Tutankhamun in London

Article By Florimond Krins

Probably the most famous of ancient Egypt’s pharaohs today, Tutankhamun was a small and short-lived king, who reigned for only ten years and died at the age of 18, in marked contrast to the later Ramses the Great, who reigned for 66 years and died in his nineties.

Probably the most famous of ancient Egypt’s pharaohs today, Tutankhamun was a small and short-lived king, who reigned for only ten years and died at the age of 18, in marked contrast to the later Ramses the Great, who reigned for 66 years and died in his nineties.

Tutankhamun (1342 1325 BC) was one of the last pharaohs of the 18th dynasty, who lived during a period of theological and political turmoil. His father, the pharaoh Akhenaton (1352 1336 BC), also called the heretic pharaoh, tried to change the ancient polytheistic Egyptian religion into a monotheistic one, venerating the god of the sun disk, Aten. At Akhenaton’s death the priests of the god Amon in Luxor re-established the old ways through his son Tutankhaten, who was renamed Tutankhamun.

The discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb by Howard Carter in 1922 was a miracle for many reasons. The location was unexpected and discovered by chance by a local water carrier. The tomb is also an amazingly preserved time capsule of ancient Egypt. Most tombs had been looted and left with only the paintings and carvings on the wall to tell their story, whereas the tomb of Tutankhamun contained over 5,000 perfectly preserved artefacts, including the pharaoh’s intact mummy, which is now back in his tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

An exhibition currently showing at the Saatchi Gallery in London offers an enchanting introduction to the life and beliefs of the ancient Egyptians, with hundreds of artefacts on display. Usually, to be able to see them you would have to travel thousands of miles to Cairo.

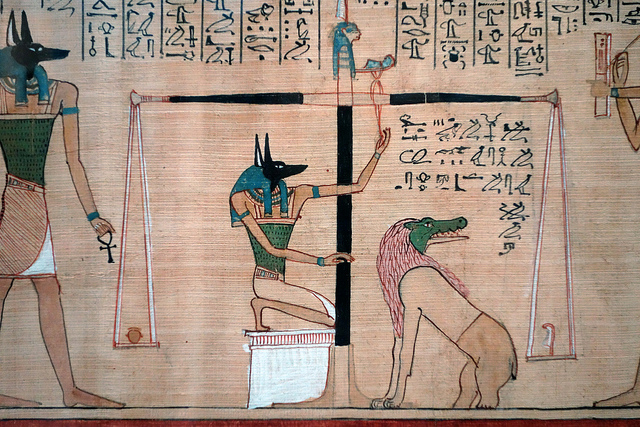

The layout of the exhibition is wonderfully done, allowing you to immerse yourself in a different time and space: a time when the invisible was made visible in the most exquisite ways; a time when the gods, divine expressions of the laws of nature, would meet human beings and teach them. It was the role of the pharaoh and the high priest to transmit those teachings and ensure that Maat, the principle of universal order and justice, would be followed in Egypt.

The tomb of Tutankhamun also gave us also a complete description of the burial and mummification process, as all the canopic jars, in which the organs of the pharaoh were preserved, and the various sarcophagi in which the mummy was encased, were found intact.

Walking through the exhibition, one becomes aware of the importance that the ancient Egyptians gave to the divine and the afterlife. One of the first things a pharaoh did after he was crowned was to start work on the construction of his tomb. But the tomb was never meant to be discovered or displayed, as it was designed to work in the invisible world, allowing the Pharaoh to pass successfully through the gates of the underworld and perhaps also to continue serving and protecting Egypt after his death (there are too many theories on the function of the Egyptian tombs to go into here). For the ancient Egyptians the most important things in life were to be found in the invisible dimension, that of the sacred and the divine; and for them a life was well lived if it prepared them for death and the afterlife. Perhaps something for us to learn from this fascinating civilisation, as we rush here and there always focused on external things.

Image Credits: By Jerzy Strzelecki | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 3.0

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By Jerzy Strzelecki | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 3.0

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

What do you think?