Titian: Combining the Sensual with the Divine

Article By Siobhan Farrar

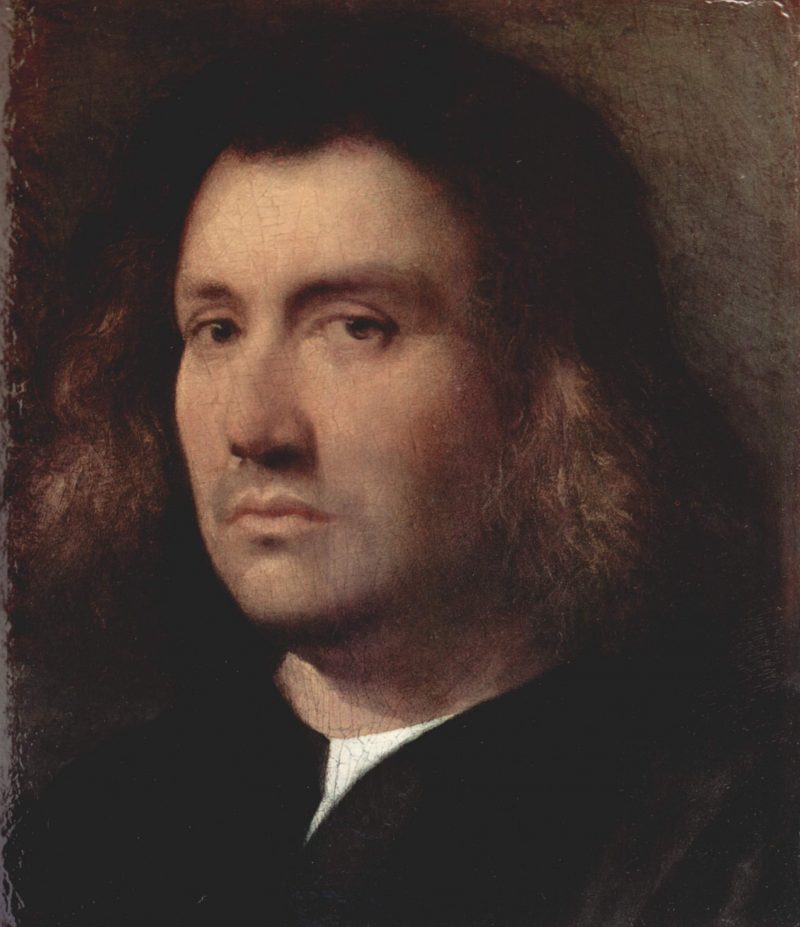

Titian (c. 1488-1576) is arguably the greatest Venetian painter of the Italian Renaissance, who earned European-wide fame and recognition during his own lifetime. The collection of paintings referred to as his ‘poesies’ (a name he coined himself) delineate poetic pictures or poetry produced in painting and draw upon the Roman poet Ovid’s classic epic, Metamorphoses (c. 20 BCE). Originally produced for Prince Philip of Spain (the future King Philip II), they have been brought together in London’s National Gallery for the first time in 450 years.

Titian (c. 1488-1576) is arguably the greatest Venetian painter of the Italian Renaissance, who earned European-wide fame and recognition during his own lifetime. The collection of paintings referred to as his ‘poesies’ (a name he coined himself) delineate poetic pictures or poetry produced in painting and draw upon the Roman poet Ovid’s classic epic, Metamorphoses (c. 20 BCE). Originally produced for Prince Philip of Spain (the future King Philip II), they have been brought together in London’s National Gallery for the first time in 450 years.

Renaissance Humanism understood poetry, painting and philosophy as aspiring towards the same ineffable source. The gifted artist was considered to be in possession of unusual imaginative and intuitive capabilities, the gifted poet in possession of extraordinary powers of thought, the philosopher perhaps a modest combination of both… “It appears from this that philosophers are also painters and poets, and poets are painters and philosophers” – Giordano Bruno.

The arts of the Renaissance, along with its philosophy, were characterised by a rediscovery of the great works and ideas of the classical world. It is easy to forget, but for some time following the fall of the Roman Empire, civilised Europe had all but ceased to exist. The inhabitants of its ruins believed the great temples and structures under which they dwelt to have been put there by mythical giants… Fortunately Europe steadied itself during the Middle Ages and then, with the further rediscovery of the classical world in the Renaissance, came a searing vitality and confidence, an attitude of exploration, innovation and mastery.

Titian was at the centre of the Renaissance Mediterranean world; he had access to the best materials and pigments via the Venetian merchant traders and composed in vivid colour upon the canvas. His innovative loose brush style has come to be seen as a precursor to later art movements such as impressionism and expressionism and he greatly influenced masters like Rubens and Bernini. Up-close the canvases are a sea of expressive colour and tactile brush work, but stepping a little further back the images reveal themselves in a magical transformation of luminescent clarity, where paint recedes and pools of water, glass, stone, and warm golden sunlight emerge.

Titian didn’t construct designs in the same way as some of his Florentine contemporaries like Michelangelo would have done; rather he expressed, wrestled and reworked, lifting his forms out of a world of colour. Perhaps for these reasons Titian doesn’t strictly adhere to the Platonic notion of art and poetry – as something which fully transcends sensuous passion, as undoubtedly in the women of Titian a palpable seduction and power is present. However, earthly power is not the aim or essence of the poetry in these paintings and they trace higher octaves in their contemplation of love, desire, transformation and death. In each, we are witness to an intimate scene from mythology, such as the conception of Perseus via the golden shower of Jupiter on the reclining Danae, or the transfiguration and death of Actaeon, devoured by his own hounds… Then beyond these scenes, in the distant landscapes we glimpse the skyline of a civilisation that could easily belong to our own times. The transcendent scenes of heroes and goddesses look as though they could be taking place on our own horizons, continuously at any moment in history…

In Renaissance Humanism, where art, poetry, myth, intellect and the struggle of life coalesce, the scenes of mythology perhaps do take place at the shorelines of our own lives. Through the ‘poesies’ Titian appears as an artist wrestling and channelling the sensuous into the mythological and divine, drawing these worlds into one another as they are drawn together in human life.

Image Credits: By National Gallery | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By National Gallery | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

What do you think?