The Ancient Stoics Come to our Aid Today

Article By Delia Steinberg Guzmán

As a result of the number of adverse situations we have to face, many health professionals are having to propose solutions to deal with the ever-increasing number of cases of uncontrolled and unmanageable emotions, depressions or, on a smaller scale, states of anxiety.

As a result of the number of adverse situations we have to face, many health professionals are having to propose solutions to deal with the ever-increasing number of cases of uncontrolled and unmanageable emotions, depressions or, on a smaller scale, states of anxiety.

It is interesting that this has led us to turn to the ancient world for answers which have been useful and positive in the past. This is the case of the Stoics, who have been recovered as a tool for helping with our current conditions.

Many books and articles have been written and continue to be written on the subject, when not directly quoting the advice of those philosophers. One such work was recently brought to my attention; it is called Philosophy for Life and Other Dangerous Situations: Ancient Philosophy for Modern Problems, by Jules Evans.

I would like to highlight some truly interesting ideas:

-

It is not events that make us suffer, but how we see them.

Our approach to events is very important. Our mental and emotional position can completely change what they mean to us, which is equivalent to saying that it would be simpler if we changed our approaches to them.

Often, the way we see life depends on beliefs and opinions that have become rooted and hardened inside us, even though they are not exactly our own; they come from outside and silently infect us.

We need a new attitude that will allow us to expand our limits and horizons, not in order to be happy once and for all, but at least to be calmer and more serene, knowing that we will eventually find a way to alleviate the sufferings.

Serenity is an essential factor. We have to learn how to calm ourselves, to see and listen within without over-excitement or pain.

-

We are not always conscious of our opinions, but we can sincerely investigate within ourselves until they become clear.

The ancient Greek philosophers, including Socrates, affirmed that it is indispensable to know ourselves, and to do this we need to make a sincere and continuous examination without becoming obsessive. We must learn to ask ourselves about what we like and don’t like, what we believe and reject, what attracts us and what upsets us.

A very useful piece of advice from the Stoics is to write short diaries with reflections about our thoughts and feelings, analysing ourselves honestly and briefly.

-

We cannot control what happens, but we can control our reactions to events.

The Greek philosopher Epictetus divided human experiences into two types: the things that depend on us and those that don’t. Those that don’t depend on us are innumerable: human, social, economic, climatic factors, in general pain, death… and so many others which are equally unpredictable.

But what does depend on us is the control we exercise over ourselves, above all if we make it a constant practice. Self-control supports self-affirmation, reduces anxiety and fosters the ability to make our own decisions in confusing situations.

-

Choosing the perspective.

We referred before to the approach to things, and now we want to refer to the perspective. Perspective reflects the angle from which we approach things, how we give them more or less value depending on whether or not they are in our sights. Take the case of a good photographer who knows how to choose details that go unnoticed by others, but which he is able to highlight.

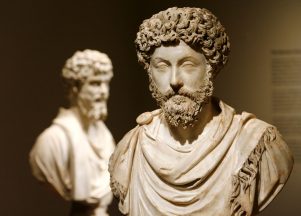

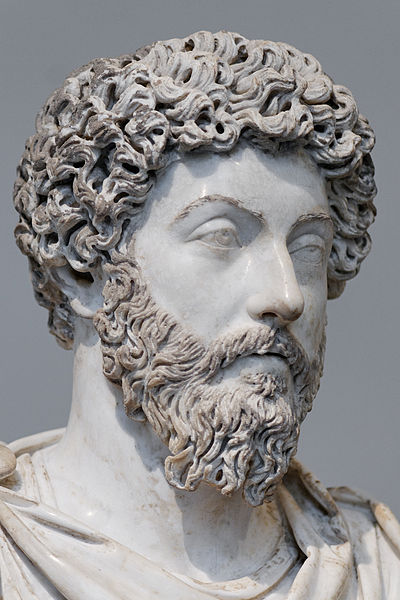

The philosopher-emperor Marcus Aurelius liked to compare the human condition with the immensity of the universe because it enabled him to take a more simple and humble perspective. In one of his examples he states: “Nothing happens to anybody which he is not fitted by nature to bear.” In this way, our problems are kept in proportion.

It is also essential to live in the present: there is no point going over the past, which is already past, except in order to extract the valid experiences; and there is no point fantasising about the future when we don’t even dare to properly plan a day, a week, or a month of our lives.

-

The importance of conscious repetition.

The Stoics give a lot of importance (as do other modern philosophical tendencies) to teaching, to continuous exercise, to conscious practice and repetition; if we only repeat mechanical actions we won’t extract any valid learning.

-

The importance of work.

Inaction is the mother of all evils. Work, both physical and mental, enriches the human being, not only because it productively occupies his time, but also because it shows him fields of action to which he can return in moments of despondency. Seneca said: “the Stoics see all adversities as a training exercise”. This indicates that obstacles should be turned into trials and be recognised as such so that we can extract a teaching from them which will be useful for the whole of our lives.

-

The importance of virtue for attaining happiness.

Stoicism aimed at a state of well-being which is based on the values of virtue. More than well-being, human beings are constantly looking for happiness, although happiness is not the same for all. For the Stoics, there can be no happiness in external factors, which are as variable as wealth and power, but only in inner development.

Although it may seem very hard to detach oneself from worldly and prestigious goals, it is not so hard when we discover the value of the inner treasures that no one can take away from us.

-

The importance of ethical obligations towards humanity.

Human ethics proposes obligations that need to be fulfilled towards all those around us: friends, family, colleagues and life partners; but there is a wider duty which includes the whole of humanity, because we form part of it.

These different obligations may be very difficult to combine on many occasions, but our skill lies in finding points of confluence and not of friction.

For some powerful reason, the Stoics thought of people as “citizens of the world”, without neglecting love for one’s own country. But the world citizen also thinks of the whole in order to look for a happiness which is beneficial for all.

Image Credits: By Bob3321 | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 4.0

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By Bob3321 | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 4.0

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

What do you think?