Many other important works were conducted at the Museum, including numerous translations from Egyptian, Hebrew and other languages, philosophical studies that considerably influenced Christianity and also produced a school of Neoplatonists. The Museum truly implemented its symbolic meaning – a place where the muses, goddesses of literature, science and art, live and inspire the pursuit of knowledge and wisdom and make the flourishing of civilization possible.

The will, genius and generosity of the founder, the first rulers of Alexandria and all the members of the Museum extended the boundaries of knowledge and the possibilities of the human spirit. Sadly, much of its heritage was destroyed and had to be achieved again from the 16th century. What would the world look like now if tolerance and love of wisdom had prevailed and the transition from the ancient world had been allowed to take place without the destruction of the gifts of Alexandria?

Image Credits: By ASaber91 | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 4.0

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By ASaber91 | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 4.0

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

What do you think?