The Temples of Ancient Egypt

Article By Agostino Dominici

Introduction

Introduction

The quality of a civilisation’s culture is most visible in its art and more particularly in its architectural accomplishments, for these are usually its most complex and long-lasting forms. It’s hard to conceive of a more awe-inspiring architecture than that found in ancient Egypt. The essence and message of Egyptian architecture remained unaltered throughout the millennia, while its majestic and aesthetic style still manages to convey forgotten psychological and spiritual truths.

The symbolism of the Egyptian temples covers many different aspects and functions. In this article we will first look at the mythological and magical aspects. Then we’ll turn our attention to the study of the different parts of a temple complex, their meaning and symbolism.

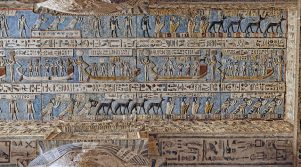

The astronomical ceiling at the Pronaos, Detail of the first stripe east from the centre. The daily voyage of the sun god across the sky. For every one of the twelve hours the sun is depicted in its bark, with a goddess, crowned by a sun disk, standing in adoration before its bow. The lower and upper registers of this ceiling stripe are inhabited by figures, souls and deities who protect and accompanies the sun during its voyage, which progresses from left to right. This picture shows Ra’s voyage during the ninth up to the twelfth, the last hour of the day.

Mythological aspects

The function and purpose of the Egyptian temple is clearly reflected in the teachings found in Egyptian creation myths. These myths relate to the beginning of time when a mound of earth arose from the primeval waters. A bird (symbolising the spiritual element) rested on reeds growing on the mound which became a sacred place.

The temple symbolises this ‘first moment’, with the ceiling representing the heavens, the floor symbolising the mound and the columns the reeds, lotus and papyrus. Each temple is a microcosm of the universe in which each part of its physical structure symbolises an aspect of the origins of the cosmos and the process of cosmic regeneration.

Cosmic cycles of decline and rebirth were part of this temple symbolism, the main function of which was to control the hostile forces of chaos and to maintain harmony, balance and order on Earth. The temple therefore acted as a bridge between the heavenly realm (symbolising order and law) and the earthly realm (symbolising chaotic forces).

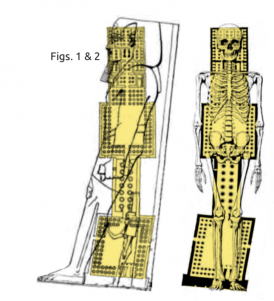

The theme of creation can also be found in the Temple at Luxor. Its proportions and harmonies are symbolically related to the story of the creation of man, his development and his relationship to the universe. Laid out according to the proportions of an idealised male frame (figs. 1 & 2 below), this temple didn’t just reflect the patterns of the physical body; its architecture also revealed the occult and metaphysical anatomy of man.

1. Extract from the book The Temple in Man : Sacred Architecture and the Perfect Man by R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz 1981

Man, in an archetypal sense, is not just a ‘product’ or a ‘scale model’ of the universe, he is its essential embodiment. For this reason, the Temple of Luxor, as a vast stone symbol, also encapsulates the totality of Egyptian ‘universal wisdom’: its science, mathematics, geodesy, geography, medicine, astronomy, astrology, magic, art, etc.

Magical aspects

From a magical perspective, the overall purpose of the temple was to ground associated sidereal influences on Earth. Specific temples were linked to specific star-gods. These magical correspondences were meant to favour a downward pouring of spiritual influences and a constant regeneration of human social culture. The scientific basis of this type of spiritual transmission rested on the correct use of harmonic proportions, magnetism and acoustic resonances. The temple’s architecture was specifically designed to produce its own set of psycho-magnetic effects (as in feng shui) to work upon the subconscious nature of the individual. This architectural feng shui was (and still is) believed to be directly perceived by man’s subtle nature, which also responded (consciously or unconsciously) to the whole temple geometry. In accordance with the aforementioned magical objectives, many temples were deliberately dismantled when their time came to end, and their magical action was disabled by the priests. Some were constructed and demolished according to preordained plans which probably had astrological reasons. Sometimes reliefs and inscriptions that had served their purpose were effaced and nothing new was added.

For our 21st century mentality it’s quite hard to understand the magical side of Egyptian architecture, but if we consider that the Egyptians were very practical people we can perhaps appreciate their intentions better. In fact, if we study some of the later sacred architecture of the West (e.g. medieval cathedrals), we will discover many similarities in knowledge, message and intention.

The constitution of a temple complex.

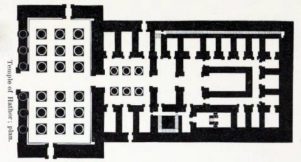

Apart from the temple of Luxor, most of the Egyptian temples were built along a central-axis and followed a rectangular peripheral plan. The plan of the temple followed a threefold structure:

1. Courtyard, 2. Colonnaded hall, 3. Sanctuary (figs. 3 & 4).

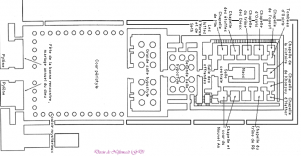

Fig 3. Floor Plan of Temple of Hathor at Dendera

Fig 4. Floor Plan of Edfu Temple

Each contiguous element, as it came closer to the sanctuary, had a higher elevation and a lower roof with decreased illumination and increased ‘sanctity’.

Each gateway or ‘door’ symbolised a transition to a greater state of sacredness and marked the initiatory path. Some of the most important temples followed a 7-gates symbolism (figs. 3 & 4 on the previous page).

Most of the Egyptian temple complexes included the following elements, with their corresponding symbolism:

1) A sacred ‘way’ or road: this represents the pathway which leads man (i.e. the neophyte or initiate) to the temple (in Latin templum is a sacred space) and to the presence of God.

2) The temenos wall: a sacred enclosure wall (fig. 5 opposite) which surrounded the temple complex and marked out the sacred space inside.

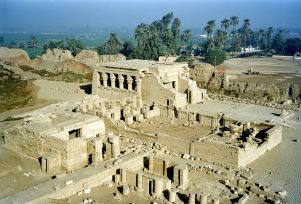

Fig 5. Dendera Temple Complex Arial View

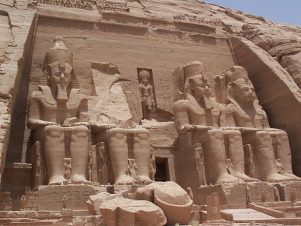

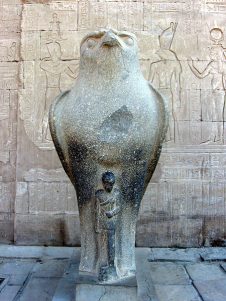

3) A pair of guardian figures: these were often found outside the main gate and were often represented by sphinx-like figures, lions-griffins or giant ‘human’ figures (fig. 6 below). As symbols of protective spiritual beings they held a particular significance and relationship with the temple in question.

Fig 6.1 Two colossal human figures ” guarding” the entrance of Karnak Temple

Fig 6.2 Statue of the “falcon” Horus outside the Edfu Temple

4) A sacred lake: it symbolised (a) the waters of creation (the primordial abyss from which creation arose), (b) ‘the living waters’, nurturer and sustainer of life, (c) the waters of purification.

5) A monumental gateway known as pylons (fig. 7 ): this symbolises the first transitional stage along the sacred path to God. The outer pylons were specifically positioned in such a way as to allow, at a specific time of the year, the rising sun (or a particular star) to direct its rays right through the central axis of the temple and, for an instant, to illumine the innermost sanctuary.

Fig.7

On their mighty walls we find depicted scenes of symbolic battles between the forces of light and darkness. In order to enter the temple and to gain access to the field of knowledge held within, all the ‘external’ and ‘internal’ obstacles had to be overcome. Those images of kings single-handedly smiting their enemies symbolise a sacred battle. The initiate-king is seen subduing his own lower desires and thoughts.

6) The courtyard or outer court: this was specifically linked to various types of sacrifice and offerings. Within their space we find altars used for blood (animal) sacrifices. In general, blood sacrifices were done in the outer court while most of the other offerings were done in the inner parts of the temple.

7) The hypostyle or colonnaded hall: these temple structures (fig. 8 ) are regarded by some authors as symbolising the ‘primordial forest’ or a kind of ‘heavenly garden’. Their peculiar type of illumination system, which follows the camera obscura effect, helped to convey the idea of the separation of the underworld from the true light of the heavenly world above. As found in other mystery rites of antiquity, this type of construction must also have had some theatrical purposes. The columns had various upper capitals shaped in plant forms, perhaps symbolising particular stages of man’s psycho-spiritual unfoldment along the initiatory path.

Fig 8. The Hypostyle Hall, Edfu Temple

8) Astronomical motifs: on the ceilings of various halls we find representations of the heavens with various astronomical scenes. The astronomical modelling is based not on ‘realistic’ but symbolic and spiritual representations. On the roof of many temples we would also find an astronomical observatory (e.g. Dendera Temple. See Fig. 9 opposite). Originally, astronomy (and astrology) was a temple science designed to determine the calendar and the holy days as well as the correct ‘alignment’ and coordination of the temple with the gods (and the sidereal bodies) in heaven.

Fig 9. Built in one corner of the Temple’s roof it is still possible to see the the original Dendera astronomical observatory

9) Sanctuary or holy of holies: this is the innermost chamber where the (symbolical) meeting between man and god took place. Here we would find a shrine (fig. 10 opposite) with the image of the deity to which the temple was dedicated. The statue of the deity would be ritually purified and clothed as if it were a living being (these rites are still performed in Hindu temples). This chamber would be immersed in deep gloom or near-total darkness with only an occasional ray of light falling through an opening in the roof above. It would only be accessed by the hierophant priest or the king-initiate (e.g. the Pharaoh). On the walls of the sanctuary we would also find depictions of the king-initiate standing or sitting next to the tree of life with gods or goddesses writing his name on some ‘sacred fruit’, therefore deifying him and making him immortal (fig. 11, bottom of the page).

Fig 10.

Fig 11.

For the Ancient Egyptians, the main concern was that of maintaining a permanent and direct link between ‘Heaven’ and ‘Earth’. But this could only be done through the agency of man – ‘the fallen god’. Here we are referring, not to any ‘mortal’ man but to an individual who had to have already achieved a direct and conscious link with (his own) divine nature and who could act as the agent of a psycho-spiritual transmission and reception. As suggested by some students of esotericism, originally the spot where we find the above-mentioned statue would have been occupied (on special occasions) by the hierophant of the temple himself.

Image Credits: By Than217 | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD, By Kairoinfo4u | Flickr | CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, By Flickr Commons | CC BY PD, By Néfermaât | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 2.5, By Bernard Gagnon | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 3.0, By a rancid amoeba | Flickr | CC BY-SA 2.0, By ljandersson977 | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD, By Ad Meskens | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 3.0, By Ijanderson977 | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD, By Elias Rovielo | Flickr | CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 , By Terry Feuerborn | Flickr | CC BY-NC 2.0 , By Dennis Jarvis | Flickr | CC BY-SA 2.0

The entity posting this article assumes the responsibility that images used in this article have the requisite permissionsImage References

Feature Image : By Than217 | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD astronomical Ceiling : By Kairoinfo4u | Flickr | CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Fig 1 & 2 : Extract from the book The Temple in Man : Sacred Architecture and the Perfect Man by R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz 1981 Fig 3. : By Flickr Commons | CC BY PD Fig 4: By Néfermaât | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 2.5 Fig 5 : By Bernard Gagnon | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 3.0 Fig 6.1 : By a rancid amoeba | Flickr | CC BY-SA 2.0 Fig 6.2 By Ijanderson977 | Wikimedia Commons | CC Fig 7. By Than217 | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD Fig 8. By Ijanderson977 | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY PD Fig 9. By Elias Rovielo | Flickr | CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Fig 10. By Terry Feuerborn | Flickr | CC BY-NC 2.0 Fig 11. By Dennis Jarvis | Flickr | CC BY-SA 2.0

Permissions required for the publishing of this article have been obtained

What do you think?