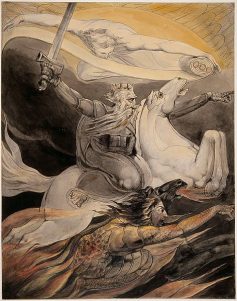

Esoteric Influences in the Work of William Blake

Article By Julian Scott

Many of the world’s great artists were inspired by the perennial, esoteric or occult philosophy and their works of art express timeless truths that continue to speak to our intuitions. The artist and poet William Blake is no exception, but it is not easy to locate him within the esoteric tradition, because he was subject to so many different influences. Kathleen Raine, author of William Blake (published by Thames & Hudson), says that ‘Blake was widely read… in the writings of Plato and Plotinus, Berkeley and the Hermetica, Paracelsus and Fludd, and the mystical theology of Boehme and Swedenborg.’ Elsewhere she writes: ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell [one of Blake’s works] is the fruit of his profound studies of the mystical theology of Boehme, the alchemical writings of Paracelsus, Fludd and Agrippa and his knowledge of the Western Esoteric tradition.’ Blake referred to these and other thinkers as his ‘spiritual friends’ who ‘dined with him’ on ‘the bread of sweet thought and the wine of delight.’

Many of the world’s great artists were inspired by the perennial, esoteric or occult philosophy and their works of art express timeless truths that continue to speak to our intuitions. The artist and poet William Blake is no exception, but it is not easy to locate him within the esoteric tradition, because he was subject to so many different influences. Kathleen Raine, author of William Blake (published by Thames & Hudson), says that ‘Blake was widely read… in the writings of Plato and Plotinus, Berkeley and the Hermetica, Paracelsus and Fludd, and the mystical theology of Boehme and Swedenborg.’ Elsewhere she writes: ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell [one of Blake’s works] is the fruit of his profound studies of the mystical theology of Boehme, the alchemical writings of Paracelsus, Fludd and Agrippa and his knowledge of the Western Esoteric tradition.’ Blake referred to these and other thinkers as his ‘spiritual friends’ who ‘dined with him’ on ‘the bread of sweet thought and the wine of delight.’

In his writings and paintings we can find a number of esoteric themes, which I have listed below in no particular order.

– Eternal Motion, or the One-Life in all things. This is a universal teaching of esoteric philosophy: that Life, or Consciousness, never ceases, neither with death, nor even with the cyclic destruction of the material universe. For Blake this Life, which can be seen in the smallest and humblest of things, such as the worm and the little winged fly, is in its essence joyful. ‘Everything that lives is holy’, he wrote. According to Raine, this is the reason for the apparent weightlessness of Blakes figures – they are expressions of the unimpeded spirit of Life, which is in perpetual motion. According to G.P. Lomazzo, a Renaissance author of a treatise on painting, ‘the greatest grace and life that a painting can have is that it expresses Motion: which the Painters call the Spirite of a picture.’

– Our perception of the world is limited by the constraints of our senses and our mind. In this regard, Blake once wrote these now famous words: “If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern.” The cavern in this case is the body and the narrow chinks are man’s limited senses. But it is not the senses in themselves that are limited, but rather their restriction to the strictly material perceptions. We can also develop our ‘subtle senses’, which would enable us to perceive Life itself, infinitely manifesting in all things. There is a fascinating picture of ‘Aged Ignorance’ clipping the wings of an angel with a pair of scissors. By this Blake was attacking the mechanistic and rationalistic world view prevailing in the 18th century, where reason and mechanistic science, divorced from the spirit of Life, were cutting the human being off from the source of his being, which for Blake was the Imagination.

– The Body and the World are a Cave and a Grave. This is another universal esoteric teaching, which is found particularly in the Orphic tradition of ancient Greece and is echoed in the writings of Plato and Plotinus. Blake was familiar with these through the translations of the 18th century Platonist Thomas Taylor, whom he knew. It does not mean that Blake despised the body or hated the world, but merely believed that the soul is more free and more truly itself when released from its ‘earthly envelope’, or when it can perceive Life beyond the normal restrictions of the senses: ‘Man has no body distinct from his Soul; for that call’d Body is a portion of Soul discerned by the five senses.’ We find the same idea in the Enneads of Plotinus, where he speaks of the ‘embodied soul’, and also in the Indian doctrine of Maya (usually translated as ‘illusion’). Physical nature is regarded as an illusory projection of the Real, which is intangible. Plato expresses the same teaching in his ‘Allegory of the Cave’.

According to Kathleen Raine, Blake’s The Little Girl Lost and The Little Girl Found ‘are a retelling of the Greater and Lesser Mysteries of Eleusis, the descent of Kore into Hades, and the nine mystic nights of the Mother’s search for her child… The poems are based on Taylor’s Dissertation on the Eleusinian and Bacchic Mysteries. Many of Blake’s themes… derive from Thomas Taylor’s writings and translations.’

– Esoteric Christianity. Blake described himself as ‘a worshipper of Christ’, although he never went to Church. According to Raine, he was ‘Swedenborgian in religion’. ‘Blake’s Jesus is so essentially the one God in all, rather than the Jesus of history.’ We can see this in Blake’s painting of the Nativity, where, instead of the usual scene of mother and child, we see a luminous being emerging into the surrounding space from his mother Mary. This is the divine part of every human being, who is in us but is usually suppressed by all sorts of factors, including a materialistic education. Esoteric Christianity sees the events of Christ’s life from a more symbolic point of view: the crucifixion is the inner conflict between the spiritual aspirations of man and his more material desires; and the resurrection and ascension to heaven represent the resolution of this conflict by connecting with the divine part of oneself and being freed from the limitations of matter and the lower mind. All of this can be found in the ‘mythology’ created by Blake and expressed in his paintings and poems.

– The spirit world. As a visionary, Blake ‘saw’ not only the forms of his paintings and received some of his poems by ‘automatic writing’; he would also often perceive subtle beings in nature, such as angels and fairies. We can thus see in Blake’s work the ‘three worlds’ of traditional esoteric teaching: the world of archetypal forms (which he calls the world of Imagination), the world of subtle beings and the physical world itself. As Blake himself wrote: ‘This world of Imagination is Infinite and Eternal, whereas the world of Generation or Vegetation is Finite and Temporal. There exist in that Eternal World the Permanent Realities of Every Thing which we see in this Vegetable Glass of Nature.’

Blake regarded fairies as the living spirits of the vegetable world and once described to a lady a ‘fairy funeral’ which he witnessed one night: “I was walking alone in my garden; there was great stillness among the branches and flowers, and more than common sweetness in the air; I heard a low and pleasant sound, and I knew not whence it came. At last, I saw the broad leaf of a flower move, and underneath I saw a procession of creatures of the size and colour of green and grey grasshoppers, bearing a body laid on a rose-leaf which they buried with songs, and then disappeared. It was a fairy funeral.”

Was he seeing a reality or was it a figment of his imagination? Perhaps he was seeing a reality through his imagination. After all, what is Imagination, and what is Reality? In Blake’s view the two were intimately intertwined. In the poet’s own words: ‘To the Eyes of the Man of Imagination, Nature is Imagination itself… Imagination is Spiritual Sensation.’

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

By www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/gothic-nightmares-fuseli-blake-and-romantic-imagination/gothic-5 | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

What do you think?